The victory processions of Napoleon, Hitler, Titus & Christ

Fleeing the Gestapo, Walter Benjamin asserts our "weak Messianic power" against tyranny

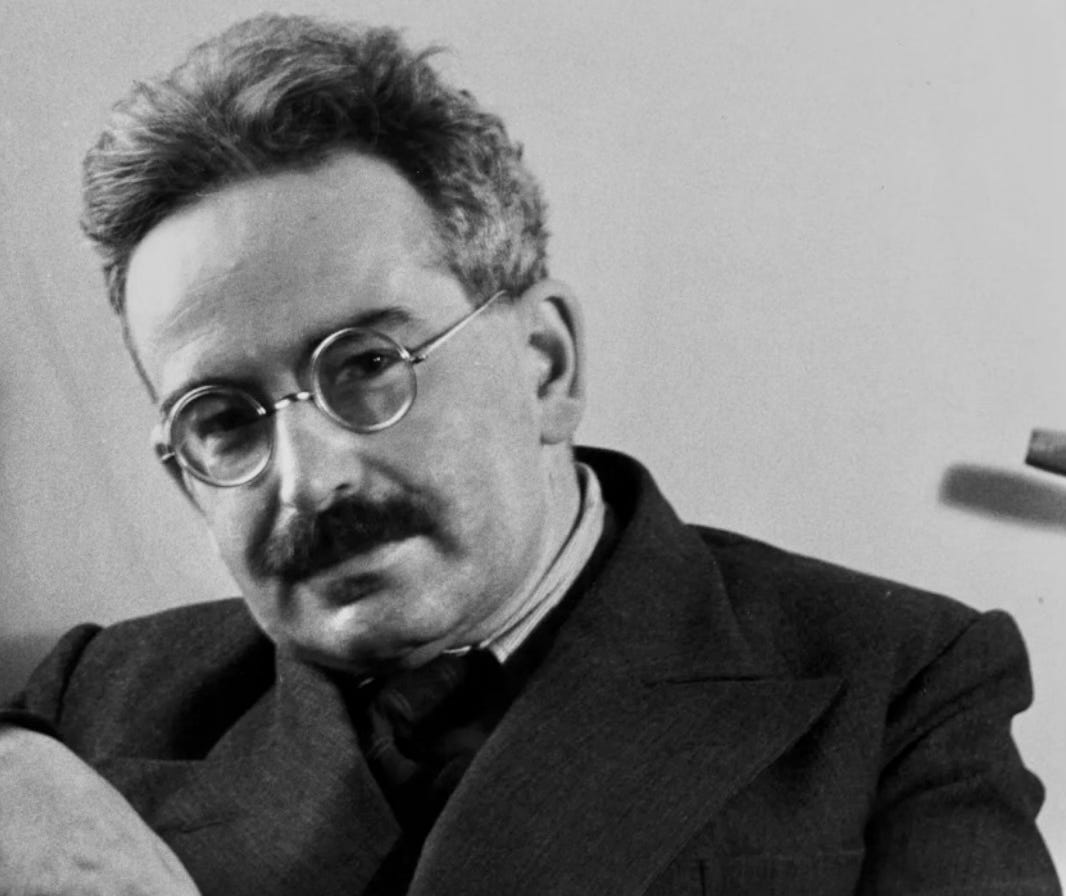

I. Walter Benjamin’s style, substance, & tragedy

The footage still shocks. In June, 1940, after capturing two million French soldiers, the Nazis paraded their tanks down the Champs-Élysées and around the Arc de Triomphe.

Some German-Jewish intellectuals exiled in France barely escaped.1 Hannah Arendt, for instance, landed in Lisbon. But her friend and fellow theorist Walter Benjamin wasn't so lucky. As the Nazis closed in, he committed suicide in the Pyrenees. Spanish officials hours earlier had refused him and his friends entry.

A month or two before France's surrender, Benjamin finished what Arendt's biographer Elisabeth Young-Bruehl calls his "last testament," a collection of eighteen theses on history and Messianic hope.2 Benjamin slipped it to Arendt and her husband for safekeeping. Twenty-eight years later, Arendt edited Illuminations, a book of Benjamin's essays and other short pieces that concludes suitably with his "Theses on the Philosophy of History."

