Theodicy and the Odyssey

God to Job: We're in a political fight of mythic proportions

Homer's Odysseus and the Hebrew God have a lot in common. For starters, they're both kings intent on returning to their kingdoms. Odysseus's return to his kingdom in Ithica, chronicled in the Odyssey, offers us insights into "thy kingdom come," the Bible's similar theme of God's return to his reign on earth.1 Those insights may help us develop the contours of our own political destinies in these dark times.

In this exploration, I won’t overlook significant differences between these epic heroes, Odysseus and God. Odysseus cheats on his wife and accounts for his infidelity by claiming that his lovers are literally irresistible goddesses. Odysseus’s curiosity, arrogance and misjudgment contribute to the deaths of many of his devoted fellow travelers, though their own flaws often did them in, too. Odysseus is heroic, sure, but he comes across as rather arbitrary and callous about the fate and feelings of others. God, by contrast, is God.

But God seems arbitrary and callous, too, in the first two chapters of Job. Our journey toward political destiny starts in Job, moves to Genesis's creation story, to Israel's exodus, and finally back to Job’s theodicy. With Homer’s Odyssey as our guide at pivotal points, we'll discover how the Bible's adopted prehistoric myths, so prominent in Job, help to fuel the Bible’s historical narrative in imperial contexts as well as our spiritual and political work in those contexts today.

Above: Incoming Tide, Scarboro Maine by Winslow Homer

The action in Job starts when, to test Job’s devotion, God permits the Adversary to cause the death of Job's children and most of his servants and the loss of his livestock. Even less than Odysseus's shipmates, Job doesn't deserve this: he is, the book's incipit tells us, "blameless and upright."2

How could God be so arbitrary as to permit such evil? Job's narrative opening seems to anticipate a dialog among Job and his three friends about theodicy, which the dictionary defines as "the vindication of divine goodness and providence in view of the existence of evil."3 Theodicy attempts to justify God despite the existence of evil in the world he created. In popular works, theodicy is often reduced to addressing why bad things happen to good people, and this anthropocentric and individualistic reduction certainly applies to Job, too.

For a while, Job's dialog does focus on theodicy, or at least on Job's friends' flawed theodicy. His friends' theodicy is essentially syllogistic: bad things don't happen to good people; bad things happened to you; therefore, you aren’t a good person. The Job poet's mostly unsympathetic rendering of Job's friends' cruel theodicy offers a negative critique of ancient wisdom, Professor Raymond P. Scheindlin points out. Ancient wisdom places suffering in "a predictable universal pattern," Scheindlin says, and posits "an exact correlation between behavior and outcome."4 Faced, then, with Job's epic suffering and compelled to defend their ancient-wisdom theodicy, Job's friends eventually take off the gloves and accuse him falsely of many specific acts of injustice.5

Job, meanwhile, defends himself. He longs to take God to court to learn of God's charges against him and to litigate their differences.

Near the book's end, Job gets his wish, sort of. God appears to Job and his friends from a storm, much as Odysseus appears to King Alcinous and his Phaecian subjects from a storm. In the latter appearance, Odysseus tells Alcinous of how Poseidon, the god of the sea and storms, destroys Odysseus’s raft and tries to smash him, too, against Phaecia’s rocks. The next day, at Alcinous's banquet in Odysseus's honor, Odysseus tells the king and his guests of more adventures on the chaotic seas. He speaks of how Zeus and Poseidon cause strong winds and storms to blow his ship to the dangerous Cicones, Lotus-Eaters, and the sun god Helius.

In Job, God tells of much the same thing. God gives his hosts two long talks that, taken as a whole, have waters as their chief setting. However, while Odysseus makes explicit references to his struggles with the sea, God makes mostly allusions to his own struggles with the sea.

