Jesus as trickster

The oppressed get the gist . . . and the jest

Who has believed our message? And to whom has the arm of the LORD been revealed? — Isaiah 53:1 NNAS

Why do so many people doubt Jesus’s first miracle? It’s pleasing enough: he turns water into wine. Perhaps producing wine for some drunk partiers seems too gratuitous for a serious Messiah. But the Hebrew Bible’s prophets use wine to speak of the coming days of Messiah.1 Jesus’s miracle and its wedding-feast setting suggest that Messiah and his last days have finally come.

These Messiah prompts also pervade the miracle’s lead-up and follow-up. Jesus’s mother Mary approaches him with a simple observation: “They have no wine,” which may suggest Israel’s cry for its long-awaited Messiah. Mary’s observation suggests another theme, as Raymond Brown points out—the “barrenness of Jewish purifications.”2 After all, Jesus has the servants pour the water into “six stone waterpots set there for the Jewish custom of purification.”3 Jesus replaces Jewish purification water with Messiah’s wine, which makes the first miracle consistent with the theme of replacement/fulfillment developed early in John’s Gospel. In the Gospel’s first few chapters, Jesus also linguistically replaces Herod’s Temple with the temple of his body,4 and he foretells the replacement of worship at Jerusalem with worship “in spirit and in truth.”5 Jesus’s first miracle, therefore, fits into John’s Gospel thematically and theologically.

And of course, Jesus’s miraculous wine echos Elijah’s miraculously refilling pitcher of oil6 and Elisha’s miracles of supplying oil.7

I suppose that, even after being informed of these connections, many people would still doubt that Jesus turned the water into wine. Even people who accept Jesus’s other miracles as historical events, Brown points out, seem to want to doubt this one. So in his Anchor Bible edition of John, Brown defends the miracle’s account from the attacks many people have pitched against it.

But I wonder if the attacks stem from a more fundamental problem that Brown doesn’t address: John’s story itself gives two different accounts of the wine’s origin, only one of which is miraculous.

Here’s how the story’s two accounts diverge. When the servants fill the stone jars with water, Jesus tells them to take some of the resulting wine to the master of the wedding feast. John’s account gives no suggestion that anything Jesus says or does reaches the ears or eyes of anyone but the servants.

The master of the feast—and presumably the more sober and discerning wedding guests—leave the feast thinking that the bridegroom has, against good sense and apparent custom, saved his best wine for last. How would this good wine be appreciated? After all, by this time, most if not all of the guests are drunk. The servants, however, leave knowing that Jesus has produced this fine wine from water. We assume that the servants are also aware, as we are, of the miracle’s dramatic irony: only the servants, Jesus, Mary, and the Gospel’s readers know how the best wine came last.

Jesus’s first miracle presents what James C. Scott calls a “hidden transcript,” defined as “a critique of power spoken behind the back of the dominant.”8 The critique represented by the wedding account is not a damning critique: it involves (as many hidden transcripts do) the mere cluelessness of those in power. However, the first miracle’s Messianic hidden transcript foreshadows Jesus’s crucifixion, which, to use Scott’s language, is occasioned by one of “those rare moments of political electricity . . . when the hidden transcript is spoken directly and publicly in the teeth of power.”9 The council of elders asks Jesus if he is the Son of God—that is, the Messiah—and Jesus responds, “Yes, I am.”10 Jesus’s time has come. The hidden transcript is finally spoken directly, and the council immediately has Jesus crucified.

Historians historically have given little credence to hidden transcripts. Often, the hidden transcripts of the poor are verbal, handed down from generation to generation through marginalized communities, while the transcripts of the powerful are written and move through entire societies. These written transcripts, says historian Nell Irvin Painter, “the letters, speeches, and journals that historians have used as the means of uncovering reality and gauging consciousness ought more properly to be considered self-conscious performances intended to create beautiful tableaux.”11 The guests leave the wedding at Cana with such a tableau of the bridegroom’s performance.

As soon as Jesus turns the water into wine and “revealed his glory,” as John puts it,12 Jesus reveals a divide. The wedding’s servants failure to contradict their masters’ account reveals the “great gulf,” as Jesus later puts it, between the rich and powerful, on one side, and the poor and powerless, on the other, in the Gospels’ world.13 The servants’ silent complicity with Jesus suggests also, at the outset of Jesus’s ministry, which side of the gulf is more likely to accept and celebrate the gospel of God’s kingdom.