Above: relief from the south inner panel of the Arch of Titus depicting the victory procession to Rome after Jerusalem’s destruction in 71 C.E. Photo used by permission courtesy of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World.

"Theses" brings together "political, historical, and theological motifs in an original way," as two of Benjamin's biographers put it.3 Consider this example of politics, history, and theology working together in a passage from Thesis 8:

One reason why Fascism has a chance is that in the name of progress its opponents treat it as an historical norm. The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are "still" possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge—unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which gives rise to it is untenable.4

I'll highlight one way politics, history, and theology work together here. Benjamin challenges civilization's philosophy of history, which assumes a general progression from barbarism to civilization. Such a linear, sanguine, and ultimately enervating philosophy struggles to find Fascism's place on its continuum. The religious reference to "the beginning of knowledge," which the Bible famously equates with the fear of God,5 suggests that, by contrast, civilization is inadequate to address Fascism's rise.

The thesis ends with a ray of hope, but the hope is unexplained. How could the shock of Fascism lead us to reject our view of history? What view of history is adequate to the moment? No explanation immediately ensues.

Ultimately, though, the theses' original combination of politics, history, and theology will help us address the rise of tyranny around the world in our own era. Benjamin's "Theses" leads us to a sense of the present in which to act. But hinting here at my own thesis gets ahead of my introduction to Benjamin's writing.

Susan Sontag thinks that Benjamin's "intellectual perspectives are vertiginous."6 Benjamin's style matches his intellectual substance: part of the vertigo we readers experience comes from his fragmentary means of presenting those perspectives. Michael P. Steinberg describes Benjamin's approach as "a prismatic renegotiation." We’re used to direct light, but Benjamin leaves a spectrum of refracted thoughts for us to work with. To struggle with Benjamin's fragments, Steinberg suggests, is "to reempower [Benjamin's texts] by restoring the existential context of spiritual and physical survival."7

When we read Benjamin well, Steinberg suggests, we're participating with Benjamin in “spiritual and physical survival.” Reading Benjamin becomes what reading can be—an intellectual act of mutual aid. We discover ourselves in community through not only picking up Benjamin’s pieces but also sharing them. Book discussions become public spaces.

At times, though, I don't know where to begin with Benjamin. His startling, allusive, and lapidary prose brings me joy, but beneath his singular style I feel a complicated philosophical engine that makes it go. Benjamin is original under the hood, too, and he's always tinkering. In the "Theses" alone, it's easy to spot Nietzsche, Marx, and Jewish mysticism, but despite his evident use of these traditions, one feels that neither a Nietzschean nor a Marxist nor a Kabbalist would be happy with Benjamin's tinkering.

A reader would find also that Benjamin's philosophy and his critical perspective may not be consistent at any two points of his career as a critic, a philosopher, a historian, a newspaper contributor, and according to many of his acquaintances (as per his biographers), "a kind of seer."8

Benjamin was certainly a kind of seeker. His close friend Gershom Scholem, a Zionist, found him to be both strident and tentative:

Later I made a detailed, critical study of these conversations [with Benjamin early in their friendship], since, as I wrote at the time, “if I really want to go along with Benjamin, I shall have to make enormous revisions. My Zionism is too deeply anchored in me to be shaken by anything.” I also made this notation: “The word irgendwie [somehow] is the stamp of a point of view in the making. I never have heard anyone use this word more frequently than Benjamin.”9

One gets a sense "of a point of view in the making" from the ending of Thesis 8, quoted above. Benjamin writing is polished, but it also never gets beyond thinking out loud. He seems to insist on his writing style itself as a heuristic. One must stop and start to get at something adequately. Political, religious, and historical enlightenment, his prose seems to say, is a journey. As a Benjamin reader, I somehow share Scholem's joy to be on the journey with Benjamin. And as I read Benjamin, I also share Scholem’s sense that "I shall have to make enormous revisions."

The friends, genres, and intellectual schools that informed Benjamin's thinking help me with some of the engine trouble caused by Benjamin's originality. His friends, in fact, seem to fight over him, often disagreeing with one another when I'm compelled to widen my circle to understand him better.10

The fights are often personal because, despite his saturnine personality, Benjamin had a gift for deep friendships. Long after Benjamin's death, Scholem defended his understanding of Benjamin as an "essentially religious" personality, as Lee Siegel puts it.11 When Marxists laid claim to Benjamin in the 1960s, Scholem responded in 1975 not with a treatise but with a memoir—Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship.

