The public life of caves

I have something too public to share. But I'll share ten cave tips instead.

Well into writing you about what's really going on, I grow uneasy. I end up not sharing it. What's going on isn’t a big deal, and I don't mean to be mysterious or dramatic by bringing it up. Writing about it helps me process things, but sharing it just wouldn't be smart.

I bring it up only because what's going on is public. It's not too personal to share. It's too public to share.

A hidden public life sounds like an oxymoron, and I guess it is. But oxymorons speak in contradictions to get at something greater, right?

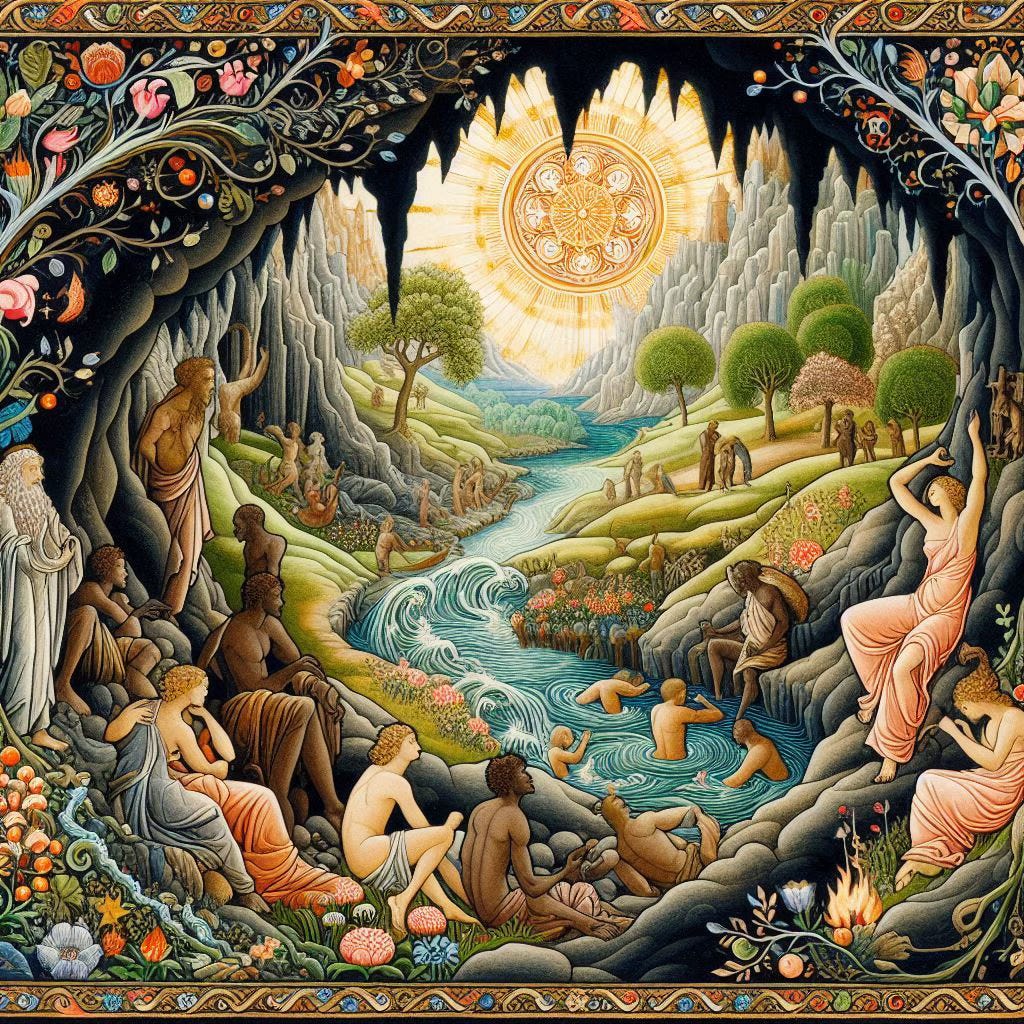

I've been thinking recently about a few of the Bible's more crowded caves. One is "the cave Adullam," where David fled from King Saul.1 Two others are Obadiah's caves, where he lodged a hundred prophets of YHWH during their persecutions by King Ahab and his wife Jezebel.2

These hiding places were public spaces. The more I read about these caves, the more they suggest a model—or, really, some possible components for your own new models—of public life in this age.

