Public space wants place

Civil Rights icon Jim Lawson, who died Sunday, had an urban designer's vision

The 1961 Freedom Riders movement created public spaces on buses. The movement did it by seating Black and white movement members together on several commercial buses traveling into the Deep South. The riders wanted to see if the Southern states would honor a 1946 U. S. Supreme Court ruling, Morgan v. Virginia, that found "whites only" seating on interstate bus transit unconstitutional.

The states didn’t honor the ruling, but the movement was successful anyway. Many of the movement’s riders were assaulted and jailed, but the publicity pressured the Interstate Commerce Commission into enforcing Morgan v. Virginia with specifics and deadlines that the original court ruling had lacked.1

The Freedom Riders movement's chief architect, Jim Lawson, died Sunday at the age of 95. He died unsatisfied with the movement’s success. According to historian Raymond Arsenault, Lawson realized that the Freedom Riders “ultimately failed in their effort to bring the nation, or even most of the civil rights movement, into the confines of the ‘beloved community.’”2

Public space as precursor to political place

Public space, such as the 1961 racially integrated bus trips, presents itself as a precursor. When public space appears, so does the promise of a physical, political place—Arsenault's "confines of the 'beloved community.'" As it did for Lawson, the presence of that promise sometimes outweighs the space that carries it.

Rev. James M. Lawson Jr., who died Sunday at age 95, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Hannah Arendt may have been the first to recognize the distinction between public space and political place:

This public space of adventure and enterprise vanishes the moment everything has come to an end, once the army has broken camp and the "heroes"—which for Homer means simply free men—have returned home. This public space does not become political until it is secured within a city . . . This city, which offers a permanent abode for mortal men and their transient deeds and words, is the polis; it is political and therefore different from other settlements . . .3

Politically, we’re back in the days of Homer, or at least Arendt’s Homer, in which people dare to create public space, but the political places these spaces point to haven’t returned.

In fact, what today passes for politics closes its doors to this promise of political place. We can see the outlines of this promise, though, when citizens, acting outside the closed doors of oppressive power structures, by faith create public spaces and instantiate justice.

Illustration of a public plaza in Camillo Sitte’s 1889 book The Art of Building Cities.

These doors aren't always figurative. If "public" buildings are an assertion of present power and private wealth, then the spaces among these buildings created by the buildings' outlines can represent another kind of power, a citizenry speaking and acting as political people.

Tearing down “the geography of insurrection”

The spaces among buildings in cities have become less hospitable to citizens speaking and acting in public. Starting with the early-modern penchant for street grids and the elimination of recessed spaces, modern city planners became less concerned with public spaces than with the buildings whose outlines were used less and less to create those spaces.

To my knowledge, the nineteenth-century urban theorist Camillo Sitte was one of the first moderns to argue for the renaissance of irregular, recessed spaces found among buildings in ancient and medieval cities. These irregularities, he thought, would create recesses away from the general flow of traffic:

That would bring about numerous recesses, partially symmetrical, and open spaces removed from traffic where monuments and statues might be advantageously situated.4

Sitte believed also that churches and other central buildings should retain the ancient and medieval practice of adjoining other buildings for the sake of the resulting public squares and other public spaces.

The modern preference for standalone churches is bad enough, Sitte thought, but he seems to have been more exercised about the modern tendency to build cities mostly in a series of rectangular blocks:

Modem streets, like modern plazas, are too open. There are too many breaches made by intersecting lateral streets. This divides the line of buildings into a series of isolated blocks, and destroys the enclosed character of the street area.5

Sitte’s concerns focused on aesthetics, but James C. Scott found a political motive in these same modern shortcomings. In his 1998 book Seeing Like a State, Scott celebrated the medieval complexity of some cities’ street patterns, including that found in Bruges at the turn of the sixteenth century:

Streets, lanes, and passages intersect at varying angles with a density that resembles the intricate complexity of some organic processes. . . . The cityscape of Bruges in 1500 could be said to privilege local knowledge over outside knowledge, including that of external political authorities. It functioned spatially in much the same way a difficult or unintelligible dialect would function linguistically.6

By contrast, the modern street grid pattern, Scott found, was politically motivated to break down "the geography of insurrection."7 The effect of modern urban planning choices, Scott said, "was to design out all those unauthorized locations where casual encounters could occur and crowds could gather spontaneously."8

“Figure-ground” theory can reify political places

When Scott’s book shifts from Europe to South America, it examines utopian city planning. What would moderns do if they could start from scratch, as they did in Brasilia? Instead of building traditional Brazilian public squares and fostering crowded streets, Scott said, Brasilia created "sculptural masses largely separated by large voids, an inversion of the 'figure-ground' relations in older cities."9

Figure-ground theory, celebrated by Sitte (without the modern nomenclature) for fostering some of the ancients’ aesthetic choices, holds that "the space that results from placing figures should be considered as carefully as the figures themselves," according to Matthew Frederick.10 In other words, when urban designers work with buildings, they should make choices based on the spaces those buildings make with trees, walls, other buildings, and anything else within the subject buildings’ vicinity.