While loyalty to our versions of Benjamin brings conflict, our loyalty to the full and ultimately unknowable Benjamin is greater. After Benjamin died, for instance, Scholem and another of Benjamin's close friends, Theodor Adorno, who was a student of Marxism, put aside their differing philosophical connections with Benjamin long enough to edit his correspondence.12

The best summary of a full and unknowable Benjamin, I think, comes from Scholem. In his last months on earth, Benjamin read a manuscript of Scholem's book Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism,13 but Benjamin never got to read the dedication published with the book after his death:

TO THE MEMORY OF

WALTER BENJAMIN

(1892–1940)

The friend of a lifetime whose genius united the insight of the Metaphysician, the interpretative power of the Critic and the erudition of the Scholar

DIED AT PORT BOU (SPAIN)

ON HIS WAY INTO FREEDOM

II. Civilization & barbarism

A victory arch commemorates a victory procession that ended there, or at least ended where the arch was later to be constructed. The Arc de Triomphe was drawn up for that purpose. After winning at Austerlitz in 1805, Napoleon promised his soldiers that they would "return home through arches of triumph." The next year, he commissioned the Arc de Triomphe to provide those arches, though the monument wasn't completed until 1836.

The Arc de Triomphe was modeled after the Arch of Titus, constructed to celebrate the Roman general and then-future emperor Titus's victories, particularly his victory in 71 C.E. over Judea's rebellious Jews.14 The Arch of Titus's high relief depicts the victory procession from the destroyed Jerusalem to Rome. It shows bound prisoners, presumably leaders of the rebellion. During the celebration at the end of the procession, two of the leaders were ceremoniously killed.

Benjamin writes about "such pieces of architecture, their origin in ancient Rome, [and] their political and ideological functions," Michael Löwy points out.15 Benjamin, Löwy says, was interested also “in parallels between Roman and modern imperialism." Benjamin probably would have been particularly interested in the Arch of Titus's high relief "showing the Jewish menorah as a spoil in the victorious parade of the Roman armies."16

Even if they don't always depict them in relief, victory arches invite these past victory parades into the present. In a different way, Benjamin thinks that past victory parades are always manifest in present civilizations. He writes in Thesis 7 of how rulers step into the shoes of preceding conquering rulers:

. . . all rulers are the heirs of those who conquered before them. . . . Whoever has emerged victorious participates to this day in the triumphal procession in which the present rulers step over those who are lying prostrate.17

The violent origin of rulership extends to what we call culture, revealing it as the poisonous fruit of violence:

According to traditional practice, the spoils are carried along in the procession. They are called cultural treasures . . . There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.18

Titus's father, the emperor Vespasian, built a temple near the Arch of Titus, which served as a kind of museum where visitors could see the menorah and the table of shewbread looted from the Jerusalem temple. A Khan Academy video about the Arch of Titus describes this ancient museum as "not a museum like our museums, [but] a museum of war booty and of trophies collected by a man who was about to become a god himself."19

Benjamin, however, would find no such distinction between Vespasian's museum and our own museums. Every document of civilization, he says, is also a document of barbarism. Today's slow return of artworks to the peoples from whom they were stolen amounts to grudging proof of Benjamin's equation.

But Benjamin's assessment of civilization suggests a more fundamental problem than the violent origins of its culture. Like his characterization of the "current amazement" over fascism, Benjamin's account of civilization calls into question our model of history as the story of uneven but inevitable progress from barbarism to civilization.

What is barbarism from civilization’s standpoint? We can find an answer from ancient panels like the high relief in the Arch of Titus. Sylvia C. Keesmaat describes and comments on a surviving panel from the Sebastion of Aphrodisias in Asia Minor, which depicts conquered peoples as a woman:

The final image . . . is of Claudius being crowned by the Senate with a captive woman at his feet. As [Harry O.] Maier points out, “The classical serenity of Claudius crowned by a properly coiffed and dressed matron who represents Rome contrasts with the terror of the subjugated female depicted in Hellenistic style, who kneels, with bare breast and falling hair.” Her hands are bound behind her back. The message is clear: the conquest of foreign peoples is the basis for the emperor’s authority. The fact that in many of these images the emperor is naked evokes not only divinity but also the threat of sexual violence toward the women. These were captive peoples depicted with immodest clothing and wild hair because they were themselves immodest and wild, unable to control their passions and in need of Roman culture and civilization. Portraying them as women emphasized not only their weakness but also their emotional, irrational nature. They are meant to be subjugated. The emperor, on the other hand, is calm and rational, and his naked body reveals his authoritative male character. It is because he is male and rational that the emperor is entitled to be dominant and expected to conquer.20

Barbarians were wild, irrational people "in need of Roman culture and civilization."