I'd like to do a little scriptural spelunking to get across these components in the form of ten tips for public life today.3 To see in these caverns, we'll need to generate light with what William T. Cavanaugh calls our "theopolitical imagination." In doing so here, I use mostly references perhaps familiar to my fellow Christians, though employed in ways not familiar to most Christians I know.

But I hope my esoteric references exclude no one. My model—only, I'm afraid, in this limited respect—is Martin Luther King, Jr., who despite his biblical allusions managed to speak to everyone, not just Christians.

Let’s start with what I won’t share.

Tip 1: Be open to hidden public spaces.

This oxymoron of hidden public space is pretty much a Hannah Arendt thing. She claims that after the Nazi conquest of France, members of the new résistance "came to constitute willy-nilly a public realm" that was "without the paraphernalia of officialdom and hidden from the eyes of friend and foe."4 The résistance, she says, amounted to a "public realm" that was "hidden."

One American version of hidden public space was the Underground Railroad, the work of Harriet Tubman and many others attempting to help slaves escape to freedom.

Much public space, of course, still must appear to everyone near it. One fascinating resource for creating open public space is Gene Sharp's 1973 book The Methods of Nonviolent Action. His 198 methods include public speeches, petitions, picketing, public prayer and worship, vigils, singing, pilgrimages, teach-ins, walk-outs, silence, social disobedience, disguised disobedience, nonviolent occupation, guerrilla theater, and alternative markets.

Tip 2: Create or join alternative political communities.

But I think the best public space, open or hidden, happens in alternative political communities. While David was in the cave, his family and about four hundred other people joined him. They formed a community that became the heart of David's political movement.

The church began this way, too. The Roman Empire, as N.T. Wright points out, was as religious as it was political, and the assemblies of Jesus-followers were as political as they were religious.5 Jesus and Paul both wanted to build alternatives to the world's empires, and they started communities to serve as prototypes of God's future rule on earth.

We consider Paul's writings to be influential, but he didn't intend them for distribution beyond his assemblies. He never wrote to the world. Instead, the assemblies, Paul said, were the Messiah's living letters to the world.6 Life and action together speak louder than (as with this Substack) words by individuals.

Tip 3: Don't wait to get desperate.

The Jesus assemblies attracted political outsiders, including women and slaves who were given political power unavailable to them in imperial Rome. Paul noted that not many of the Jesus assembly members had come from cultivated, powerful, or noble backgrounds.7

Paul's assembly members resembled the people who joined David in the cave Adullam: "everyone who was in straits and everyone who was in debt and everyone who was desperate joined him . . ."8 Robert Alter describes them as "men with nothing to lose who have been oppressed by the established order."9

If necessity is the mother of invention, then desperation may be the mother of faith. My favorite Bible story in this regard involves how Samaria was saved from an Aramaean siege. A disreputable, alternative community of exactly four lepers, acting merely out of desperation for food, saved the city.10 Oppressed subcultures are often at the forefront of creating public space by faith.

If you're cultivated, powerful, or noble, find and serve those "in straits." Don't be a revolutionary. That is, don't try to commandeer these people or mold them into your ideology. Learn from these people. In fact,

Tip 4: When standard political concepts aren't working for you, cross a boundary.

Sometimes what keeps us from the kingdom of God is our limited life experience. Jesus challenged the rich young ruler seeking a role in God's new age not to adopt some creed or pray some prayer but to walk on the wild side.11 Join those in straits, in debt, or in a desperate place, or at least those who can't afford all of our dominant culture's means of maintaining privacy and security. Explore real public spaces.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer preached the German version of Christian nationalism until he started hanging out at a Black church in Harlem. For a year while studying at a New York seminary, he frequented and served Adam Clayton Powell, Sr.'s Abyssinian Baptist Church. Far more than his studies at the seminary, Bonhoeffer's encounters at this alternative political community changed his theology and the trajectory of his life.