God starts his first speech to Job by asking Job where he was when God founded the earth, and he asks him if he had "ever reached the depths of the sea / and walked around there, exploring the abyss?"6

God is there at the beginning, of course. And God battles the seas back then, just as Odysseus battles them much later. In the Bible, the sea often "represents chaos and rebellion; it is the untamed part of creation," Professor Mitchell G. Reddish says.7 The sea, Professor Robert Luyster points out, "was felt as a threat to the established cosmic and social order."8

So before God creates heaven and earth, he must defeat the waters of chaos. He does so in the first verses of Genesis with his breath—his wind—as it sweeps over the waters and divides them, Luyster says:

. . . Yahweh, even before undertaking any direct, creative action, is present and exercising a restraining influence upon the surging, watery chaos. The wind of Yahweh is the ultimate expression of his power and supreme cosmic authority.9

This battle between God’s wind and chaos’s surging water is political. Just as Odysseus's eventual victory over the sea precedes his return as king of Ithaca, so also, Luyster says, "Yahweh's ability to contain and dominate the cosmic waters, the forces of chaos is the absolute prerequisite and surest sign of his divine kingship."10 Here are two of several biblical texts that relate God’s victory over the sea to God’s political standing on earth:

Lord God of Hosts, who is like you? Your strength and faithfulness, Lord, are all around you. You rule the raging of the sea, calming the turmoil of its waves. You crushed and slew the monster Rahab and scattered your enemies with your strong arm.11

The voice of the Lord echoes over the waters; the God of glory thunders; the Lord thunders over the mighty waters, the voice of the Lord in power, the voice of the Lord in majesty. . . . The Lord is king above the flood, the Lord has taken his royal seat as king for ever.12

Once God's victory over chaos makes him the earth's lord, his creation amounts to both the proof and the glory of his lordship.13

When alluding to these victories in Job, though, God moves in reverse order, starting with creation before moving back to his battle with chaos. God spends the better part of his first speech to Job talking about several creatures, all of them identifiable and found on the lands or in the skies of the natural world. But after an interlude consisting of Job's repentance, God takes up his second speech and spends the greater part of it talking about only two creatures, both of them sea monsters—or in the context of Job, water monsters.

God seems more preoccupied with the subjects of his water-monster speech than with the subjects of his creation speech, Scheindlin observes:

. . . while the descriptions in the first speech were enthusiastic depictions of nature designed to call attention to God's power and providence, the descriptions in the second speech are occupied more with the character of the animals themselves . . .14

God's engrossed and less-than-celebratory tone with respect to the water monsters suggests that creation—and God's rule that creation represents—is still threatened by the water monsters. Indeed, Professor L. Michael Morales suggests that the elusive "'center' for biblical theology" could be God's continuing struggle against one of these two monsters. Morales asks us to picture the Bible's overall plot as a knight (think Don Quixote) raising his lance "against Leviathan, the chaos-dragon of the sea."15

In other words, Morales suggests that, with Leviathan, the more fearsome of Job’s water monsters, we have reached the mythic heart inside the Bible’s account of God’s past, present, and future action—from heaven and earth’s creation to the present and until God’s kingdom of heaven fully comes to earth.

