My father suffered the seeming misfortune of siring, as my parents’ firstborn, his father, a bookish man—luftmensch is the term I use for him and me—a man who moved through careers maybe as often as cicadas molt.

We kids would pluck their crispy, brown skins from our Tidewater pines’ trunks, and we’d slyly stick the skins on one another’s shirts and sweaters. Exoskeletons, though, even bug-eyed ones, usually were no scarier than the replica human skeletons that hung later in our biology classrooms and haunted houses. And when I’d change careers, my father would never lose his equanimity; he’d quietly support me.

I practiced law right out of school for sixteen years. My father practiced law right out of school, too, but he stuck with it, and he ended up on the circuit court, our state’s court of jury trials. When he reached the mandatory retirement age of 70, his fellow judges threw him a celebration dressed up as a judicial hearing.

A jury of Pop’s peers—robed judges—filled the box’s fourteen chairs. Lawyers and family occupied the benches beyond the rail. Sitting there, I thought of the Episcopal Church that my parents attended—the robed clergy and choir, the communion rail, and the well-dressed laity, with our family always seated on the Epistle side, in a second-row pew. Pop learned to lie down in the green pastures of his era’s great institutions—marriage (64 years!), the church, the courtroom.

Above: Pop at court, nearing his “retirement”

Granddaddy, though, lived in times more like our own, an era less friendly to institutions. During the Great Depression, he made a living closing banks. He and my grandmother divorced while Pop was in law school. Granddaddy had started right where I ended, teaching high-school English. My grandmother, one of his students, was quite taken with him, and she quit college after one year to marry him.

The officiant, Judge Bowman, roasted Pop from the bench. He described Pop’s way of orienting each criminal defendant to his courtroom. Pop would introduce the defendant to the Commonwealth’s attorney, the bailiff, the clerk, the court reporter, and even the courtroom’s previous judges, dead and depicted in the portraits hanging from the courtroom’s walls. For Pop, due process was grounded in hospitality and respect.

When Judge Bowman was done, Pop spoke. He started by introducing the assembled to each judge hanging from the walls. At first I wondered: hadn’t he heard Judge Bowman? Was he being ironic? Yes and yes, but he was mostly being Pop: fastidious, gracious and procedural. Everyone got the same treatment.

At 70, Pop still had plenty in the tank, so the ceremony didn’t really mark his retirement. He was only leaving his hometown courtroom, which at his age he had to surrender. He began substituting for judges all over the state three to five days a week until his hearing began to fail him at age 89. At his retirement ceremony, we heard highlights and whimsy from a career that wasn’t half done.

Growing up, my siblings and I used to beg Pop to show some of the family movies. We’d watch Granddaddy on vacation at around 60 years old, floating endlessly on his back in the Atlantic Ocean. He was probably asleep. How did he do it? My father rarely talked about his upbringing or his father. But his choices not to stop the camera at the beach, not to edit the film at home (he owned a splicer), and not to privilege other reels on movie nights suggested to me that he felt some mix of admiration, horror, and ultimately acceptance regarding his father’s orientation to life.

I kind of floated through my teen years and college. I read ravenously and loved writing about what I read. (My recent post “Father Abraham’s Lit Crit” felt like glory days, a return to the critical essays I wrote almost weekly in school.) But exams, and even many classes outside the humanities, were often nuisances, and while I couldn’t avoid the former, I often skipped the latter.

I’m not exactly sure how I presented in those days to my father, but I have some idea from what felt then like his constant refrain: “You gotta get organized, boy.” My brother and I were given to understand that “boy” was how Pop’s uncles invariably addressed him, but the older I got, the more I took Pop’s injunctions personally, as if disorganization were something I couldn’t do much about. Pop wasn’t a teacher, but he expected those around him to develop the skills and character that made certain virtues, like organization, evident and habitual. Honestly, I didn’t get organized until I had to—that is, until I practiced law.

I was more like Mom. She’d sometimes look out a window and say to no one in particular, “I was born in the wrong age.” She was a history major, and her reveries would involve the English aristocracy before the rise of the gentry class. I was an English major, born in the wrong book. I admired Laurence Sterne’s slow, easily distracted Tristram Shandy, whose disorganized autobiography, written around the time and place of my mother’s reveries, didn’t get around to chronicling his own birth until volume three.

Tristram also lacked self-confidence. Thematically, his lack stemmed from his failure to meet the expectations of an ordered—but absurd, thankfully; the book is trenchant comedy—outside world. Like Tristram, I maintained a faith in a kind of impenetrable membrane between my word-fortified interior life and whatever it took to function adequately beyond it.

