Power & money switch polarity

How our oligarchy is giving way to authoritarianism

I was busy reorienting myself the other day. I was reading a good book on the late Roman Empire, Peter Brown’s Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350 — 550 AD. Early on, Brown asks us readers to attempt to put aside how we assume money and power worked together in Rome. Otherwise, the Roman Empire won’t make sense to those of us living in or—Brown must have thought—even long after 2012, when Through the Eye was published. Here’s Brown’s counsel to us:

In Rome there were no persons such as there were in ancient China who could be acclaimed . . . as members of an “untitled nobility.” Wealth and “honors” were made to converge. The one could not be achieved or maintained without the other. For this reason, when approaching wealth in the later empire (as in most other periods of Roman history) we must make a fundamental transition “from a [modern] mental cosmos in which power depends largely on money to one where money depends . . . largely on power.”1

In modern times, power depends on money, but in Rome, money depends on power. Here, as with any effective chiasmus, a contrast in syntax mirrors and strengthens a contrast in semantics: power < money ^ money < power.

Admittedly, President Kennedy achieved a stronger rhetorical effect in his famous chiasmus, “Ask not what your country can do for you–ask what you can do for your country.” But I now think Brown’s chiasmus is more profound.

I didn’t see the chiasmus’s larger importance at first. But as I was thinking through Brown’s suggested reorientation, I realized that I needed to go through a similar reorientation to understand how money and power work not in Ancient Rome but in America’s federal government since the 2024 election.

Up until recently, money made power. Now power makes—or breaks—money.

Power and money have switched polarities.

Above: detail from page 1 of the April 29, 2019 edition of The Washington Post.

Up until the election, if you couldn’t otherwise explain why bad politics persisted, you wouldn’t be far off if you repeated the old adage, “Follow the money.”

Why don’t we have affordable health care as do other developed nations? Follow the money.

Why don’t we ban assault weapons, despite their use in mass killings? Follow the money.

And so on.

Before the reverse polarity, the current was generally running one way: money was making power. Large corporations would back candidates and hire lobbyists to control legislation. They’d get naming rights on major stadiums and arenas. They’d control the research agenda at universities. And so on.

We’re still largely an oligarchy, as Jimmy Carter observed after Citizens United, because the rich still buy power and influence. But this reverse polarity between power and money since the 2024 election shows that we’re becoming something else—an authoritarian regime.

These days, to spot the big, regime-altering moves, don’t bother following the money. Instead, follow the servility. And start with the billionaires and CEOs who got to come in from the cold to witness and celebrate the president’s inaugural.

Witness, for instance, yesterday’s effective shuttering of the Washington Post by its owner, Jeff Bezos, along with the paper’s previously severed relationships with several reporters and writers who weren’t permitted to publish pieces critical of the administration.

Or witness the administration’s use of power to extract large settlement sums from legacy media and to have television shows the president dislikes canceled. Or the administration’s use of power to threaten federal research funding cuts to universities. Or its orders punishing law firms for advocating on behalf of people or causes the president disfavors.

Or witness areas where the administration, to this point anyway, hasn’t met with servility: the administration’s cuts to federal grants to four blue states or the administration’s plans to cut federal funding to sanctuary cities and states.

The administration’s use of power to affect the pocketbooks, and thereby the decisions, of perceived enemies doesn’t stop at the country’s borders. It has used tariffs and the threat of tariffs to influence the internal political decisions of certain countries.