Find someone or some people, like Jesus, who walk through locked doors.12 When you find them, move around with them and watch them in different contexts. Learn how to network like them. If you travel, break off from the official tour and meet people. If you don't have time or money to travel, then cross your own town's tracks. You'll probably find great subcultures there, too. Political frameworks and concepts will occur to you while visiting other cultures and subcultures.

David could talk with anybody. On the lam from Saul, David crossed boundaries and cultivated relationships with Philistines and Moabites.13 Saul couldn't do that.

Tip 5: Stop doing politics in binaries.

Saul didn't cross cultural boundaries because he was stuck in the kind of binary thinking that precludes relational possibilities in public spaces. Saul's animosity towards David began with a musical binary: after military victories, Israel's women took to singing that "Saul has slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands.” Saul heard it like poll numbers: he was losing to a new challenger for his crown.14

In a multi-party system—and especially in a two-party system—elections narrow issues down to binaries. In these systems, our opinions, which are the lifeblood of democracy, matter little since no forum exists to hear them and to possibly revise and implement them. We are told to call or write our representatives, which I have often found to be a demeaning experience.

To win elections, parties refine a few opinions, as a factory may refine healthy food, and make them ingredients in prepackaged ideologies. Ideologies drive polities into a kind of madness—and, parties hope, to the polls each November.

The women's binary lyrics triggered a violent episode of Saul's madness. He had experienced previous episodes of "an evil spirit from God,"15 but this time he became violent. He started throwing spears at David inside his house.16

When we start doing politics in human-scale communities instead of allowing others to do it for us through our annual proxies, we'll move away from binary political thinking. We won’t be thinking of the Other as an abstract enemy, which elections encourage. We'll move closer to becoming what Martin Luther King popularized as "the Beloved Community."

The Beloved Community began as an act of American philosopher Josiah Royce's theopolitical imagination. He understood Paul's churches as assemblies where binary thinking would give way to triadic thought—that is, thought that honors the roles not only of the speaker and their opinions but also of the listener and their interpretations. In this Beloved Community, opinions would lead to interpretations, which themselves would be interpreted. The community would become a living political organism, and its members would discover their political callings.

Moving away from binaries can bring hope to this dark time. In previous national crises, some people recognized possibilities that went beyond the strongly held ideologies of either side. For Benjamin Rush, writing the year following the Revolutionary War and three years before the Constitutional Convention, the political cement seemed wet: "In America, everything is new and yielding," he enthused.

The Civil War’s horror wasn’t mitigated by emancipation, but it was attended by it—a result that, Lincoln implied, neither side foresaw at the war’s outset. His Second Inaugural, often considered the finest American speech ever written, recites some of the binaries that existed before and during the war before it gives way to some triadic and theological expression, beginning with “The Almighty has his own purposes.”

I’ve taken to frequenting sites that raise and discuss possibilities beyond ideologies—stuff for times of wet cement. Two of my favorite Substacks in this regard are Elle Griffin’s The Elysian and Peter Clayborne’s Anarchy Unfolds.

Tip 6: Rule out violence and its theory of rule.

David never threw spears back at Saul. While Saul and his army were chasing David, David twice had the opportunity to kill Saul. One time, he caught Saul relieving himself, and another time he discovered Saul and his men asleep. But David refused his followers' advice to kill Saul.17

Jesus taught and practiced political nonviolence. He would not become king with the sword. The New Testament teaches instead that Jesus became the world's king when he died on the cross.

We don't fight flesh and blood, Paul reminds us. But we do confront the dark powers behind flesh-and-blood rulers. In doing so, we wear "the breastplate of justice." We wield "the sword of the spirit, which is God's utterance.”18 God's now-word allows contingency to break into chronological history, a history otherwise written by this world's victors.