Our way of telling history is essentially as these Roman panels tell it, Benjamin would say. We are the heirs of the Romans who conquered before us. Civilization labels its victims as barbarians, but civilization itself is barbaric.

If civilization and barbarism are the same, what public space is left for our common life? Is there any escape from rule and oppression that Benjamin associates with civilization itself? Benjamin draws hope from Kabbalism, in what he calls every generation's "weak Messianic power."21

III. Messianic mysticism & political action

Scholem suggested that Benjamin's essentially religious approach in "Theses" was precipitated a year before his death by the Hitler-Stalin Pact.22 There's something to Scholem’s claim: Benjamin suggested that the pact disaffected him from the Soviet Union’s policies if not from what his thinking had adopted from Marxism.23

Besides, Benjamin was, according to Löwy,

opposed to the evolutionist and positivistic brand of ‘scientific socialism' dominant in the Social Democratic and Communist labor movement. For him, the task of the historical materialist is to break, explode, destroy the conformist thread of historical and cultural continuity.24

Benjamin’s articulation of history involves an interruption of the present by the now-embodied past, so Communism’s determinism was as foreign to his philosophy of history as the prevalent Western belief in inevitable progress.

But as an inspiration to Benjamin’s “Theses,” Scholem didn’t give himself enough credit.25 Both Benjamin's and Arendt's biographers assert that Benjamin's "Theses" arose out of discussions Benjamin had with Arendt and Blücher about Scholem's own manuscript on Jewish mysticism.26 Benjamin, Arendt, and Blücher were particularly interested in Scholem's account of the seventeenth-century's Sabbatian movement and its "combination of a messianic mystical tradition with an active political agenda."27

Scholem's treatment of the Sabbatian movement inspired Arendt to write, too. In her essay "Jewish History, Revised" published in 1948, she connected the Sabbatians' understanding of Messianic hope as the impetus for unprecedented Jewish political action:

. . . never before had a huge popular movement and immediate political action been inspired, prepared, and directed by nothing more than the mobilization of mystical speculations. The hidden experiments of Jewish mystics through the centuries, their efforts to attain a higher reality which, in their opinions, was hidden rather than revealed in the tangible world of everyday life or in the traditional revelation of Mount Sinai, were repeated on a tremendous and absolutely unique scale, by and through the whole Jewish people. For the first time, mysticism showed not only its deep-seated hold on the soul of Man, but its enormous force of action through him.28

In his own more vertiginous writing, Benjamin seems to agree with Arendt in principle about the potential in Messianic tradition for action. His "Theses" uses the same connection between Messianic mysticism and political action to suggest how public spaces and their "essential, intensive, all-inclusive temporality," as Irving Wohlfarth describes Benjamin's conception,29 can interrupt civilization and its "homogenous, empty time."30

IV. A proper articulation of the past: our calling to interrupt

The hope of Benjamin's "weak Messianic power" starts with a repurposing of civilization's concepts. It then moves to interrupt civilization's ordinary time and thereby to create public space. In other words, Messianic power starts in present weakness to awaken a power oriented in the past. It moves from a subversion of civilization's present understandings to an alternative form of politics.

Benjamin's Thesis 8, for instance, indirectly subverts the Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt's 1922 concept of the sovereign as he who decides on the exception to the rule of law—that is, as he who decides on the state of emergency. The Nazis, of course, had suspended Germany's constitution in 1933, asserting the "emergency" of the Reichstag Fire. Benjamin subverts Schmitt's philosophy by putting Schmitt's "state of emergency" to his own use:

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the "state of emergency" in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight. Then we shall clearly realize that it is our task to bring about a real state of emergency, and this will improve our position in the struggle against Fascism.31

Benjamin's "real state of emergency" is the interruption of what he calls "a homogenous, empty time."32 The interruption begins as an allegory or a reference—in essence, a memory:

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it "the way it really was" (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.33

Here, in Thesis 6, we find the plainest statement of Benjamin's theory of history.