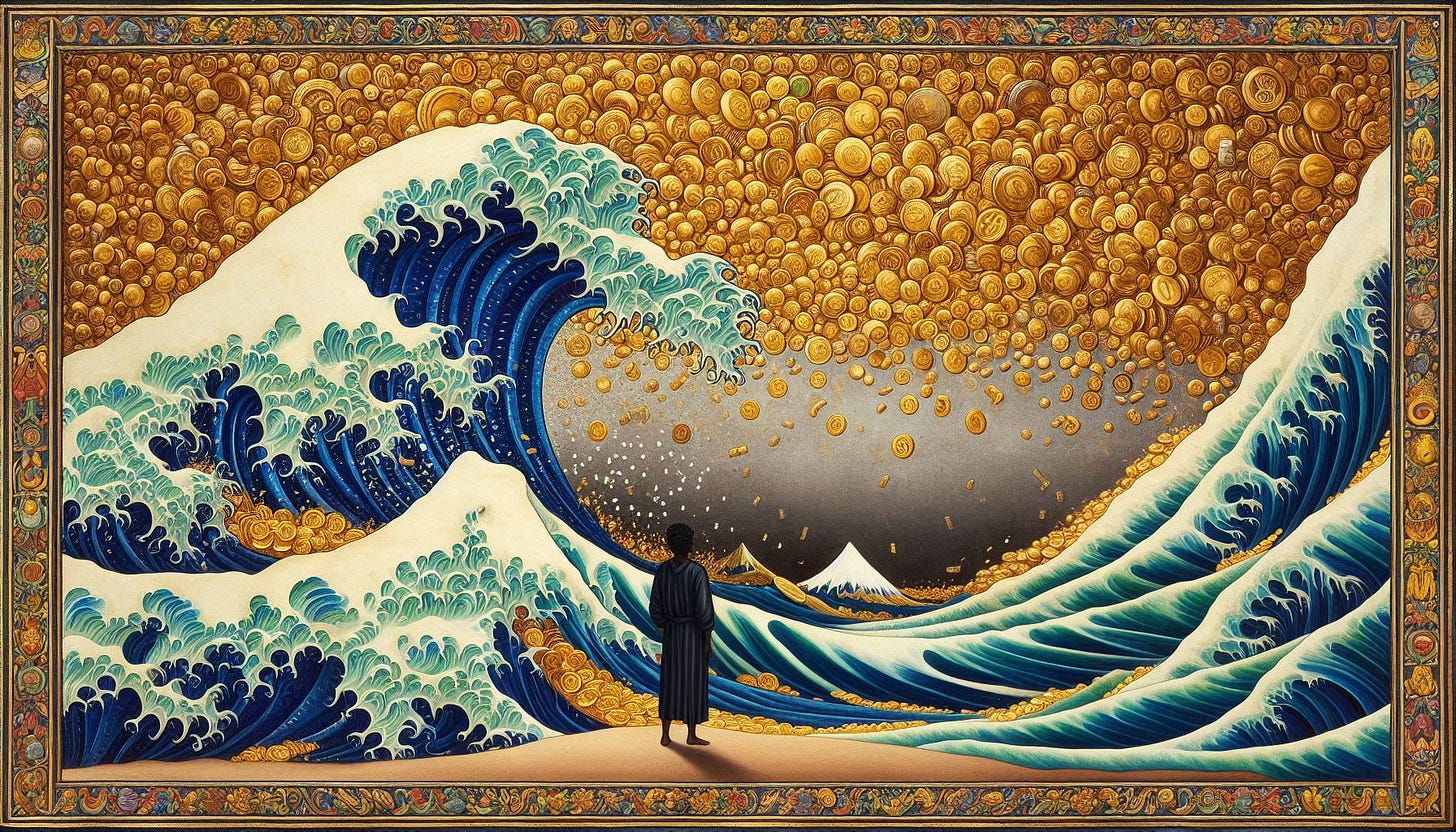

Admittedly, it’s hard for the poor and the middle class to stand on the shore of a great ocean of money and power and discern which way the current is flowing. But once we feel the strong undertow of moneyed obedience, we know that the political current is shifting as surely as global warming is causing ocean currents to shift and in some cases to reverse themselves.

In the case of both politics and oceans, it’s also hard to know exactly what the results will be, but the results likely will be dire. Our new power-makes-money polarity could lead us to ancient Rome, or at least to something like it.

Brown points out that, during the Roman Empire, “most people lived miserable lives,” and their “very bodies remained at the mercy of the Roman state.” Another recent book on Roman history, this one by J. E. Lendon, describes its empire’s “crude application of force (or its insidious threat), reliance on the willing compliance of the subject to authority he acknowledged as legitimate, and the subtle workings of patronage.” There’s also the Roman army, Lendon points out, which not only expanded and defended the empire but also acted against its civilian population.2

You knew all that without my citing these history books. And it’s impossible to know if any of these specifics will come to pass in an American version of authoritarianism. But Rome wasn’t good, and this won’t be good.

Actually, Brown is quoting Lendon’s book, Empire of Honour: The Art of Government in the Roman World, when he mentions the “mental cosmos in which power depends largely on money to one where money depends . . . largely on power.” I like what Lendon says right after his chiasmus, though, to exemplify this reorientation of money and power: “. . . from New York to the Mafia’s Sicily.” All of Rome’s centuries-long “honor,” Lendon suggests, comes down to violence and extortion.3

Classical republicanism, still in vogue 250 years ago when the founders signed the Declaration of Independence, advocated a simple manner of life, one that avoided luxury and excess wealth. Republicans (small “r”) knew that private riches would divert us from active public life. And Jefferson advocated for the daily practice of public life in small communities precisely so we wouldn’t fall for “a Caesar or a Bonaparte.”4

The Bible makes a similar warning about riches, starting with what the King James expresses in its own chiasmus:

. . . supposing that gain is godliness: from such withdraw thyself. But godliness with contentment is great gain.5

Classical republicans similarly understand contentment as gain, as a boon to our public life together.

The writer of 1 Timothy then fleshes out how the love of money hurts us:

. . . for the love of money is a root of all evils, and reaching out for which some have wandered from the Faith and pierced themselves about with many pains.6

Have we not seen over the past several months how quickly the rich have pierced themselves, how easily they have been manipulated by power?

Are they free?

I don’t think the relationship between public freedom and money can be expressed any better than how Janis Joplin has sung it: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.”7

A lot of the smart money had a lot to lose, and still does. A lot of it has surrendered to power’s newly minted willingness to extort.

And like the rich, soon we also may have to choose: our money or our public life.

The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the earlier manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Peter Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350 - 550 AD, Eight printing and first paperback printing (Princeton Univ. Press, 2014), 5.

J. E. Lendon, Empire of Honour: The Art of Government in the Roman World, Reprinted (Oxford University Press, 2005), 3-4.

Lendon, 30.

Jefferson, Letter to Joseph C. Cabell (02.02.1816), 205.

1 Timothy 6:5-6 KJV.

1 Timothy 6:8, 10, Hart, New Testament, 421-22.

A line from “Me and Bobby McGee,” written by Kris Kristofferson.

Bryce, a wonderful review, from Rome to SCOTUS to Elon.

I think there is a bit too much love for the concept of chiasmus, however. The callow caudillo understands power is maintained with violence — against bodies, against language — but also as a means to money. The orange family has reportedly made over $1b in a year in power. Centering on chiasmus in this contest feels a bit like chicken or the egg. Rich b/c of power or powerful b/c rich? In these days of the Epstein Class, I think the answer is simply, Yes.

You show how money and power have changed roles, using examples from Rome, scripture, and other historical events. The use of chiasmus makes the argument clear and avoids slogans. Changing from “follow the money” to “follow the servility” helps explain this shift in thinking. The last question about freedom encourages readers to make a conscious choice rather than simply seek comfort. - Thanks for pulling together... a lot!