How to renew America's covenants

Follow Lincoln, who takes Paul's slant on three similar covenants

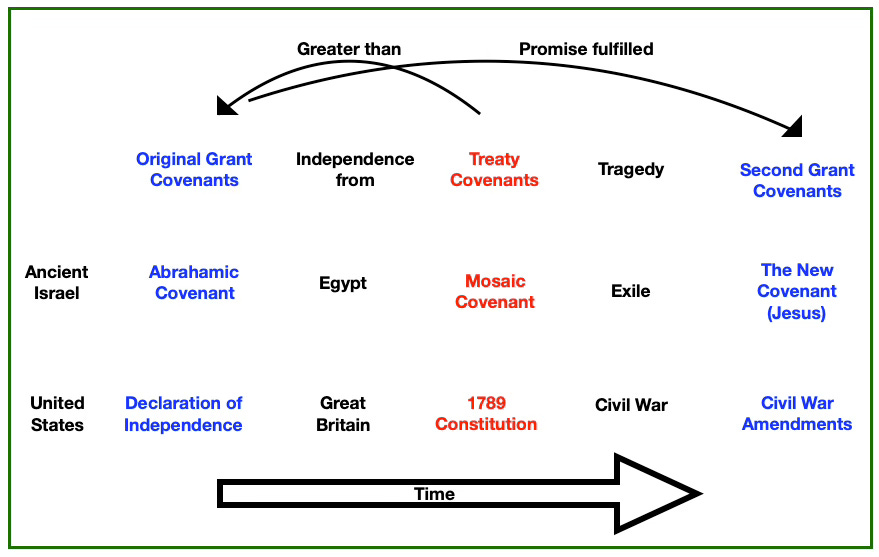

America’s story can be told through three national covenants—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Constitution’s Civil War Amendments. This national story bears a striking resemblance to the New Testament’s story of Israel told through three of its national covenants.

In fact, by studying how the New Testament writers interrelate these three covenants and by renewing its own covenants accordingly, America can readopt its broad constitutional values that it forsook after Reconstruction.

Two sets of three interrelated covenants

The New Testament speaks of the relations among three covenants—God’s covenants with Abraham, Moses, and Jesus—to encourage its readers’ participation in God’s covenant with Jesus (what it calls the “new covenant”). Lincoln does something like that, too, speaking of America’s first two covenants to encourage allegiance to the coming covenant, to the “new birth of freedom” he speaks about at Gettysburg. After the Civil War, this “new birth of freedom” would take the form of the Constitution’s Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments (the “Civil War Amendments”).

I don’t know if Lincoln was aware that he was taking the New Testament’s slant on three similar covenants. But he sure was taking it.

I’ll walk us through more details about these six covenants—two parallel sets of three covenants—to demonstrate that the call to covenant renewal in the New Testament books of Galatians and Hebrews can help guide America to covenant renewal, too. (During this “walk,” you may wish to use the handy table below.)

The two countries’ grant and treaty covenants

The ancient Near East practiced two kinds of covenants, and in the Bible, God enters into both kinds. The first kind, Rabbi Everett Fox says, is a “freewill granting of privileges,” and the second kind is “an agreement of mutual obligations between parties.”1 Hebrew examples of a “freewill granting” covenant include God’s covenants with Noah, Abraham, and David. The Bible’s chief example of a “mutual obligations” covenant, of course, is the Mosaic covenant, the covenant that includes the Ten Commandments (and 603 other commandments).

Rabbi Moshe Weinfeld makes the same distinction as Fox does between two ancient Near East covenant types, but Fox’s “freewill” covenants become Weinfeld’s “grant” covenants, and Fox’s “obligations” covenants become Weinfeld’s “treaty” covenants. The distinctions between grant and treaty covenants are stark, Weinfeld says:

While the “treaty” constitutes an obligation of the vassal to his master, the suzerain, the “grant” constitutes an obligation of the master to his servant. In the “grant” the curse is directed towards the one who will violate the rights of the king’s vassal, while in the treaty the curse is directed towards the vassal who will violate the rights of his king.2

In other words, the grant covenant puts the grantee in a new, greater, and protected political space, while the treaty covenant contains rights the grantee may exercise and obligations the grantee must meet.