Benjamin's statement suggests that the true articulation of the past enlivens the present otherwise emptied by civilization. It amounts to, in Wohlfarth's words, "the compression of ordinary time and the concomitant emergence of another, more originary temporality." This ontological temporality is connected with our status as "a beginning and a beginner," to use Arendt's expression to describe essentially the same interruption.34

When Benjamin introduces his concept of a "weak Messianic power" in Thesis 2, he puts our relation to the past and our relation to a transformed present in inspiring terms:

There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth. Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim. That claim cannot be settled cheaply.35

We were born to interrupt. Moses interrupted. Jesus interrupted. They interrupted empires with what Benjamin describes as a "weak Messianic power." Even their respective nativity stories, highlighting their weakness, show that their "coming was expected on earth." As Kaitlin B. Curtice points out, "all children are liberators."36

Above: the only known photo of Walter Benjamin smiling (third from left). Information about the photo can be found on WalterBenjaminDigital.

But tyranny also claims the past—not all past, as Messianic time does, but a purported golden age with which tyranny attempts to wallpaper the future. In Thesis 14, Benjamin compares such historicism to a fashion show:

The French Revolution viewed itself as Rome reincarnate. It evoked ancient Rome the way fashion evokes costumes of the past. Fashion has a flair for the topical, no matter where it stirs in the thickets of long ago; it is a tiger's leap into the past. This jump, however, takes place in an arena where the ruling class gives the commands.37

Compare tyranny's attempt to dress up the future with Benjamin's use in Thesis 18 of the Torah's prohibition against soothsayers:

We know that the Jews were prohibited from investigating the future. The Torah and the prayers instruct them in remembrance, however. This stripped the future of its magic, to which all those succumb who turn to the soothsayers for enlightenment. This does not imply, however, that for the Jews the future turned into homogenous, empty time. For every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.38

Benjamin in this final thesis would agree with historian Timothy Snyder, who uses the term “the politics of inevitability” to describe what Benjamin calls “progress,” and who uses the term “the politics of eternity” to describe what Benjamin labels as historicism. (For Benjamin and Snyder, fascism is a purveyor of this latter philosophy of history.) One can also read in Snyder what Steiner calls Benjamin’s “primacy of the political” over history:39

History is and must be political thought, in the sense that it opens an aperture between inevitability and eternity, preventing us from drifting from the one to the other, helping us see the moment when we might make a difference.40

Snyder, like Benjamin, is identifying a philosophy of history as an alternative to civilization’s binary philosophies of history. Snyder’s “moment when we might make a difference” is, I think, precisely Benjamin’s “every second of time,” the “strait gate” that makes way for our agency in public space.

Benjamin in this final thesis also agrees with Arendt's take on the politically enervating result of looking into the future: ". . . Progress and Doom are two sides of the same medal; that both are articles of superstition, not of faith."41 Like Benjamin and Snyder, Arendt identifies the same two philosophies of history (Arendt’s “Doom” corresponding to Benjamin’s “historicism”) that keep us from acting in faith to create public space.

How can we then live faithfully with the hopeful but uncertain future that Benjamin articulates? We reference the past. The past's true claim—the liberating claim that's made with Benjamin's "essential, intensive, all-inclusive temporality"—teaches us to treat this world's cultural treasures stolen from the defeated with what Benjamin calls "cautious detachment."42 Paul (Saul of Tarsus, the Benjamite) makes the same point, calling for “cautious detachment” in more familiar language:

The present situation won't last long; for the moment, let those who . . . use the world [use it] as though they were not making use of it. The pattern of this world, you see, is passing away.43

Paul's "state of emergency," his “present distress” as the King James Version puts it,44 is like Benjamin's: it's taught by the "tradition of the oppressed."45 Benjamin's appropriation of Schmitt's "state of emergency" is, one might say, a literary application of Paul's advice to use the world "as though they were not making use of it." Benjamin uses Schmitt. As Steinberg observes of Benjamin’s Thesis 8, "With Schmittian language, he works out an anti-Schmittian politics."46

This fully participatory, Messianic politics can't come cheaply, as Benjamin suggests. Uprooting our lives from what Paul describes as a persistent but fading world, fabricated by civilization after civilization, is one great cost of our Messianic calling. As we pay this cost, we can begin to practice Benjamin's subversion: we can repurpose the world's oppressive concepts, when necessary, to articulate liberation after liberation.