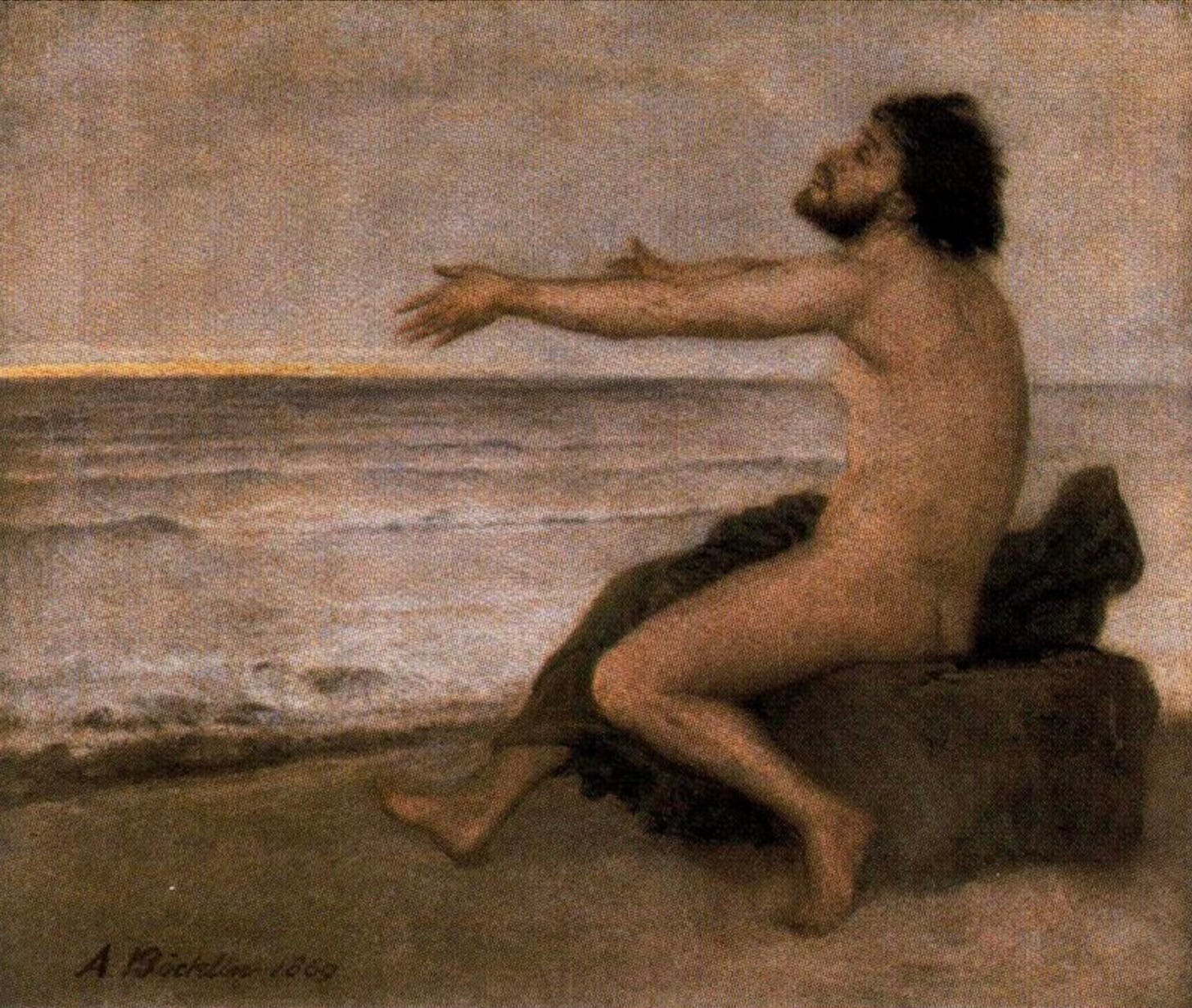

Above: Odysseus by the Sea by Arnold Böcklin

So what do these two monsters in Job, particularly Leviathan, look like?

The two monsters "appear to be partly mythological creatures, or, if real, still retain some supernatural overtones from the mythology of the earlier stages of Israelite religion," Scheindlin says.16 The anatomy and powers of Job's first water monster, Behemoth, amount to "a mythological heightening" of the Egyptian hippopotamus, Professor Robert Alter says.17 Behemoth, which is the Hebrew word for “animal”18 or “beast,”19 acts rather like a cosmic hippo: he can, for instance, drink entire rivers.20

The orientation of each monster, though, is different: Behemoth's "impassivity and tranquility," as Scheindlin describes the creature's temperament, offers a foil to the "fearsome dangerousness" of the second water creature, Leviathan.21

Odysseus likewise faces two sea monsters, Charybdis and Scylla, and he must sail between them. Charybdis, like Behemoth, is a guzzler. Whirlpool-like, "divine Charybdis sucks black water down. Three times a day she spurts it up; three times she glugs it down."22

Just as Charybdis resembles Behemoth, so also Scylla resembles Leviathan. Scylla has six heads, "six long necks with a gruesome head on each, and in each face three rows of crowded teeth, pregnant with death." The Bible's Leviathan also has several heads. The psalmist describes Leviathan as having more than one head.23 Revelation, for its part, describes "a great red dragon having seven heads and ten horns,"24 and one of the inspirations for John's dragon is Leviathan, Reddish says, recounting Leviathan in the Bible’s pages as "a mythological sea monster, usually in the form of a serpent or dragon."25

Leviathan comes from an early, mythological "stage of Israelite religion," Scheindlin says.26 However, unlike the modern West's account of its own epistemological trajectory, the Bible never distances itself from its mythological stage. Leviathan, and allusions to the prehistoric myth surrounding God's victory over Leviathan and the sea, return again and again in the Bible. (See, for instance, Job 3:8; 9:13; 40:25; Psalm 74:14; 89:10; 104:26; Isaiah 27:1; 51:9, some of which refer to Leviathan as “Rahab.”)

