Public space and politics

Introduction post 8 of 10

Good morning! Why does the creation of public space lead to “longing for a better country”? Why does Hebrews 11 celebrate both those who “overthrew kingdoms, established justice” and those who “were tortured to death”? The answers come by distinguishing between public space and political place, as the heroes of faith did. To access the other posts that make up the introduction to Political Devotions, click its subtitle’s post number: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

God’s kingdom irrupts in public space, but his kingdom is established in politics. One might say that, when a political foundation is laid, public space becomes a public place. Politics, strictly speaking, happens when public space is secured within a community, such as in a council, a ward, a village, a city or a country. Arendt makes this distinction between public space and political place:

This public space does not become political until it is secured within a city, is bound, that is, to a concrete place that itself survives both those memorable deeds and the names of the memorable men who performed them and thus can pass them on to posterity over generations. This city, which offers a permanent abode for mortal men and their transient deeds and words, is the polis . . .1

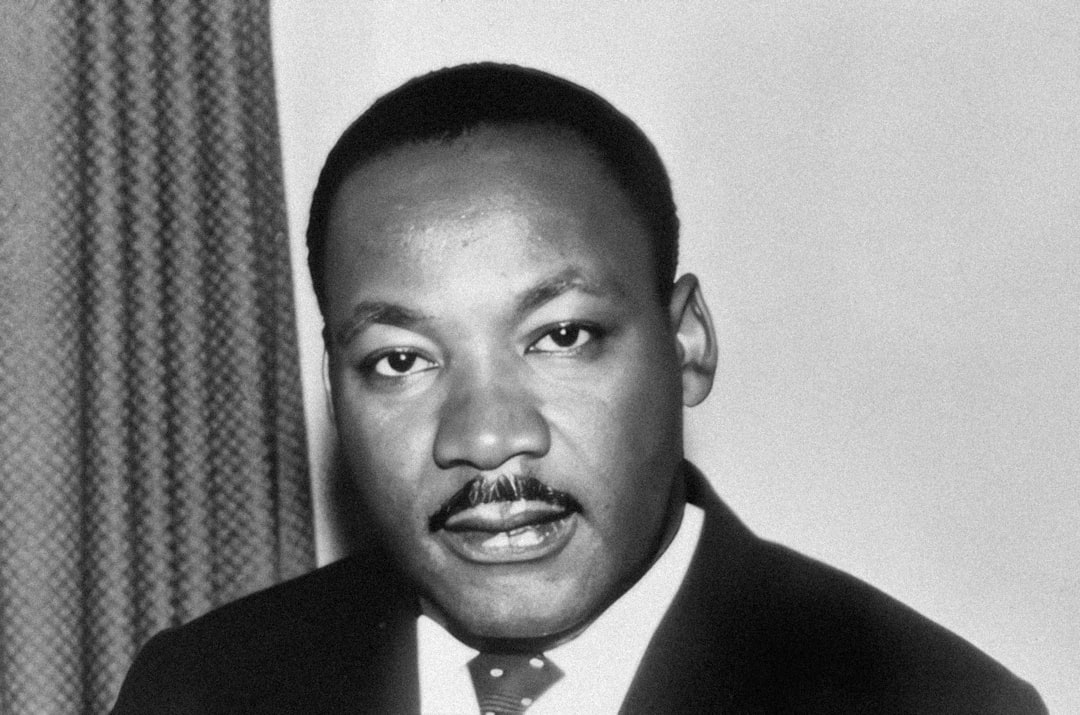

This distinction between public space and politics helps to make sense of Martin King’s lamentation on a joyful night. He and his followers created public space by successfully boycotting segregated buses, but King lamented that the Beloved Community didn’t materialize with that public space.2 This is also the dream of those heroes of faith in Hebrews 11 who created public space but longed for God’s politics on earth:

. . we find them longing for a better country, a heavenly one. That is why God is not ashamed to be called their God; for he has a city ready for them.3

This heavenly city, new Jerusalem, won’t stay in heaven. Jesus says that new Jerusalem “comes down out of heaven from my God.”4

The distinction between public space and politics suggests that the results of public action aren’t as important as the action itself. The varying results of faithful action described in Hebrews chapter 11, for instance, have no bearing on the reward for that action. Some women and men “overthrew kingdoms, established justice” while others “were tortured to death” or “were sawn in two, they were put to the sword, they went about clothed in skins of sheep or goats, deprived, oppressed, ill-treated.” Those who succeed as well as those killed or otherwise persecuted have “a city ready for them.”5 Doing justice is the important thing. The results don’t matter as much as the city, “whose architect and builder is God,” and the world to which that city comes.6

Each church is called to serve, in both similar and distinct ways, as this city’s prototype.7 When it’s functioning the way it’s created to function—as “the fullness of him who fills all in all”—a church becomes a prototype of God’s Beloved Community, God’s kingdom come. Paul understands the church as the praxis for new creation, for the kingdom of God in its fullness.8 That’s why his letters to the churches encourage unity and faithfulness to covenant. That’s why in fulfilling its calling, the church is inherently subversive of empire and other ungodly governments. The more the church functions as the kingdom of God, the more it will draw persecution even when it doesn’t engage the political structures of this age directly.

The church, though, is just one proleptic account of God’s kingdom. The Lord answers the Lord’s prayer—“Your kingdom come”—with all kinds of amateurs.

This is the eighth of ten posts that make up the book series’s introduction. Click here to read the next one.

Arendt, “Introduction into Politics,” 122-23.

Marsh, The Beloved Community, 1.

Hebrews 11:16 REB.

Revelation 3:12 NNAS. See also Revelation 21:2.

Hebrews 11:16, 32-39 REB.

Hebrews 11:10 REB.

The church is supposed to teach God’s wisdom—presumably true political theory—“to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly realms.” Ephesians 3:8-10 REB.

N. T. Wright finds this understanding in Colossians, for instance: The “divine presence” in the church in Colosse “is part of what [Paul] means in Colossians 1:27: The Messiah in you, the hope of glory. The indwelling Messiah, living in his Temple in Colosse, was the sign that ‘the hope of glory’ was starting to come true – the hope, that is, that YHWH would return in glory to his Temple, and that he would thereby fill the whole earth with his knowledge and glory, with his justice, peace and joy. Paul sees each ekklēsia as a sign of that future reality.” Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness (Vol. 1), 437.