V. Paul (and us) in Messiah’s victory procession

Like Benjamin, Paul was a Jewish intellectual who championed the defeated and who died at the hands of an expanding empire. His writings, like Benjamin's, are dense with "political, historical, and theological motifs." And his political motifs, like Benjamin's, are mostly stolen from his age's civilization.

Paul and Benjamin, in fact, share a political motif: victory processions. The Roman Empire was expanding, and Paul's assemblies, made up of defeated peoples, were familiar with these processions from sculpture, coinage, furniture, palace ceilings, oil lamps, and their own cities' streets.47 The victory processions and other assertions of Roman victories were part of the Roman Empire's use of imagery in what had become, as Averil Cameron puts it regarding second-century Rome, "in political terms a spectator culture."48 Harry O. Maier thinks Cameron’s phrase applies to first-century Rome, too.49 Rome developed its spectator culture to assert its exclusive right to public space at the expense of nations whose political lives would not extend beyond that of mere spectators.

In Paul's reworked victory procession, though, the situs of government is not Rome but a heaven arriving on earth. The bound prisoners are Paul himself and his fellow barbarian saints:

But thanks be to God, who continually leads us as captives in Christ’s triumphal procession, and uses us to spread abroad the fragrance of the knowledge of himself!50

Paul here subverts Rome's visual rhetoric to identify himself with "the barbaric 'other,'" as Keesmaat points out:

By identifying both Jesus and himself with those who are considered the barbaric “other,” Paul is undermining the visual rhetoric that sought to depict other peoples as worthy of enmity or conquest.51

Paul depicts himself as weak, but he suggests that Messiah has conquered him not with violence but with love. Paul is accused by some in the Corinthian church as being, in some ways, weak. In response, Paul asserts his power, but he never denies his weakness. In fact, Paul paradoxically links Messiah's own weakness with power:

True, he died on the cross in weakness, but he lives by the power of God; so you will find that we who share his weakness shall live with him by the power of God.52

Paul's identification of himself as a captive with the defeated Corinthians in a victory procession celebrates this paradoxical weakness. His identification of the crucified Messiah as the victor in this procession connects weakness with Messianic power.

This Messianic glory expressed "in Christ's triumphal procession" is within the assembly of the defeated, Paul says: "And this is the key: the king, living within you as the hope of glory!"53 To borrow Benjamin's term, this "weak Messianic power" can disrupt empires, putting public space in the hands of the defeated.54

Luke relates an example of this powerful "king, living within you," ironically turning his pro-Roman speaker into the spectator (and so, in a sense, turning the world upside down):

The men who have made trouble the whole world over have now come here, and Jason has harboured them. All of them flout the emperor’s laws, and assert there is a rival king, Jesus.55

Paul, of course, is among Luke's once-defeated troublemakers.

Above: Walter Benjamin

Paul is even willing to misquote scripture to side with the defeated in a victory procession. In Ephesians, he claims to quote Psalm 68:

Therefore it says, “WHEN HE ASCENDED ON HIGH, HE LED CAPTIVE THE CAPTIVES, AND HE GAVE GIFTS TO PEOPLE.”56

But Paul in that passage reverses the giving. In the psalm, the conquered people give tribute to the conquering king:

You went up to the heights, having taken captives, having received tribute of men, even of those who rebel against the Lord God's abiding there.57

(Paul and Benjamin, therefore, have another similarity: Paul shares what Wohlfarth calls "Benjamin's penchant for quoting out of context."58)

As Maier points out, Paul's reversal of the gift's direction in the royal psalm also reverses notions of power:

Even as Ephesians revises Ps. 68.18 to make God the giver of gifts, it also changes the imperial notion of triumph.

The Romans used the spoils of war to pay their armies and to build their temples and monuments, such as the Arch of Titus.59 But Paul makes himself and all of us spoils of Messiah's victory, much as he makes us captives in Messiah's victory procession. As the passage in Ephesians continues, we learn that, as the spoils of Messiah’s loving conquest, we are given by Messiah to his assemblies to equip their members for "their work of service, and so to build up the king's body."60 As spoils, we are not hoarded by a victorious Messiah but are given away.