Like block design, figure-ground theory is as political as it is aesthetic, and for the same reason: we tend to dwell—even when we are outside—in positive spaces, that is, in spaces with "a defined shape and a sense of boundary or threshold between in and out."11 If you want urban people to gather outdoors, you follow figure-ground theory by creating positive spaces.

These positive spaces suggest a place. They might suggest Jim Lawson's and Martin Luther King's beloved community. Frederick believes this use of space to establish place is the chief end of good urban design:

An urban designer's primary responsibility is the design of physical space. However, a designer's ultimate goal is that the space be beloved by its users as a place. A space is a physical environment; a place is a space to which people have a personal attachment. Over decades and centuries, this attachment alters and enriches a space.12

The urban designer works for something like the same movement from space to place that Arendt describes in the movement from public space to political place. For both, the right space brings the hope of place.

If buildings can act as an assertion of present power and private wealth, then the spaces among buildings created by the buildings' outlines can represent another form of power, a power in a kind of future-is-now place where citizens speak and act as political people.

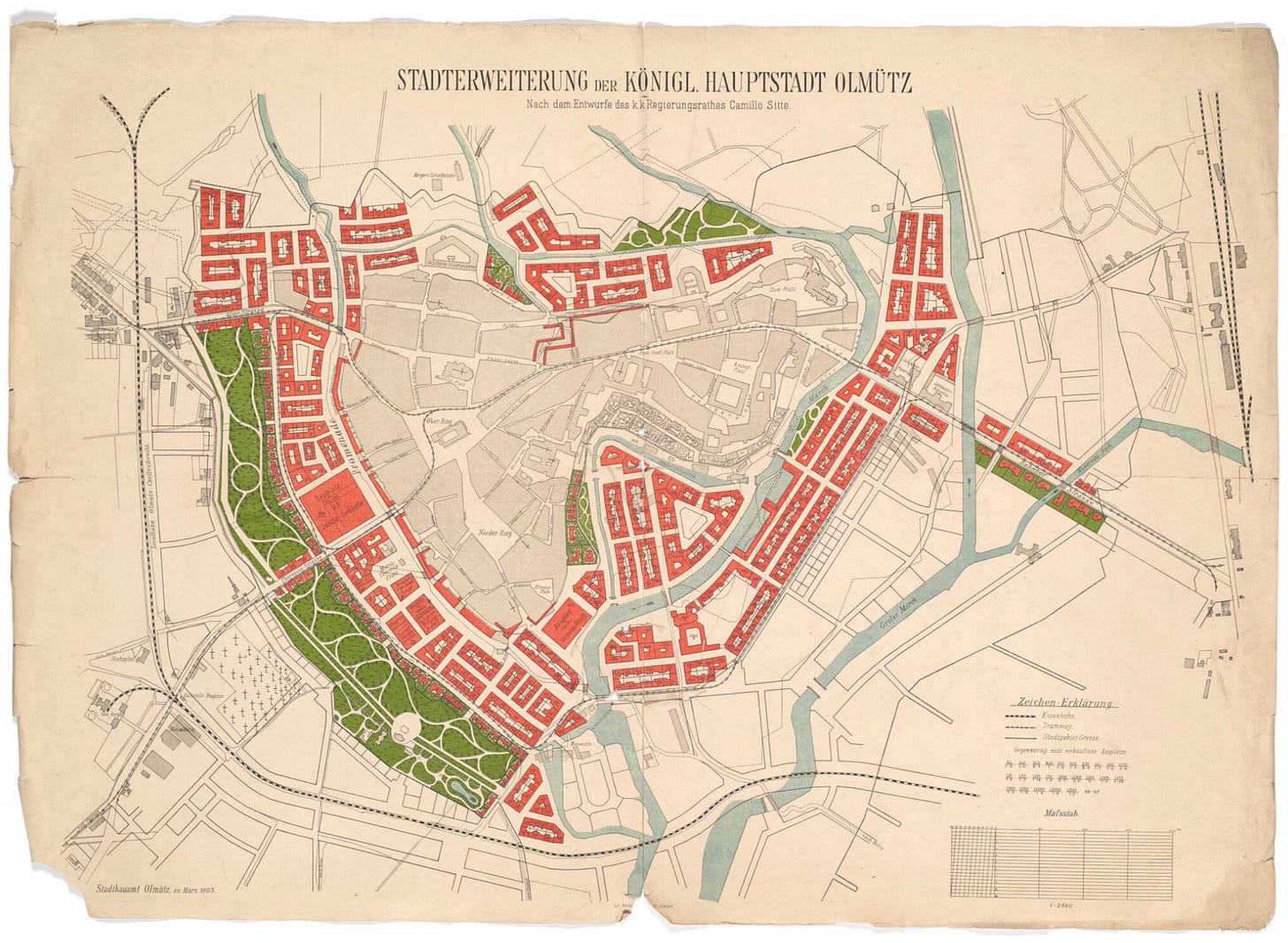

Camillo Sitte’s 1895 design “Extension Plan for Royal Capital City of Olomouc.” Note the irregularities and positive spaces in some of the red portion of his proposed plan.

Figure-ground theory and fugitive democracy

Figure-ground theory suggests something about democracy itself. Democracy’s power isn't exercised in the buildings meant to contain it. Political theorist Sheldon Wolin was right: democracy is always "fugitive"; it hasn't found a home. Wolin came to believe that democracy isn't a form of government and that "the idea of a democratic state is a contradiction in terms."13 Democracy is too much like Arendt’s concept of public space—a space created by speech and/or action that occurs episodically—to be mischaracterized as a form of government:

. . . any conception of democracy grounded in the citizen-as-actor and politics-as-episodic is incompatible with the modern choice of the State as the fixed center of political life and the corollary conception of politics as continuous activity organized around a single dominating objective, control of or influence over the State apparatus.14

For Wolin, democracy has little to do with the State. Democracy is about "originating or initiating cooperative action with others."15

Jim Lawson after his arrest during the 1961 Freedom Riders movement.