Sometimes we may misunderstand Jesus because we don’t have sufficient historical and cultural context, the kind of context that Brown’s commentary can offer us on various points. We get enough background from Brown to make sense of Jesus’s first miracle that might otherwise seem like a harmless dry run (pardon the pun) of a miracle-working prodigy.

But sometimes we may misunderstand Jesus because we assume his words and actions may be taken as plainly as we would take the words and actions of people in power.

Jesus isn’t in power, though. Like the marginalized who seek public space, Jesus’s public life involves navigating between the Scylla and Charybdis of compliance and defiance. Scott’s description of the subtle public spaces marginalized groups find fits Jesus’s context:

Most of the political life of subordinate groups is to be found neither in overt collective defiance of powerholders nor in complete hegemonic compliance, but in the vast territory between these two polar opposites.14

Most of the Gospel text occupies this “vast territory.” We admire Jesus in this element because, to borrow from Scott again, Jesus “dares to preserve as much as possible of the rhetorical force of the hidden transcript while skirting danger.”15 Scott seems to explain Jesus’s hard-won reputation for subtlety as he parries questions put to him by the powerful religious leaders compromised by their connections to Caesar:

If subordinate groups have typically won a reputation for subtlety—a subtlety their superiors often regard as cunning and deception—this is surely because their vulnerability has rarely permitted them the luxury of direct confrontation. The self-control and indirection required of the powerless thus contrast sharply with the less inhibited directness of the powerful.16

We admire Jesus’s “self-control and indirection,” but we also may misunderstand some of his sayings because we assume he’s speaking with the “less inhibited directness of the powerful.”

Sometimes our misapprehension of Jesus’s message may come from both insufficient historical context and an unrealistic expectation of forthright speech. For instance, we may read Jesus’s direction to “pay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God” anachronistically, as a slogan for separating our political and spiritual lives.17 Historically speaking, no such division was conceived of in the first-century Jewish world beyond the compartmentalizing practice of the compromised religious leaders.

A “more subtle” reading is available, N. T. Wright believes.18 It starts with context. The Pharisees and Herodians’ question to Jesus—“Is it lawful to give a poll-tax to Caesar, or not?”—was a test of Jesus’s revolutionary bona fides. The coin the Pharisees produced at Jesus’s request was blasphemous, proclaiming Caesar to be the son of a god.19 Finally, Judas the Galilean had recently led a revolt, claiming that paying taxes to Caesar was a denial of God’s kingship over Israel.20

With this recent revolt, the “more subtle” reading of Jesus’s “Give to Caesar” response involves both context and Jesus’s need to navigate between compliance and defiance. Judas the Galilean’s revolt was modeled after the uprising of Judas the Maccabaean, who followed Matttahias’s dying words: “Pay back the Gentiles in full, and obey the commands of the law.” Wright finds in “Jesus’ cryptic saying” an allusion to this direction, read annually during Hanukkah—“a coded and subversive echo of Mattathias’ last words.”21 Pay Caesar back for what he has done to us! The result was subtle, Wright says:

Had he told them to revolt? Had he told them to pay the tax? He had done neither. He had done both. Nobody could deny that the saying was revolutionary, but nor could anyone say that Jesus had forbidden payment of the tax. Jesus the Galilean envisaged a different sort of revolution from that of Judas the Galilean.22

Jesus’s point seems to be his “different sort of revolution,” the messianic replacement of purification rituals, Temple, and Jerusalem itself with new creation and public space that the wedding-feast miracle and the rest of John’s early chapters point to.

A straightforward Jesus, on the other hand, who demands the separation of church and state would be out of this historical and political context. A straightforward Jesus would also negate his statement’s narrative context, as Richard Horsley points out: “. . . if Jesus’ questioners and listeners all assumed such a separation of Caesar and God into utterly separate spheres, then how could the question have possibly been part of a strategy to entrap Jesus?”23

It’s hard not to read Jesus’s contextualized, subtle answer to the either/or tax question without a smile of appreciation. We also sense a kind of restrained humor in his answer as well as in the wedding-feast narrative. Perhaps the subtlety and humor come from Jesus’s role as a kind of trickster. Jesus seems to side with the silent, politically weak servants, and he seems to know something that the more honored guests don’t know. According to Scott, the trickster’s knowledge of the powerful makes up for his own lack of power:

The trickster is unable, in principle, to win any direct confrontation as he is smaller and weaker than his antagonists. Only by knowing the habits of his enemies, by deceiving them, by taking advantage of their greed, size, gullibility, or haste does he mange to escape their clutches and win victories.24

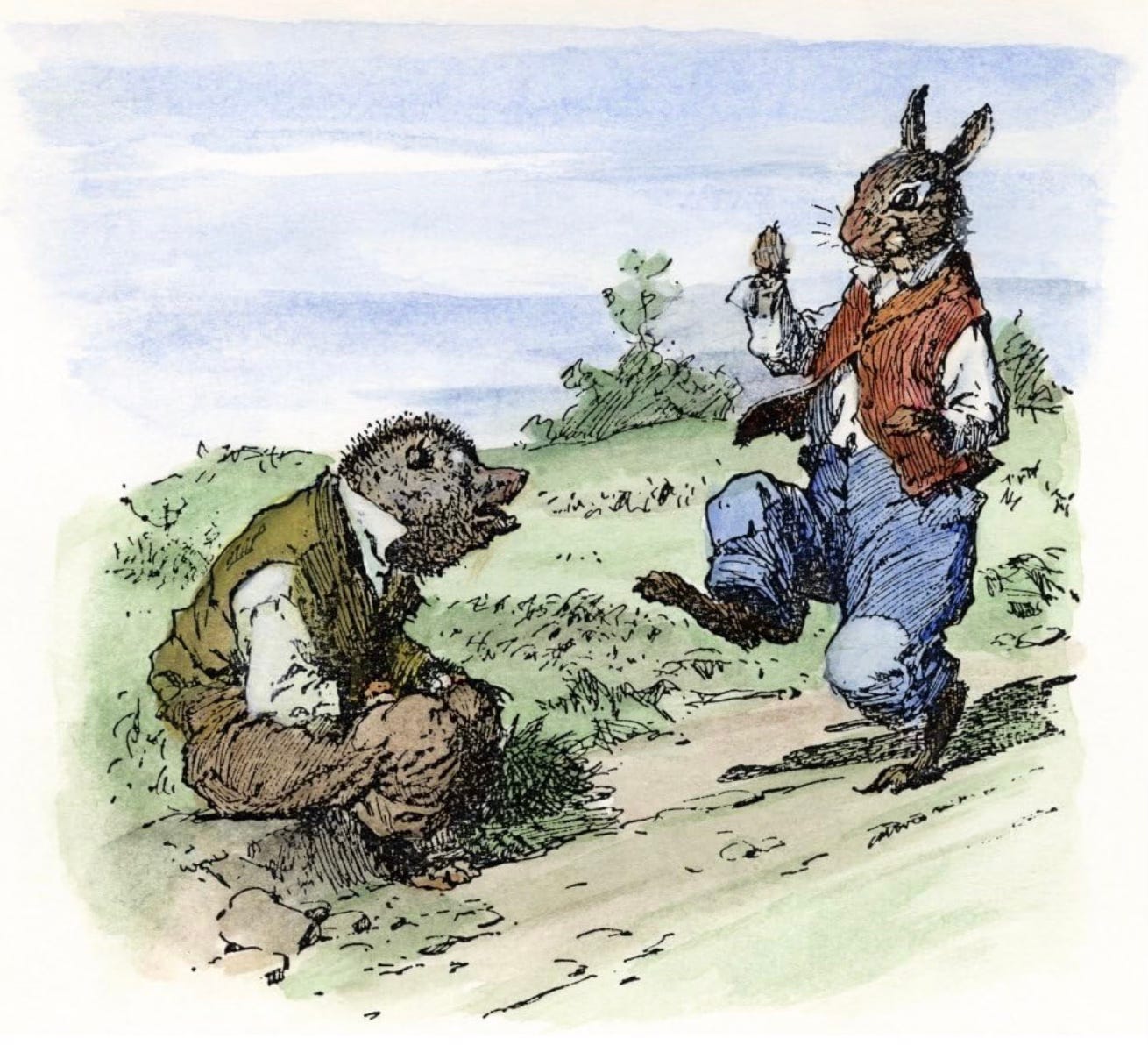

Scott examines the tales of Brer Rabbit, that legendary trickster, spoken among North American slaves, and he quotes Alex Lichtenstein about one of Brer Rabbit’s frequent, small victories in the public sphere: “Significantly, one of the trickster’s greatest pleasures was eating food he had stolen from his powerful enemies.”25 Jesus’s pleasure, though, seems to come from quite a different trick—secretly serving the best wine to the feast’s powerful and already sated guests, who would never appreciate its superior quality.