Israel started with a grant covenant. God granted Abraham, the first Hebrew, the land that he could see in all four directions,3 and telling him that “I will make you a great nation.”4

Similarly, the United States began with a grant covenant. The Declaration of Independence in 1776 was not instituted by God, though, but “by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies,” and it extended to those same people a new nation on the land on which they found themselves.

These two first grant covenants are similar. God’s covenant to Abraham is short and focuses on a universal promise: “In your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed.”4 Similarly, the Declaration of Independence is short and focuses on a universal truth: “All men are created equal.”

After receiving their founding grant covenants, both nations obtained freedom from nations that had ruled them, Israel from Egypt and the United States from Great Britain (1783). Following their independence, each nation struggled with governing itself, and those struggles led to each nation entering into its treaty covenant.

These treaty covenants set out how the newly independent nations would function. Treaty covenants are “the obligatory type reflected in the Covenant of God with Israel,” Weinfeld says,5 and they describe the citizens’ responsibilities to the government and to one another. The Mosaic covenant Weinfeld mentions finds its analog in the United States Constitution.

Like the two founding grant covenants, the two treaty covenants are similar. Both the Mosaic covenant and the U.S. Constitution are long; both set out specific rights, duties, and governmental structures; and both have spawned lots of written commentary. The Mosaic covenant’s commentary is in the form of the lengthy Talmud and Midrash construing its provisions, and the United States Constitution’s commentary is in the form of voluminous court opinions, treatises, and law review articles construing its provisions.

While operating under their treaty covenants, both nations took land from other peoples,6 and both nations enslaved other peoples.7 Both nations broke provisions of their treaty covenants. The Israelites’ offenses against the Mosaic covenant led to Israel’s exile. The Confederate states’ withdrawal from the Constitution led to America’s Civil War.

At the end of these catastrophes, each nation entered into a second grant covenant. According to the New Testament, the new covenant through Jesus’s death on the cross in some sense ended Israel’s exile.8 In the United States, the Union’s victory in the Civil War led to ratification of the three Civil War Amendments.9

To summarize the parallels discovered so far, the three greatest covenants referred to in the New Testament follow a certain pattern: the Abrahamic Covenant is the founding “grant” covenant (granting and protecting the rights of its grantees), the Mosaic covenant (“the law”) is a “treaty” covenant (setting out the obligations of those covenanting), and the new covenant is a second “grant” covenant.10

The three greatest United States covenants follow the same pattern: the Declaration of Independence is the founding grant covenant, the Constitution is a treaty covenant, and the Civil War Amendments, taken together, amount to a second grant covenant.

The grant covenants’ superiority over the treaty covenants

Here’s how the covenants work together in each nation. The Bible’s new covenant reaches back to the first grant covenant (the Abrahamic covenant) to finally fulfill the earlier grant covenant’s universal language (“all the nations of the earth shall be blessed”). The new covenant does so by including the world’s other nations into Abraham’s covenant.11 Likewise, the Civil War Amendments reach back to the first grant covenant (the Declaration of Independence) to fulfill the earlier grant covenant’s universal language (“all men are created equal”) by including African Americans into the covenant.

Each country’s two grant covenants and its treaty covenant interrelate the same way, too. Lincoln and the writer of Hebrews have the same message: the second grant covenant is superior to the treaty covenant because the first grant covenant is superior to the treaty covenant. And the first grant covenant is superior to the treaty covenant even though the latter comes after the former.