Saint Paul, whom I read as heroically externalizing a similar struggle, helped to draw me as a teen to the Charismatic movement. I left our family’s Episcopal church and, along with attending almost nightly Bible studies during summers, memorized a few chapters of Paul’s letters. When Paul told the Athenians that in Jesus “we live, and move, and have our being,”1 it felt to me like the assertion of an involved interior life against a recalcitrant exterior world. Paul, I came to think, was committed to breaking his membrane, to living out his ideas in public, and he often got stoned and beaten for it.

I wasn’t so bold, so I beat myself up instead. My first hint of this practice came during my first year after law school, which I spent clerking for a federal judge with whom my father had fixed me up. When the time came for my review, the judge wrote some nice things. In the space reserved for negative remarks, the judge wrote only, “Lacks self-confidence.” I finally had a label, and I resonated with it.

But earlier, one summer home from law school, I tried externalizing my inner Paul. I finally responded to one of Pop’s “organized” reminders. “I am organized, Pop, just on a higher level.”

Pop said nothing. But I wonder now if I had made him think again about his father, tanning the front of his hairy exoskeleton in the ocean.

Maybe Granddaddy had reached some higher level. He had his fiction published in the William and Mary Quarterly. Pop loved to tell the story of an English professor who, over his long career, improbably had taught both Granddaddy and Pop. One day the professor told Pop, with (as far as I could tell) unwarranted candor, “You’re not half the student your father was.”

I became a lawyer, though, because I had some of my father’s qualities. Pop, my two siblings, and I—all lawyers—all loved argument and reason, and my siblings and I learned from Pop to admire a kind of reason grounded in character and precedent. At the dinner table during our childhood, most of Pop’s stories amounted to either encomia or cautionary tales involving friends, relatives, or other lawyers. As we ate, the three of us imbibed something like what Montesquieu called “the spirit of laws.”

Of course, I had come to no “higher level,” and at age 25, as Pop and I sat in my apartment a few city blocks from the situs of my clerkship, I admitted to a lot of arrogance and told him that I loved him. After that day, I still preferred talking about abstractions and he about people. But our conversation became gradually easier.

Towards the end of my law career, I got a call one night from Pop. I wasn’t home, so he left a message. I was at the office preparing for what turned out to be my longest trial. I represented the plaintiff in a car accident case. My client had sustained only soft-tissue damage, but due to its extent and to a peculiarity in our state’s tort law, this case’s potential upside was greater than that of even the wrongful death case with which I was to later close out my legal career.

Though Pop wasn’t given to discussing abstractions, he loved bon mots—his or others’—for their wit and felicity. If just the right words failed him, however, he never compensated with loquacity. He simply got blunt.

The message on the answering machine was short. Pop concluded with, “You’re a damn good lawyer, Bryce. Give ‘em hell.”

When I heard the message later that night, I felt the wind shift. The next morning, I seemed to enter the courtroom with sails aloft and alow. We eventually won what then was the largest soft-tissue jury award in state history.

I’ve often reflected on the Patriarchs’ notion of blessing. Was Isaac, in giving Jacob the older son’s blessing, really as blind—or, more to the point, as gullible—as Genesis suggests? By the time Isaac was old, I think he knew that Jacob, described in the narrative as one who lived quietly, “dwelling in tents,”2 and not at all like his father, would find his own way.

Pop left that blessing on my answering machine over a quarter century ago. I since became an assistant pastor before following Granddaddy into the classroom. In all three professions and especially in my spare time, I’ve largely dwelt in my words—often in my journals, in the margins of books, and now also in this Substack.

A couple of years ago, my college roommates, now scattered from Maine to Texas, had our first reunion. One of them told the rest of us and our spouses about his outstanding memory of me: “All hell would be breaking loose in the house, but Bryce would be slouched in a chair, reading a book as if his life depended on it.” I had forgotten that.

I loved lawyering, pastoring, and teaching. But in a sense, my professions were background noise to my reading and writing. They were passing buildings and trees along the tracks my words and I traveled together. Retirement last year means I can travel this way more. But sometimes, after the sun sets and the trains’ windows begin reflecting my interiors, I’ve seen my self-doubts there, sharp as ever, stowaways from my previous professions.

Deflating memories return. One involves one of my own English professors, whom I approached for an explanation for the “D” he had given me on a paper.