Suddenly an imperial spectacle meant to rob the vanquished of public purpose becomes a purposeful, even inspiring public spectacle in which we participate. Paul’s account of our status as captives and as booty echoes Benjamin's assertion that "Our coming was expected on earth" and Benjamin’s association of our advent with our "weak Messianic power."61

Paul's entire strategy of appropriating imperial images of horror—whether of crucifixion or of victory processions—asserts an alternative political community to those established on the civilization-versus-barbarian framework, according to Maier:

. . . Paul continually prompts his audiences to place before their eyes pictures of self-sacrifice and humiliation not to glory in a kind of Nietzschean 'slave morality', but to articulate a way of being in an alternative commonwealth on earth, under the rulership of its crucified Lord and Saviour.62

Whether the Messiah has come, as Paul asserts, or whether the Messiah has yet to come or will never come as a single individual, as Benjamin may have believed, Paul's and Benjamin's understandings of our "weak Messianic power" seem functionally close, particularly as they assert an alternative means of public space in response to the oppressive political structures of their respective eras.

VI. Public space on a Lisbon dock

As they waited in Lisbon for a ship to America, Arendt and Blücher read the manuscript of "Theses" to a group of their fellow refugees. It was spring; Benjamin had died the previous fall. Arendt's biographer says that the group "discussed and debated the meaning of his moment-to-moment messianic hope."63

I wish I could have been there. I imagine Arendt bringing up some of the same points from her earlier discussion with Benjamin and Blücher about Scholem's book on Jewish mysticism.

I imagine Arendt sitting on a Lisbon dock, surrounded by her husband and her disoriented friends and new acquaintances and together, in a kind of impromptu book club, creating public space. I hear her, consistent with her later essay about Scholem's book, relating Messianic hope to political action.

Two years later, Arendt wrote what her biographer calls "a poem for her dead friend, a farewell and a greeting." It contains three stanzas, and she entitled it simply "W.B." The middle stanza, to me, suggests what we might glean from one claim by the past on our weak Messianic power that wasn't settled cheaply.

Out of the darkness sound softly / small archaic melodies. Listening, / let us wean ourselves away, / let us at last break ranks.64

Above: napkin this month at Fort Worth’s Wicked Butcher.

The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the earlier manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography. The longer footnotes refer to works not referenced in the manuscript.

Pfanner, Helmut F. “Trapped in France: A Case Study of Five German Jewish Intellectuals.” Museum of Tolerance, Los Angles, 2024. https://www.museumoftolerance.com//education/archives-and-reference-library/online-resources/simon-wiesenthal-center-annual-volume-3/annual-3-chapter-4.html.

Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World, 2. ed (New Haven, Conn., London: Yale University Press, 2004), 161.

Howard Eiland and Michael William Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014), 659.

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1986), 257. Italics in the original.

Proverbs 1:7.

Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn, 1st Picador USA ed (New York: Picador USA/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002), 129.

Michael P. Steinberg, “Introduction: Benjamin and the Critique of Allegorical Reason,” in Walter Benjamin and the Demands of History, ed. Michael P. Steinberg (Ithaca (N.Y.): Cornell university press, 1996), 10.

Eiland and Jennings, 648.

Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship (New York: New York Review Books, 2012), 40.

Steinberg gives a summary of some of these battles. Steinberg, 4-5. See also Uwe Steiner, Walter Benjamin: An Introduction to His Work and Thought (Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 18.

Lee Siegel, “Introduction,” in Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship, by Gershom Scholem (New York: New York Review Books, 2012), vii.

Steinberg, 4.

Eiland and Jennings, 659.

Paris Digest. “Arc de Triomphe Facts,” December 26, 2019. https://www.parisdigest.com/monument/arc-de-triomphe-facts.htm.

Michael Löwy, “‘Against the Grain’: The Dialectical Conception of Culture in Walter Benjamin’s Theses of 1940,” in Walter Benjamin and the Demands of History, ed. Michael P. Steinberg (Ithaca (N.Y.): Cornell university press, 1996, 206–13.), 209.

Löwy, 208.

Benjamin, 256.

Benjamin, 256.

