A few weeks ago, before three of us drove down to Alabama to encounter hundreds of hanging, rusting memorials to lynched African Americans, I had the wrong idea. I knew the hanging columns were rectangular, suggesting the unrecognizable and disfigured bodies of the lynched victims. But I thought each victim would get his or her own hanging column.

Instead, each county or city where one or more documented lynchings took place has its own hanging column. That still comes to 805 columns, arranged in a cloister that visitors walk through.

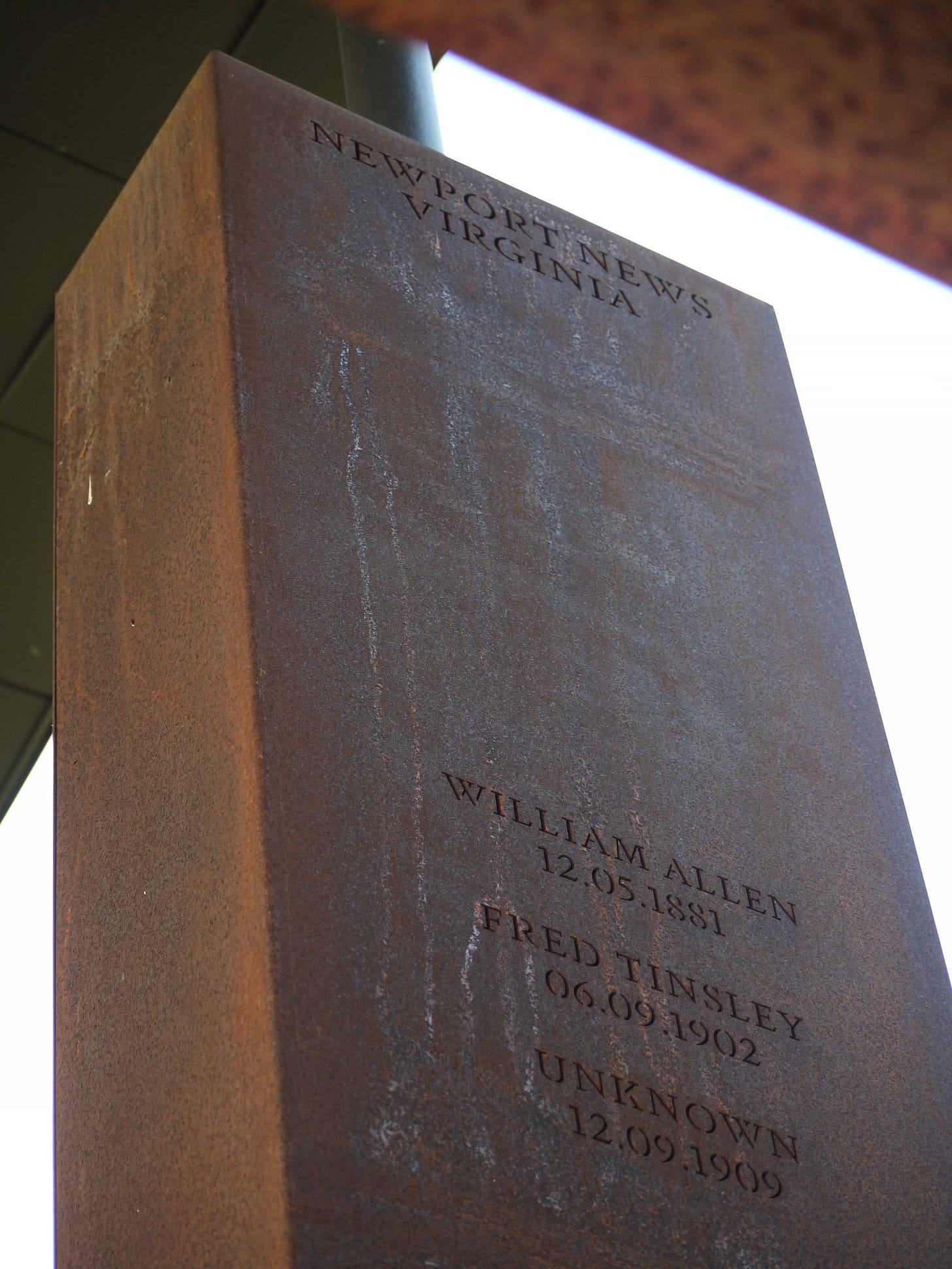

On each column, the name of the political jurisdiction, usually a county, but sometimes a city or an entire state, is engraved at the top. Below the county name, the names of the people lynched in the county are engraved.