Yahweh defeats Leviathan before he begins creation, but this prehistoric battle signals a much longer war. Behemoth and Leviathan return in the New Testament in the form of Revelation's two beasts, Reddish says:

. . . the first beast is an adaptation of the ancient mythological sea monster Leviathan, [and] the second beast is modeled after another primeval monster—Behemoth, the monster on the land. Leviathan and Behemoth were primordial monsters who would be killed in the end time when the messiah comes.27

The Bible never grows out of the mythological "stage of Israelite religion" because, despite God's victory over the seas before Genesis's six days of creation, the chaos that the myth accounts for won't finally be defeated until the end of the age.

Isaiah and Revelation, books that examine the end of the age, have it in for the sea and sea monsters. Isaiah 65:17-25 explores the justice and equality of when God creates “new heavens and a new earth,” and Isaiah 27:1 tells of how

In that day the Lord with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea.28

Yahweh here defeats Leviathan for the last time at the end of time, as Scheindlin points out:

. . . looking ahead to the end of time, Isaiah 27:1 figures Yahweh’s ultimate victory over his enemies as a renewal of these primeval victories, Leviathan being explicitly named as one of the antagonists.

Similar to Isaiah’s account of the end, Revelation’s announcement of a new heaven and earth simultaneously announces the end of the sea: “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth passed away, and there is no longer any sea.”29 Reddish points out that this verse announces the final end of chaos:

In ancient Israelite mythology, the sea was the place where the monstrous power of chaos lived, Leviathan or Rahab . . . In the old order, the sea was still present, both on the earth and even in heaven. In the new heaven and earth, no place exists for the sea because chaos, rebellion, and evil have all been eliminated.30

What, then, is chaos? Chaos in the Bible is essentially political. Before creation, it attempts to keep God from becoming king. It still challenges God's sole earthly sovereignty, expressed through a just and public-oriented polity, with its own oppressive and unjust sovereignty. Chaos in the Bible is not anarchy, then, but its opposite—authoritarianism.31 And the opposite of chaos isn’t control—something at which authoritarians excel32—but complexity, to which God’s creation gives witness.

Sometimes chaos appears in the Bible's pages as particular empires. Most scholars of Revelation agree that Revelation’s version of Leviathan (the beast from the sea) represents the Roman Empire, and Revelation’s version of Behemoth (the best from the land), disguised as a lamb,33 are those forces in Asia Minor that support Rome’s imperial cult.34

Before Leviathan appears as Rome, Leviathan appears as Egypt. A number of texts in the Hebrew Bible, Professor Terence E. Fretheim points out, "identify the chaos monster with Pharaoh/Egypt," another empire. (These texts include Ezekiel 29:3-5; 32:2-8; Psalm 87:4; and Isaiah 30:7.) In these texts, "Egypt is considered a historical embodiment of the forces of chaos, threatening to undo God's creation."35

Egypt holds a special place in the Bible’s nexus of chaos and empire. Israel's exodus from empire's bondage through the Red Sea amounts to a political exegesis of the Bible's first two verses. This exegesis starts with Exodus’s mythic diction in one of its accounts of Israel’s exodus from Egypt. Exodus uses the creation language of Genesis to connect God's original victory over chaos in Genesis with his victory over Egypt and pharaoh in Exodus:

At the blast of your anger the sea piled up; the water stood up like a bank; out at sea the great deep congealed. The enemy boasted, “I shall pursue, I shall overtake; I shall divide the spoil, I shall glut my appetite on them; I shall draw my sword, I shall rid myself of them.” You blew with your blast; the sea covered them; they sank like lead in the swelling waves.36