Tip 7: Contingency is destiny.

David didn't take matters into his own hands by killing Saul, but he also didn't succumb to political quietism. Samuel had anointed him king, which would have driven most people, I suppose, into either violence19 or quietism.

While based at the cave Adullam, David evidenced his contingent outlook with the care he took for his parents. He asked the king of Moab to keep them "until I know what God will do for me."20 Here David exemplifies both action and caution instead of their respective caricatures, violence and quietism.

David's "until I know" mirrors Mordecai's "who knows," as in his famous line to Queen Esther: "And who knows whether you have not attained royalty for such a time as this?" And Esther's response—"If I perish, I perish"21—isn't fatalism. It's an expression of the contingency of destiny.

As it happens, she didn't perish. But she could have.

David and Mordecai anticipate what early Christians called secular time, the break in chronological time brought on by Messiah's crucifixion that permits our public actions to matter. Without secular time, we’d have only the end time and standard, chronological time that marches inexorably towards the end time. We'd have to choose between making history (an essentially violent activity) and doing nothing (an essentially fatalistic position).

If we work to use this world's power to achieve Messiah's ends, then we'd attempt to “immanentize the eschaton,” in philosopher Eric Voegelin's words.22 In essence, we'd work in purely chronological time to end chronological time. Christian nationalists who seek to take over political structures for religious ends seek to immanentize the eschaton and ignore the power and weakness of moving in the Messiah's subversive kairos time—that is, in contingent secular time.

David's contingent strategies for exploring his destiny could be summarized as a combination of the democratic practices of waiting to learn what's next and acting to learn what's next. Throughout his flight from Saul, David prayerfully and advisedly sought direction for what to do next. He also acted and then learned what do to next from the results of his actions.

We exercise faith, Luke Bretherton says, by practicing a "faithfully secular politics."23 Paul offered similar advice to the church at Philippi: while ignoring Rome's offer of easy and sure salvation, assembly members must "work out your own salvation with fear and trembling."24 David and Esther lived this out in the context of earlier unjust regimes.

Tip 8: Use your privilege to subvert privileged power

Without succumbing to white savior complex or some variant thereof, use your privileged position to benefit those who suffer at the hands of the privileging power.

Obadiah was a high official in Ahab's administration, the steward of his palace. Presumably, he somehow used his high position to become the "steward" of two caves, where he housed a hundred of the Lord's prophets.25

Part of Mordecai's "who knows?" involved Esther's privileged position as queen. Esther took Mordecai's counsel, risking her life to approach the king and to set her plan for saving Israel in motion.

Mordecai's counsel to Esther came with a warning: "For if you keep silent at this time, liberation and rescue will arise for the Jews from another place, and you and your father’s house will perish."26 The lesson may be that, if we don't use our privilege to thwart the injustice of privileged power, then we may share in God's judgment against that privileged power.

Tip 9: Learn that anything is possible.

Privileged power often comes across as polite and cultivated, but when the dark forces behind it are threatened, it sets aside its refinement. It acts like a bloody tyrant.

Not long after David entered his cave, Saul incorrectly concluded that the Lord's priests had conspired with David, and Saul had them all slaughtered.27 Deuteronomy's constitution balances the powers of king, priests, prophets, and judges, but Saul destroyed this balance by destroying the priests. When the powers that be feel threatened, don’t rely solely on the Constitution's balance of powers or its other restraints on the exercise of power. Anything is possible.

It is not easy to accept that anything is possible. Writing five years before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, historian Marci Shore described the difference between the Eastern and Western mindset in terms of this understanding:

A quarter-century after the fall of communism, this was a divide that remained between East and West: Western Europeans—like Americans—tended to believe, even if only subliminally, that there were constraints on reality, that borders would hold, that certain boundaries would not be crossed. Eastern Europeans knew that anything was possible.28

Jesus said that, with God, "all things are possible."29 But it's hard to act politically on the hope that all things are possible without first learning that anything is possible.