Each column at Montgomery's National Memorial for Peace and Justice, then, is organized politically. Each column amounts to an implicit invitation to the named jurisdiction to reckon with its past. Outside the cloister, the invitation is explicit: duplicates of the columns lie in rows, like coffins of soldiers after a great battle, for jurisdictions to take home and put on public display.

The lynchings themselves were public, often drawing huge, celebratory crowds. By the turn of the twentieth century,

. . . gruesome public spectacle lynchings became much more common. At these often festive community gatherings, large crowds of whites watched and participated in the Black victims’ prolonged torture, mutilation, dismemberment, and burning at the stake.1

We looked for places we have lived. There's my hometown, Newport News, Virginia, where William Allen, Fred Tinnsley, and an unknown victim were lynched. There's Loudoun County, Virginia, where Victoria and I lived for over twenty years and raised our kids. In Loudoun, Page Wallace, Orion Anderson, and Charles Craven were lynched.

My connection to the fate of my fellow citizens in these communities took time to take in. But I walked on to what I found to be the most moving aspect of the memorial—the grassy, sloped quadrangle at the center of the cloister. A placard at the quadrangle's entrance says that it honors the victims of "hundreds of racial terror lynchings [that] took place in front of thousands of onlookers in public squares and on courthouse lawns."

As Paul might have said, these lynchings were not done in a corner.2 They were done often in what should have been the most public of spaces. The lynchings transformed these places of justice into mechanisms of racial tyranny.

I was ashamed.

That's good because shame is the goal—or at least it’s the means to some important goals. Brian Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative that created the memorial, finds that “without shame, you don’t actually correct. You don’t do things differently. You don’t acknowledge.”3

Shame is sometimes the first step to action, to justice, and even to political community.

That's the law and the prophets . . . or at least the Prophets and the Writings.

The lynching memorial is Hebrew-Bible prophetic

The lynching memorial, as Montgomery's six-year-old attraction is often called, is Hebrew-Bible prophetic. It shares in the prophets' vocation not to predict the future but to critique the past and urge the creation of a more just future. And like the Hebrew prophets, the memorial means to make us ashamed as a necessary first step toward creating a just community.

Much of the prophets’ shame is directed at rulers. The Hebrew Bible's prayers of repentance critique rulers, too, but we don't often read them that way. We often read the Bible's exilic prayers "as if the praying community is rejecting their circumstances and waiting for a return to power," theologian Daniel L. Smith-Christopher observes. Instead, he says, these prayers critique the oppression by Israel's past kings and other powerful people:

But it is the experiment with power that is carefully blamed and rejected in every prayer! The prayer does not allow the fantasy of power to go unchallenged.4

The Hebrew Bible's repentant prayers associate Israel's diaspora with the injustice of their past rulers. These prayers comport with the frequent messages of Israel’s prophets against both iniquity and injustice against the poor. This association between the present hearers and the past oppressors brings shame. The goal of the association and shame is to shield Israel from another "experiment with power" once they're free of foreign dominion.

Above: the quadrangle at the center of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice

The Bible holds us responsible for our ancestors' cruelty

Many Westerners, even many Christians, are uncomfortable with these biblical prayers that hold us responsible for the sins of our ancestors. In our own case, these sins would include the slavery of Africans and of Native Americans, the genocide of many Native American nations, and the expropriation of Native American lands. But the Bible couldn't be clearer about our need to confess our ancestors' sins:

If they confess their iniquity and the iniquity of their forefathers . . . [then] I will remember the land.5

We are to confess the iniquity of our "forefathers." In fact, the main focus of the Bible's repentant prayers is "the iniquity of their forefathers" in order to see them as shamed, Smith-Christopher concludes:

An important key is the notion of the shame of the ancestors. In short, it is not "our" shame that is the central issue (although this element is not absent). To recall shame on the ancestors is to recall history—to recall mistakes.6