Steven Fine and Beth Harris, “Relief from the Arch of Titus, Showing The Spoils of Jerusalem Being Brought into Rome,” Smarthistory, accessed October 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-arch-of-titus-2/.

Keesmaat, “Citizenship and Empire,” 245-46.

Benjamin, 254.

Scholem, 276.

Eiland and Jennings, 658.

Löwy, 208. Italics in the original.

Steiner describes Scholem's account of the inspiration for the "Theses" as "too narrow" from an historical standpoint. Steiner, 166-67.

Eiland and Jennings, 659; Young-Bruehl, 161-62.

Eiland and Jennings, 659.

Hannah Arendt, “Jewish History, Revised,” in The Jewish Writings, by Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 2007, 303-311), 310.

Irving Wohlfarth, “Smashing the Kaleidoscope: Walter Benjamin’s Critique of Cultural History,” in Walter Benjamin and the Demands of History, ed. Michael P. Steinberg (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1996, 190-205), 193.

Benjamin, 261.

Benjamin, 257.

Benjamin, 261.

Benjamin, 255.

Arendt, Between Past and Future, 166-69.

Benjamin, 254. Italics in the original.

Kaitlin B. Curtice, Native: Identity, Belonging, and Rediscovering God (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2020).

Benjamin, 261.

Benjamin, 264. Writing about this distinction in Benjamin's thinking, Steinberg speaks of Benjamin's engagement of history through reference and Benjamin's understanding of the fascists' engagement of history through representation. Steinberg, 8. The historian Timothy Snyder calls this engagement of history through representation the politics of eternity. For Snyder, attempting to make the future like the past eliminates the present moment in public life. Snyder, Road to Unfreedom, 8.

Steiner, 170-71.

Snyder, 12-13.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, A Harvest Book (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1994), vii.

Benjamin, 256.

1 Corinthians 7:29, 31 translated in Wright, Kingdom New Testament, 348. The world “passing away” has nothing to do with the end of “the world of space, time, and matter,” as N.T. Wright never tires of reminding us, but with (in all likelihood) the end of what Paul calls elsewhere the “present evil age.” Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Parts 1 & 2), 525, 562; Galatians 1:4 (NNAS). Understanding the Bible to warn of the end of the physical world is another means of de-politicizing Jesus’s political, religious, social, and spiritual gospel and to consign the kingdom of God and its public realm to futility.

1 Corinthians 7:26 (KJV & NNAS).

Benjamin, 257.

Steinberg, 15.

Harry O. Maier, Picturing Paul in Empire: Imperial Image, Text and Persuasion in Colossians, Ephesians and the Pastoral Epistles (London ; New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 41.

Averil Cameron, quoted in Maier, 5.

Maier, 5.

2 Corinthians 2:14 REB.

Keesmaat, 247.

2 Corinthians 13:3 REB.

Colossians 1:27, translated in Wright, 410.

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben explores the connection between Paul and Walter Benjamin on the level of messianic thought. Giorgio Agamben, The Time That Remains: A Commentary on the Letter to the Romans, trans. Patricia Dailey, Nachdr., Meridian, Crossing Aesthetics (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2006), 138-45. Agamben asserts that Benjamin derived his notion of a “weak Messianic power” from reworking Paul’s notion of a weak messianic power in 2 Corinthians 12:9-10, especially Messiah’s assertion to Paul that “power fulfills itself in weakness” (139-40). Agamben goes so far as to call Paul’s passage in 2 Corinthians and Benjamin’s Theses "two fundamental messianic texts of our tradition.” Using Benjamin’s terminology, Agamben says that the two texts “form a constellation whose time of legibility has finally come today, for reasons that invite further reflection” (145). I wasn’t aware of Agamben’s connection of Paul’s and Benjamin’s messianic thought until after I wrote this post, but I hope that the post constitutes some of this well-deserved reflection.

Acts 17:6-7 REB.

Ephesians 4:8 NASS.

Psalm 68:19, translated in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., The Jewish Study Bible: Jewish Publication Society Tanakh Translation, 2. ed (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2014), 1341.

Wohlfarth, 197.

Maier, 135.

Ephesians 4:11-12, translated in Wright, 395.

Benjamin, 254.

Maier, 51.

Young-Bruehl, 162.

Young-Bruehl, 163.