Four years ago, Jim Lawson, then 91, braved the Covid epidemic to speak at the funeral of another Civil Rights-era icon, Congressman John Lewis. That day, the New York Times published Lewis's last testament, part of which echoes Wolin's conception of democracy:

Democracy is not a state. It is an act, and each generation must do its part to help build what we called the Beloved Community, a nation and world society at peace with itself.16

Democracy doesn't seek a utopia (e.g., Brasilia), which is an inherently authoritarian dream. Instead, it seeks a beloved community. Like the fugitives in Hebrews 11,17 democracy seeks a city, one made up of people as living stones,18 a polis "whose architect and builder is God."19

The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Arsenault, Freedom Riders, 439.

Arsenault, 512. Arsenault concludes the final chapter of his book Freedom Riders with this observation: “And for some, even legal triumph and racial desegregation would bring little satisfaction as long as the beloved community remained an unrealized ideal.” Arsenault, 476.

Arendt, Promise of Politics, 123.

Sitte, Camillo. The Art of Building Cities City Building According to Its Artistic Fundamentals. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 2013, 34. Theo Mackey Pollack summarizes part of why Sitte favored irregularities: Sitte believed that “. . . irregularity gave character to public space and created an air of mystery that encouraged exploration; that street walls worked together to form spaces that could best be understood as outdoor rooms . . .” Pollack, Theo Mackey. “Camillo Sitte in the 21st Century.” Substack newsletter. LegalTowns (blog), May 28, 2024. https://legaltowns.substack.com/p/camillo-sitte-in-the-21st-century.

Sitte, 55.

Scott, Seeing Like a State, 53-54.

Scott, 61-63.

Scott, 121, 125.

Scott, 120-21.

Frederick, 101 Things Architecture, 3.

Frederick, 5, 6.

Frederick, Matthew, and Vikas Mehta. 101 Things I Learned in Urban Design School. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2018, 95.

Wolin, Sheldon S. “Contract and Birthright.” In The Presence of the Past: Essays on the State and the Constitution, 137–50. The Johns Hopkins Series in Constitutional Thought. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1990, 149-50.

Wolin, Sheldon S. “Fugitive Democracy.” In Fugitive Democracy and Other Essays, 100–113. edited by Nicholas Xenos. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016, 111.

Wolin, “Contract and Birthright,” 150.

Lawson, James M. Revolutionary Nonviolence: Organizing for Freedom. Edited by Michael K. Honey and Kent Wong. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2022, 15.

Hebrews 11:13.

1 Peter 2:5 NNAS.

Hebrews 11:10 KJV.

Interesting ideas, Bryce. I restacked with a note about churches becoming Meeting Houses again. How do we open more public space through the arts, forums, places to sit and contemplate?