One quote by African-American artist Carrie Mae Weems suggests to me how “anything is possible” and “all things are possible” can work together: "I knew, not from memory, but from hope, that there were other models by which to live." Tamar Avishai finds in these words "the exquisite hurt of rejection and a revolutionary rejection of the status quo."30

Tip 10: Don't depend on results. Instead, act as a witness.

The Bible's summary of these "other models by which to live" is New Jerusalem, which is last seen in the Bible on its way to earth.31 The heroes of faith found in Hebrews 11 all seek this city.32

One of my favorite cave verses hides among the Hebrews 11 heroes of faith. The cave dwellers are not among the heroes who accomplished a lot:

Through faith they overthrew kingdoms, established justice, saw God’s promises fulfilled. They shut the mouths of lions, quenched the fury of fire, escaped death by the sword.33

Instead, the cave dwellers are among the heroes who accomplished little except their own suffering, oppression and persecution:

They were stoned to death, they were sawn in two, they were put to the sword, they went about clothed in skins of sheep or goats, deprived, oppressed, ill-treated. The world was not worthy of them. They were refugees in deserts and on the mountains, hiding in caves and holes in the ground.34

The text makes no distinctions between the achievers and the cave dwellers:

All these died in faith, without receiving the promises, but having seen and welcomed them from a distance, and having confessed that they were strangers and exiles on the earth.35

None of the people cited in Hebrews 11 achieved what they ultimately wanted, but they confessed—testified by their actions—that a just political realm, from which they had come to earth as exiles, is also coming to earth.

James Baldwin calls something like this the "unwritten, dispersed, and violated inheritance" of Blacks that the Black church hands down from one generation to the next. "To live in connection with a life beyond this life," Baldwin says, is to become a custodian of this inheritance:

So you, the custodian, recognize, finally, that your life does not belong to you. This will not sound like freedom to Western ears, since the Western world pivots on the infantile, and, in action, criminal delusions of possession, and of property. But, just as love is the only money, as the song puts it, so this mighty responsibility is the only freedom. Your child does not belong to you, and you must prepare your child to pick up the burden of his life long before the moment when you must lay your burden down.36

Our living testimony of this public inheritance—of this just city—is the essence of freedom.

These dangerous times can move us to discover this freedom.

The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the earlier manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

1 Samuel 22.1-2.

1 Kings 18:1-4.

If you like this approach, you might enjoy a similar but nonsectarian list of public lessons for our day by a scholar and far more accomplished writer. In 2017, Timothy Snyder wrote On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century.

Arendt, Between Past and Future, 3.

Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness (Pts. 3 & 4), 1330, 1338.

2 Corinthians 3:1-3.

1 Corinthians 1:26.

1 Samuel 22:2 (JSB).

Alter, Hebrew Bible, vol. 2, 268n2.

2 Kings 7.

Matthew 19:16-22.

John 20:19, 26.

1 Samuel 21:11-22:4.

1 Samuel 18:6-9 NNAS.

1 Samuel 16:14-16 REB.

1 Samuel 18:10-11.

1 Samuel 24 and 26.

Ephesians 6:10-17; Hart, New Testament, 388.

Kind of like Macbeth after the witches’ prophecy.

1 Samuel 22:1-3.

Esther 4:12-16 REB.

McAllister, Revolt Against Modernity, 262.

Bretherton, Christ and the Common Life, 237.

Philippians 2:12 KJV.

1 Kings 18:3-4.

Esther 4:14 NNAS.

1 Samuel 22:6-21.

Shore, Ukrainian Night, 133.

Matthew 19:26 KJV.

Tamar Avishai, “Episode 50: Weems,” The Lonely Palette Podcast, accessed March 19, 2025, http://www.thelonelypalette.com/episode-50-weems.

Revelation 3:12; 21:2.

Hebrews 11:10, 16.

Hebrews 11:33-34 REB.

Hebrews 11:37-38 REB.

Hebrews 11:13 REB.

Baldwin, Devil Finds Work, 566-67. Italics in the original.