Jesus the trickster doesn’t take from the oblivious powerful. Instead, he gives to them without their knowing it. Likewise, Jesus the revolutionary doesn’t fight to defeat Israel’s enemies. Instead, he uses nonviolence to defeat them. Paul says that Jesus’s killers were, in a sense, tricked:

None of the powers that rule the world has known [God’s hidden] wisdom; if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.26

Encountering Jesus’s words and actions as the public performance of hidden transcripts often gets us closer to Jesus’s message. But Jesus as a generous trickster and as a nonviolent revolutionary doesn’t follow the standard means of subtly asserting hidden transcripts in public. Jesus overturns the expectations, then, of not only the politically strong but also of his friends, the politically weak.

Judging from the Gospels, though, the politically weak sure catch on faster. Jesus’s first miracle, then, gives us a hermeneutic: to understand the Gospels, find the oppressed’s side of the gulf.

After his death, Jesus’s story diverges again. The soldiers witness the earthquake and the angel, but the chief priests bribe them to say that the disciples stole Jesus’s body while the guards had been sleeping. This official account of the empty tomb, which Matthew says was widely circulated,27 contradicts the transcript of Jesus’s powerless disciples—their account of Jesus’s resurrection.

Jesus’s public career therefore ends the way it begins—with conflicting accounts, one by the powerful, and one by the powerless. The hermeneutical and political effects of these divergent accounts at both the beginning and end of Jesus’s public life seem to persist today.

Above: Uncle Remus 1895 Brer Rabbit and Brer Possum pen-and-ink drawing by Arthur Burdett Frost for the second edition of The African American Folktale by Joel Chandler Harris 1895.

The short footnotes below refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Brown, Gospel According to John, Vol. 1,105. See, e.g., Jeremiah 31:12, Joel 2:24-25.

Brown, 105.

John 2:6 NNAS.

John 2:18-22.

John 4:20-24 NNAS.

1 Kings 17:1-16.

2 Kings 4:1-7.

Scott, Domination and the Arts, x. “Transcript” doesn’t refer to a typed record of something verbal but to “a complete record of what was said. The complete recored, however, would also include nonspeech acts such as gestures and expressions.” Scott, 4n1.

Scott, xiii.

Luke 22:66-70 NNAS.

Painter, Southern History, 35.

John 2:11 REB.

Luke 16:19-26 REB.

Scott, 136.

Scott, 165.

Scott, 136.

Richard Horsely summarizes this anachronistic reading: “Assuming the separate of ‘church and state’ in antiquity, Jesus’ response to the Pharisees about the tribute to Caesar was interpreted as his injunction to render taxes due to the state, in the political sphere, and to render the worship due to God, in the religious sphere.” Horsley, You Shall Not Bow, 6. Like most moderns, political science professor Stuart A. Cohen accepts this reading of Jesus’s remark uncritically, though he correctly points out that this formula cannot “be accepted as a relevant paradigm for the Jewish perspective on the separation of powers.” Cohen, “Concept of the Three Ketarim,” 32-33.

Wright, Jesus and the Victory, 503.

Wright, 503.

Horsley, Jesus and Empire, 41-42.

Wright, 504.

Wright, 504-5.

Horsley, 12.

Scott, 162.

Scott, 162-63.

1 Corinthians 2:7-8 REB.

Matthew 28:11-15.

Or can it be taken very literally, he turned (a jug or more) of water into (the flasks of) wine, thereby making (more) wine? Late into the celebration the appearance of extra wine to soused partiers would be praised indiscriminately, hey thanks this is the best wine.

Brown, Wright, Scott, even Brer Rabbit woven into John’s Cana story! You go beyond the usual symbolism of abundance or messianic fulfillment into the political and rhetorical subtleties of hidden transcripts. The miracle is not deception but disclosure. Jesus “revealed his glory,” even if only a few saw. That tension between concealment and revelation edges toward what some have called the gospel as comedy—truth arriving in irony, surprise, and reversal, first grasped by the powerless. - Thanks, Bryce!