The similar diction matches the similar action: At the Red Sea, God's wind again separates the waters from the waters as it does in Genesis, but instead of creating the first dry land, God's wind allows Israel to escape political bondage on dry land. Professor Richard J. Clifford points out this interplay between God's victories in Genesis and Exodus: "Here the victory is not against Sea but against Pharaoh's troops at the sea . . ."37

God's victory against chaos in Genesis leads to the creation of heaven and earth, but God's victory against chaos in Exodus leads to the creation of a people. Rabbi Bernard Och puts the connection between God's victories in Genesis 1 and Exodus 14-15 this way:

Israel is the historical counterpart and completion to cosmic creation. The Creator God now appears as the Redeemer God whose creative power extends into history, not for the purpose of redoing cosmic creation, but for the purpose of creating a people who will mediate the presence of God to the world.38

In both victories and acts of creation, God moves from myth to history, and we participate in this history as co-creators with God.

All of these theologians explicitly connect myth, particularly myth involving Leviathan and the sea, with spiritual and political destiny.

But during his speeches in Job, God never puts Behemoth or Leviathan in such explicitly theological or historical terms. Instead, God sticks with myth. He sticks with merely describing Behemoth and Leviathan and their proclivities and powers. He never even formally concludes; God's description of Leviathan leads to no peroration or sense of closure. God's rhetorical failure to switch genres from myth to history or even to argument is perhaps why Scheindlin feels, as most of us might, that "something is missing" at the end of God's speeches to Job and his friends.39

What's missing, from the standpoint of Job's plot and ostensible theme, may be theodicy. God’s description of creation and then of sea monsters never gets around to answering Job's question, “Why do I suffer?”

But an adequate answer—an adequate theodicy—may not exist. If it does, I'm not sure it can be derived from the Bible without some violence to the Bible's overall religious and political plot, which resembles Homer’s Odyssey more than, say, a Platonic dialogue.

Theodicy, after all, assumes that God, by his word, created heaven and earth, including (however indirectly) the earth's injustice, from nothing. But that's not Genesis. The Bible doesn't account for a creation ex nihilo, as Luyster points out:

The cosmos pre-exists; it needs only to be revealed, organized, and defended against further reductions to a chaotic state.40

In other words, the Bible starts as the Odyssey starts—in medias res. Odysseus is in trouble, and the gods plot to help him. In the Bible, the cosmos is in chaos and darkness, and God sets out, as Luyster suggests, to reveal, organize, and defend the hidden cosmos.

But for most Bible readers today, what’s hidden isn’t cosmos but chaos. The King James Version and its progeny obscure the world’s preexisting chaos with their forthright openings, such as “In the beginning, God created . . .” One can see the Bible’s in medias res opening, though, in more recent and more accurate English translations of the Bible’s opening syntax. Robert Alter’s opening, for instance, subordinates God’s creation to the chaotic setting:

When God began to create the heaven and the earth, and the earth then was welter and waste and darkness over the deep and God’s breath hovering over the waters, God said . . .41

One can more easily see the drama between preexisting chaos and eventual creation also in the Bible’s other accounts of creation, such as Psalm 104:5-9 and Psalm 74:13-15. Scheindlin summarizes the drama found in Psalm 74:

Looking back to the moment of creation, Psalms 74:13-15 describes Yahweh as the victor over the chaotic forces represented by the sea and the sea monsters, including Leviathan.42

With the creation of heaven and earth represented as a continuing battle against political chaos and not as a magician’s act of turning nothing into something, theodicy takes a back seat to plot and conflict. Or maybe theodicy doesn’t make the trip at all.

But if anyone deserves an adequate theodicy, it’s Job. Instead, he’s redirected to the ongoing cosmic battle between creation and chaos. Why?