Two examples from the Writings of repenting for our ancestors' iniquity will suffice here, though I recommend reading all of the scriptures cited in "Shame and Transformation," a chapter in Smith-Christopher’s book A Biblical Theology of Exile.7 From Daniel's prayer of repentance:

Open shame, O Lord, falls on us, our kings, our officials, and our ancestors, because we have sinned against you.8

From Ezra's prayer of repentance:

My God, I am ashamed and humiliated to lift up my face to You, my God, for our wrongful deeds have risen above our heads, and our guilt has grown even to the heavens. Since the days of our fathers to this day we have been in great guilt, and because of our wrongful deeds we, our kings, and our priests have been handed over to the kings of the lands, to the sword, to captivity, to plunder, and to open shame, as it is this day.9

Both Daniel's and Ezra's prayers explicitly express past shame and present-day shame for both their ancestors' and their own iniquity.

Guilt versus shame

Many people reject the Bible's counsel to accept shame because they confuse shame with guilt.

One way to appreciate the difference between guilt and shame is to compare their venues—guilt’s courtrooms and shame’s communities. Guilt is personal, a judicial determination that attaches to an individual because of something they did. Shame, though, is communal, something we communicate to one another when the community or one of its members has done something to threaten the community’s integrity.

This distinction between guilt and shame—the first relating to an “individual’s relation to God” and the second “a response to group opinion”—was fostered first by two church fathers, Tertullian and Augustine.10 More recently, theologian Mark G. Brett tracked this distinction between guilt and shame when discussing Australia’s crimes against its aboriginal population:

. . . guilt arises from personal involvement, as opposed to shame that can properly be felt for the crimes of earlier generations, and for inheriting the unjustly gained wealth of previous generations through colonialism. Such acknowledgment of shame, however, arises precisely from a sense of participation within a larger narrative of identity, whether for example the history of a church, or a national narrative.11

Daniel’s shame, which he shares with “our fathers”—his nation’s ancestors—is precisely Brett’s shame, stemming from “a sense of participation” in the history of a church or nation.

As we grow, we see not only our parents’ faults but also our communities’ sins. Shame allows us to stay in community, and it helps make our membership in those communities heathy and healing.

We're not guilty of our ancestors' crimes, but we must accept shame for them

Many argue—correctly—that they can’t be made guilty for their ancestors’ crimes. Since guilt, in the public sense, is a judicial determination that attaches to a person because of something they themselves did, collective guilt—an oxymoron—would undermine courts. To say, as many in post-World-War-II Germany did, that “we are all guilty” overlooks the personal nature of guilt and suggests that no one is guilty, Hannah Arendt points out. Arendt, a German Jew once jailed by the Nazis, believes that such postwar sentiments “only served to exculpate those who actually were guilty.”12

But Arendt insists on our collective responsibility for our nation’s crimes: “. . . we are always responsible for the sins of our fathers as we reap the rewards of their benefits,” she says.13 T.S. Eliot makes the same point, suggesting that along with what has become generational wealth, the great benefit from our rapacious forebears’ theft is the cross:

Whatever we inherit from the fortunate / We have taken from the defeated / What they had to leave us—a symbol: / A symbol perfected in death.14

Like the cross, our shame—our response to our collective responsibility—for our nation’s crimes is necessary and redemptive. However, since sin is “a disgrace to any people,”15 from the standpoint of God’s justice, denying that disgrace is a threat to any people. Unlike shame, shamelessness is not redemptive.

Psychological shame versus political shame

I think many people refuse to acknowledge their shame or the shame of their ancestors because they've experienced private shame from some act or omission—sometimes a horrendous act or omission by others. Self-help resources—many of them excellent—define shame as chiefly an individual experience that damages our self-worth. Brené Brown, for instance, offers this definition of shame:

I am bad. The focus is on self, not behaviour. The result is feeling flawed and unworthy of love, belonging, and connection.16

Brown rightly points out that shame, as she defines it, can be unjustly caused by others,17 just as shame is often unjustly caused by others in the Bible’s narratives.18

However, the Bible's repentant prayers justly generate shame, or justly aim to do so, and not guilt or humiliation, as Smith-Christopher points out:

These prophetic calls to shame in the context of history are not calls to a paralyzing personal guilt or humiliation. It is a call to recognize the constant failures of living according to alternative ideals and values—universally identified in the penitential prayers as the Mosaic laws. Shame, therefore, is not a psychology, it is a politics.19

The purpose of shame: every citizen's return to political responsibility

The purpose of shame as "politics" is to create political community around covenant. The Hebrew Bible’s Writings, in calling Israel to shame, were also calling Israel into the public realm. The Writings' repentant prayers targeted the ancestors in "precisely the period of the monarchy and the central period of prophecy," Smith-Christopher points out. What did their repentance during the period of kings and exile seek to return people to? According to Smith-Christopher, to the "ethics of Moses."20

The Prophets and the Writings understood Moses's constitution as grounded in justice and in overlapping areas of direct participation in public life. Republicanism was a major "political principle of biblical Israel," according to political science professor Daniel J. Elazar. For biblical Israel,

. . .republicanism reflects the view that the political order is a public thing (res publica), that is to say, not the private preserve of any single ruler, family, or ruling elite but the property of all its citizens, and that political power should be organized so as to reflect that fact.21

Though Elazar focuses on ancient Israel, he finds that "the American Declaration is an excellent example" of a covenant denoting "the voluntary establishment of a people and body politic."22 Fully realized as a covenant, the Declaration's Equality Clause would lead to justice for all and political participation by all.

Shame's role in the New Testament's alternative communities

This prophetic vision of justice and political participation, a vision fueled by the shame that Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, and others express, is also messianic. Elezar notes that "the biblical vision of the restored commonwealth in the Messianic era envisages the reconstitution of the tribal federation (Ezek. 47:13 - 48:35)."23

Elezar's understanding of Israel's messianic vision is similar to what Smith-Christopher calls a "politics of penitence" and its goal, "an alternative way of living":

To remind oneself constantly of the failure of power (in the ancestors and kings) is to advocate an alternative mode of living, not simply to pine for a change of status.

Israel’s shame for its past oppression, he says, would create "a break with the past . . . an alternative people of God."24

The New Testament, of course, asserts that the messianic era has begun. Jesus’s announcement of God's kingdom's arrival means also that the time for "an alternative mode of living" has begun. This alternative mode involves a turn from private and often selfish concerns to public life. Like Moses and the repentant prayers of the Writings, Jesus called Israel to public life. Many from Israel's villages who heard Jesus, and later many Gentiles in Paul's assemblies, formed themselves in alternative communities separate from Rome's influence and loyal to Jesus as the Messiah, whose death they believed had started the Messianic era.25

Covenant communities, particularly alternative communities struggling to exist under the shadow—and sometimes the persecution—of dominant cultures, function in part by loyalty and shame. Christianity, American philosopher Josiah Royce points out, is "a religion of loyalty."26 Theologian N.T. Wright suggests that pistis, the Greek word usually translated in English New Testaments as "faith" or "faithfulness," also means "loyalty," and in the New Testament's context loyalty to Jesus.27

Disloyalty brings shame. Warnings about shame appear frequently in the New Testament. John says, for instance, that we risk shame at Messiah’s coming if we don’t “abide in him”—that is, if we don’t stay in community with Messiah and his people:

And now, little children, abide in him; that, when he shall appear, we may have confidence, and not be ashamed before him at his coming.28

In New Testament practice, we also bear our community’s shame even when we aren’t directly involved in causing it. Paul makes this point with rhetorical questions:

Who is weak and I’m not weak? Who is offended without me burning with shame?29

If we are ashamed either for our misdeeds or for another’s, however, it’s redemptive, as it was for Peter when the cock crowed after he had been disloyal to Jesus.30

Shame in God’s kingdom is at once communal, dreadful, and redemptive.

Christianity, then, offers no shield from shame. It's worth pointing out that while the New Testament expounds on Jesus's offer of redemption from sin, it nowhere promises a life free from shame. In fact, Paul even accepts as appropriate his readers’ present shame for their past, forgiven sins: "Therefore what benefit were you then deriving from the things of which you are now ashamed?"31

In God's kingdom, God and Jesus can suffer shame, too

The kingdom of God is a public realm, a community in which Jesus himself can experience shame. The book of Hebrews points out that those fallen away from discipleship “again crucify to themselves the Son of God and put Him to open shame.”32 Unfortunately, then, we can shame Jesus. And like Jesus, God can suffer shame in this community: if Jesus’s followers fail to seek a “better country,” God can be “ashamed to be called their God.”33 This “better country” is a just community—the kingdom of God.