“Because I was feeling generous,” he responded sharply. “Who taught you how to write?”

A few years back, at age 94, Pop died. He wasn’t around when I retired last year and finally gave myself up to research and writing.

We all grieve differently. Outwardly and initially, my grief work involved repeating, to my family but also to anyone who would listen, my father’s spoonerisms and his many twists and turns of phrase or of pronunciation (“Not a chonce” when the answer was no; “Leave us went” as our signal to go). These odd verbal bits served in his domestic life for the bon mots he reserved for more public occasions. Channeling his stock phrases still helps to bring him near as I process his passing.

So does talking to him. A deacon at his church—a dear family friend—suggested that I talk to him whenever I want to share an occurrence or a memory with him. This practice has helped to open another world to me. As my sister observed apropos of her own experience in grieving the loss of our parents, the membrane between the realms of the living and the dead is thinner than we may think.

Sometimes my parents seem to speak to me, too, usually through a memory or through some unusually forceful association. Or sometimes it happens when I read certain authors. Pop often seems present to me in the essays of James Baldwin and Ann E. Berthoff, both of whom were born the same year as Pop. Neither writer shared Pop’s—or my own—privilege in this white-male-dominated society. But all three of them loved justice and loved America enough to seek, in the Bible’s sense (and to borrow from the title to Baldwin’s mid-career novel), another country.

This past March, Pop also showed up in a poem. Poet Luisa A. Igloria’s “The Language of the Law,” one of her daily poems published on Via Negativa, speaks my truth about Pop and about his and my relationship with such specificity and force that I contacted Luisa and received her kind permission to republish it here. It reads like prose, like testimony:

Parents sometimes say things like I hope

you follow in my footsteps. Or at least,

my parents did. In my case, the hope was

law school, because my father was a lawyer

most of his life; then in the last twelve

or fifteen, a judge in the local circuit

court. I was in high school when he started,

and had learned to type. He was, however,

no good at it; but didn't think he should

ask any of the law clerks or secretaries

to type up his statements of decision. And so

at the end of the day on Fridays, he'd lug home

one of the office machines, a heavy Remington

Standard with a gunmetal frame and green keys,

and ask for my help. I loved the language of

the law— formal, latinate, nuanced— though I

didn't always understand everything such words

could mean: prima facie, incumbent; appellate,

plea, substantial evidence. We sat at the table

after dinner, my fingers ready to go while he

chewed on the end of a pencil as he reviewed

scribbles on a legal pad. Interviewers often

ask me how it happened that my daughters

became writers too; and how or if I'd pushed

them (that always gives me pause). How much

of our propensities— that bright quickening

to language, those qualities of dark brooding—

are passed down somehow in the blood? How much

is nurtured, willed, imposed; and how much accident,

a hand held out as if to say stop, that's not

what I intended? And it's true, we look to language

to help us regulate, to keep monarchs from corrupting

their powers, to give expression to both the seething

and the profound intimacies in our days. Not yet

a perfect arbitration by any means, but I think

there was a time when we said things like justice

and rights and recourse to the law for remedy or

relief, and it felt like we knew what these meant.

Tears, of course, the first few times I read this poem—the hot tears of deep connection.

More importantly than its uncanny encapsulation of the relationship between Pop and me, Luisa’s poem seems, from my point of view, to put the current administration’s attack on due process in the context of her father’s—as well as my father’s—character, values, and public labor.

But it wasn’t until that evening, while I was in the kitchen sautéing vegetables, that Pop reached through Luisa’s poem and spoke to me more directly. Some of the poem’s lines returned, and through them came my father’s heart. What he said startled me, the way unsurprising words can surprise us in a dream:

“You’re a damn good writer, Bryce. Give ‘em hell.”

More tears. Triumphant grief and realization.

Unlike his father, Pop wasn’t given to poetry. He liked to quote only one couplet as far as I recall. You’ll recognize it: “In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo.” I think Pop liked Eliot’s terse and implied critique of the women’s pretense. Eliot was of Granddaddy’s generation, too, and I wonder if Prufrock reminded Pop of him.

My own oft-quoted line from the same poem—again, no surprise—is “Do I dare to eat a peach?”

Okay, Pop, I will.