In Job, theodicy and myth present a paradox. Job is blameless, but he is also implicated. Job not only suffers from chaos but participates in it as well. Granted, Job doesn't curse God despite his wife's urging,43 but in response to his suffering, Job himself invokes Leviathan, hoping that the entire cosmos would return to this chaos: "May those curse it who curse the day, Who are prepared to disturb Leviathan."44 Scheindlin points out that, "[b]y invoking those who know how to stir up Leviathan, Job is actually asking for the overthrow of the order of the cosmos."45

From the standpoint of theodicy, Job is blameless—a perfect test case. But in the context of the cosmic battle, perhaps Job hasn’t yet suited up. One gets this sense from God’s first words to Job:

Who is this who darkens the divine plan / By words without knowledge? / Now tighten the belt on your waist like a man . . .46

Job, we are to understand, “darkens the divine plan” by inviting chaos to destroy creation.47

But to suit up—to “tighten the belt on your waist like a man”—doesn’t mean to take on Leviathan alone, even if one is “blameless and upright.” In fact, God speaks of Leviathan partly in terms of an imagined interaction between Job and Leviathan:

If ever you lift your hand against him, think of the struggle that awaits you, and stop! Anyone who tackles him has no hope of success, but is overcome at the very sight of him. How fierce he is when roused! Who is able to stand up to him?48

Speaking not only to Job but to all of us, God in his description of Leviathan suggests that people are unable on their own to control or fight the chaos of empire when it returns.

And, of course, it has returned.

The contrast in Job between theodicy and myth—between the speeches of Job and his friends, on the one hand, and the final speech of God, on the other—presents more than a paradox. It presents dueling orientations to life and to the spiritual and political forces that would destroy life.

Philosophy alone won’t do. Compartmentalizing spiritual matters away from political ones won’t do. God’s interaction with Job and his rational friends brings to mind Hamlet’s interaction with his rational friends, Horatio and Marcellus. While listening to the ghost of his father, the murdered king, howling beneath them, Hamlet can only hint at a wider cosmos: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”49

God hints, too. Mythical language, from Genesis to Revelation, is never explicitly translated into the historical moment. That's our job—not only with our words, as I am attempting to do here, but also with our presence and our action. Most of all, our translation involves our responsiveness to the Spirit, who is yet blowing on the waters and drawing together God's created people “of every tribe and language, nation and race,”50 a people pictured as coming out of the Red Sea together.

Above: Passage of the Jews through the Red Sea by Ivan Aivazovsky. The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Professor Moshe Weinfeld points out that God’s “rest” on the seventh day of creation is in the sense of making the earth his resting-place, similar to David’s Temple becoming God’s resting place in Psalm 132. Weinfeld, “Sabbath, Temple,” 150.

Job 1:1 REB.

Oxford American Dictionary, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), s.v. “theodicy.”

Raymond P. Scheindlin, ed., The Book of Job (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), 21.

See, for instance, a portion of Eliphaz’s last speech in Job 22:4-10, which begins with “Does he arraign you for your piety—is it on this count he brings you to trial? No: it is because your wickedness is so great, and your depravity passes all bounds.” Job 22:4-5 REB.

Job 38:16 (Scheindlin, 144).

Mitchell Glenn Reddish, Revelation, Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary (Macon, Ga: Smyth & Helwys Pub, 2001), 401.

Luyster, “Wind and Water,” 249.

Luyster, 257. The concepts of Yahweh's wind and voice (and his word) "faded into each other," and "both derive from the breath or rûah," Luyster says. Luyster, 256.

Luyster, 250.

Psalm 89:8-10. Rahab is another name for the sea monster Leviathan (see below).

Psalm 29:3-4, 10 REB. For more such verses, see Luyster's article "Wind and Water: Cosmogonic Symbolism in the Old Testament."

See, for instance, Rev. 4:11 REB: "You are worthy, O Lord our God, to receive glory and honour and power, because you created all things . . ."

Scheindlin, 220.

L. Michael Morales, “Editor’s Preface: Tilting Toward a P-Centered Theology,” in Cult and Cosmos: Tilting toward a Temple-Centered Theology, ed. L. Michael Morales, Biblical Tools and Studies, volume 18 (Leuven ; Paris ; Walpole, MA: Peeters, 2014), 3. Italics in the original.

Scheindlin, 220.

Alter, Hebrew Bible, Vol. 3, 572n15.

Scheindlin, 219.