Like us, God and Jesus live in community. If they can suffer shame, we can, too.

Shame in one age is honor in the next — but the ages overlap

Of course, we live in two communities at once—one in this "present evil age"34 and the other in the age to come, which began at Jesus's crucifixion. At that moment, the present age gave Jesus the most shameful death possible. But dying on the cross, Jesus also expected joy in the age to come.35

As a member of two communities—broadly speaking, the present age and the new creation—we also can experience both shame and joy from the same circumstances. In Acts, for instance, the apostles, after being beaten, left the Council “rejoicing that they had been considered worthy to suffer shame for His name.”36 They suffered shame as members of Jerusalem’s present community, but they experienced joy as members of God’s now-and-future kingdom.

In this time of overlapping political ages, shame in one age is honor in the next—and often at the same time.

Political shame brings community, but only the community remains

Shame is clearly a negative emotion, and we don’t want to shame God or be ashamed ourselves. But in a way, the very possibility of shame suggests a community, and the realization of even misguided shame from a broken community—as, for instance, Jesus’s experience of his community’s shame on the cross—can help make an alternative community possible.

Shame isn't the end. It's the beginning. Hannah Arendt points out that both the Hebrew and Roman origin stories involve shameful acts: “Cain slew Abel, and Romulus slew Remus . . . in the beginning was a crime . . .”37 Likewise, our country's origin story involves the crimes of slavery, dispossession, and genocide. But if we accept the shame that Montgomery's lynching memorial and similar gallant public spaces foster, we can begin again.

The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

“Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” Equal Justice Initiative, 2017, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/.

Acts 26:26 KJV.

Quoted in Neiman, Learning from the Germans, 269.

Smith-Christopher, Biblical Theology of Exile, 122.

Leviticus 26:40-42 NNAS.

Smith-Christopher, 121. Emphasis in the original.

Smith-Christopher, 105-123.

Daniel 9:8, quoted in Smith-Christopher, 118.

Ezra 9:6-7, NNAS.

Stearns, Shame, 37.

Brett, Political Trauma and Healing, 149. While describing the advantages of Native American tribal religions’ “social shame,” Vine Deloria, Jr. makes the same distinction between guilt as personal and shame as social. Deloria, “Christianity and Indigenous Religion,” 156.

Arendt, Responsibility and Judgment, 147.

Arendt, 150.

Eliot, “Little Gidding,” 56-57, lines 192-195. In his Discourse on Method, Theodor W. Adorno makes a similar observation: “It is in the nature of the defeated to appear, in their impotence, irrelevant, eccentric, derisory.“ Quoted in Wolin, “From Vocation to Invocation,” 34.

Proverbs 14:34 NNAS.

Brown, Atlas of the Heart, 134.

Brown, 135-40, 146.

E.g., 1 Corinthians 11:22; Hebrews 12:2.

Smith-Christopher, 120-21.

Smith-Christopher, 121.

Elazar, Covenant & Polity, 356.

Elazar, 29.

Elazar, 91.

Smith-Christopher, 122.

Horsley, You Shall Not Bow, 14; Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness, Pts. 1 & 2, 405-406.

Royce, Problem of Christianity, 139.

Wright, 405-406.

1 John 2:28 KJV.

2 Corinthians 11:29 in Wright, Kingdom New Testament, 379.

Matthew 26:69-75.

Romans 6:21 NNAS.

Hebrews 12:6 KJV.

This is the inverse implied by Hebrews 11:16: “Instead, we find them longing for a better country, a heavenly one. That is why God is not ashamed to be called their God; for he has a city ready for them” REB.

Galatians 1:4 NNAS.

Hebrews 12:2.

Acts 5:41 NNAS. Likewise, in his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus counsels us to rejoice when we’re shamed by persecution or false accusations. Matthew 5:11-12.

Arendt, On Revolution, 10.