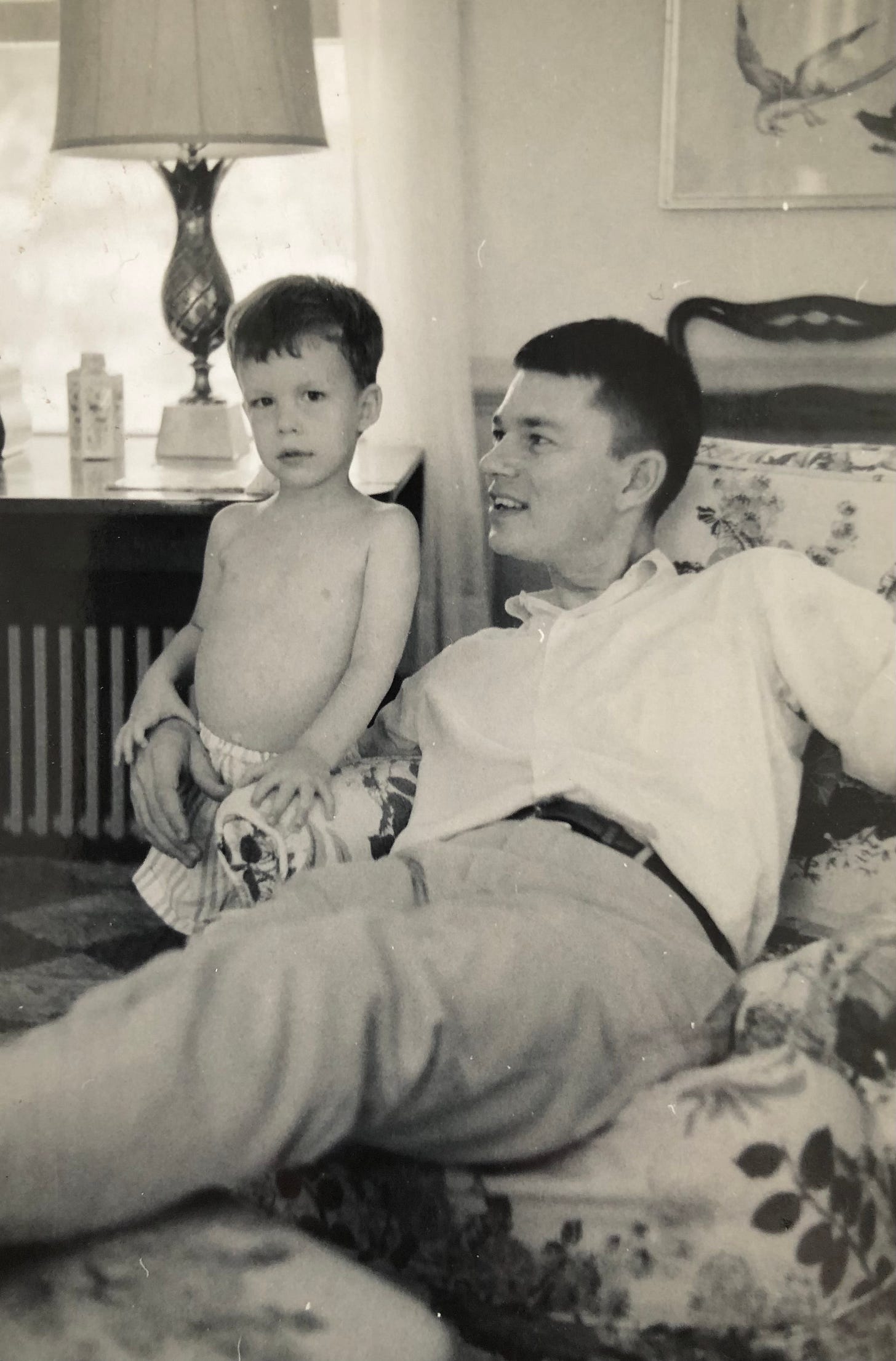

Above: Pop and I long ago. The short footnotes below refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Acts 17:28 KJV.

Genesis 25:27 KJV.

I can't tell you how much I love this piece, or how grateful I am to begin my day with it. We've known each other for a long time and yet there was so much here that was entirely new to me -- revealing, tender, appreciative -- and much that reminded me of myself. I hope we can talk more about these things someday. Thank you.

Years ago, a friend referred to his "crime of a happy childhood." Your memories remind me of my own father and his brief career as a member of the Texas Legislature (or the Ledge, as we Austin hippies later called it). And your father's little expressions around the house: I endlessly savor the way my dad would awaken me and my two sisters on Sunday mornings by strolling around and announcing in mock-military tones, "All right you men...Especially you new men."