Alter, Hebrew Bible, Vol. 3, 572n15.

Job 40:23.

Scheindlin, 220.

Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Emily R. Wilson, First edition (New York London: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2018), 304 (Book 12, Lines 104-106).

Psalm 74:14.

Revelation 12:3 NNAS.

Reddish, 234.

Scheindlin, 220.

Reddish, 257.

Isaiah 27:1 KJV.

Revelation 21:1 NNAS.

Reddish, 401.

Thomas Hobbes used “Leviathan” to describe an authoritarian who would prevent chaos. Compare Hobbes’s understanding with the Bible’s understanding of Leviathan as the dark forces behind an authoritarian—dark forces that would foster chaos, not prevent it.

Boomers raised on the T.V. series Get Smart, which pitted Maxwell Smart’s “Control” against the evil “Chaos,” will need to reorient their theopolitics.

Revelation 13:11.

Michael J. Gorman, Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness: Following the Lamb into the New Creation ([S.l.]: Cascade Books, 2011), 167.

Fretheim, “Reclamation of Creation,” 320. Professor Herbert G. May makes the same connection through an exegesis of Ezekiel 32, “in an oracle in which Pharaoh of Egypt is described as ‘like a dragon in the seas’ (vs. 2). . . . The king and land of Egypt are a manifestation of cosmic intransigent elements.” May, “Some Cosmic Connotations,” 265.

Exodus 15:8-10 REB.

Clifford, “Temple and the Holy Mountain,” 92. Italics in the original.

Och, “Creation and Redemption,” 340. Clifford agrees: “The defeat of Pharaoh, who had prevented the emergence of Israel as a people, could be interpreted as the defeat of chaos, while Yahweh’s victory was the creation of a people.” Clifford, 92-93.

Scheindlin, 220.

Luyster, 256. Rabbi Everett Fox makes the same point: “Gen. 1 describes God’s bringing order out of chaos, not creation from nothingness.” Fox, Five Books of Moses, 13n2.

Genesis 1:1-2 (Alter, Five Books of Moses, 11). See also the subordinate clause that constitutes Genesis 1:1 in The Jewish Study Bible and the subordinate phrases and clauses that constitute Genesis 1:1-2 in Rabbi Everett Fox's The Five Books of Moses.

Scheindlin, 165.

Job 2:9-10.

Job 3:8 NNAS.

Scheindlin, 165. Walter Brueggemann and Tod Linafelt agree: "Job 3 then becomes a poetic dismantling of God's creation, as Job calls on darkness to reclaim created light and even call up God's old adversary the anticreation chaos monster Leviathan (v. 8)." Brueggemann and Linafelt, Introduction to the Old Testament, 323.

Job 38:2-3 NNAS.

God’s opening rebuke of Job’s wish for created order’s overthrow seems to explain the order of God’s two speeches. In his first speech, God speaks of how he places the sea in bounds ("Thus far may you come but no farther” — Job 38:8-11 REB), then he takes Job through the glories of creation itself. Almost every animal and natural phenomenon is introduced with a rhetorical question, asking whether Job and not God created, equipped, or instructed it (e.g., “Do you give the horse his strength?” Job 39:19 REB)—that is, whether Job (and the chaos Job champions in his distress) or God is the earth’s sovereign. In his second speech, after Job repents, God returns to the prehistoric struggle, now ongoing, in the form of Behemoth and Leviathan, perhaps as a means of enlisting Job’s participation in it.

Job 41:8-10 REB.

Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1.5.185-88.

Revelation 5:9 REB.

A fascinating comparison of these two texts, which might remind the reader of Erich Auerbach's contrast between Hebrew scripture and Homeric narration in his Mimesis. But your reflections on the primal chaos take us to a different place!

This essay doesn’t just draw clever parallels. It unpacks how the Odyssey and the Book of Job confront the same hard questions about power, suffering, and the meaning of return. Their trials are not just a test, but they also give them a kind of moral authority that makes their return matter. That's what we all may really long for: not just justice, but the return of someone who’s suffered, wandered, and come back changed—a figure formed less by victory than by the ordeals that earn our trust. Thanks again, Bryce!