The Writer of Hebrews, for instance, in order to show the preeminence of the new covenant, takes pains to establish that the Abrahamic covenant is greater than the Mosaic covenant. One way he does this is by examining who tithes to whom. The lesser tithes to the grater, he points out, and Levi under the Mosaic covenant collects tithes from the other tribes. But Levi, even though he has the honor of receiving tithes, in essence pays tithes to Melchizedek, the priest of the Abrahamic covenant, through Abraham because Abraham is Levi’s ancestor. Therefore, since the Mosaic covenant tithes to the Abrahamic covenant, the Abrahamic covenant is greater than the Mosaic covenant.12

Hebrews’s point with regard to the relations between the first two covenants is that, because the founding grant covenant points to the second grant covenant and is superior to the later treaty covenant, the second grant covenant takes precedence over the treaty covenant, too, and modifies it significantly.

Lincoln makes a similar argument to the one in the book of Hebrews, demonstrating the Declaration of Independence’s superiority to the Constitution even while defending the Constitution against both abolitionists and secessionists. When Garrisonian abolitionists attack the treaty covenant (the Constitution) as pro-slavery, Lincoln defends it by saying that the treaty covenant serves and defends the original grant covenant (the Declaration of Independence). Lincoln compares the Declaration to an apple that is protected and set off by the Constitution, the apple’s picture frame:

The assertion of that principle [liberty for all], at that time, was the word, “fitly spoken” which has proved an “apple of gold” to us. The Union, and the Constitution, are the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it. The picture was made, not to conceal, or destroy the apple; but to adorn, and preserve it. The picture was made for the apple—not the apple for the picture.13

In this passage, using Proverbs 25:11 as his metaphorical framework, Lincoln says that the apple—the Equality Clause in the Declaration of Independence—is greater than the picture frame that adorns and protects it—the Constitution. The picture (the Constitution) was made for the apple (the Declaration) in order to protect it. Lincoln defends the Constitution against the abolitionists’ attack because the Constitution defends the Declaration and its Equality Clause.

Lincoln’s message to the Southern secessionists is similar. When they argue that the Constitution’s provisions permit the expansion of slavery into the United States’s western territories, Lincoln argues that the Constitution has to be read with the Declaration of Independence’s Equality Clause in mind. Political theorist Harry V. Jaffa says as much:

. . . the meaning of the Constitution in respect to its protection of private rights depended upon the understanding of the Declaration of Independence and its application to the Constitution.14

Because the Declaration’s Equality Clause asserts that all men are created equal, the inconclusive Constitution is construed against extending slavery into the territories.

Even while addressing the polar-opposite constitutional positions of the abolitionists and secessionists, then, Lincoln makes the country’s treaty covenant subservient to the country’s founding grant covenant.15

The second grant covenants as fulfillments of the first ones

Both nations’ founding grant covenants were designed to include more peoples than the treaty covenants allowed for, and that inclusion makes way for the second grant covenants. Paul argues in his letter to the Romans that God’s covenant to Abraham makes Abraham “the father of us all”—gentile nations included.16 As Miroslav Volf points out, Paul even amends a single word in Genesis’s account of God’s covenant with Abraham, substituting God’s promise that Abraham will inherit the land with God’s promise that Abraham will inherit the world.17 Paul’s amendment suggests that the first grant covenant’s promised land has grown into the second grant covenant’s entire world.

Similarly, Lincoln extends the reach of the first grant covenant by arguing that the nation’s Founding Fathers are also the fathers of those who didn’t descend from them by blood and whose ancestors weren’t in America by 1776—“German, Irish, French and Scandinavian” people, for instance, who immigrated to America after Independence—thanks to the founding covenant’s Equality Clause:

If they [the immigrants] look back through this history to trace their connection with those days [of the American Revolution] by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us, but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel the moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are. This is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.18

Lincoln emphasizes here the worldwide calling of the Declaration’s Equality Clause. During the Civil War, too, in his Gettysburg Address, Lincoln asserts the importance to the world of a government dedicated to the Equality Clause. In this brief address, Lincoln twice gives the Equality Clause and our nation dedicated to it an international reach, referring to “any nation so conceived and so dedicated” to the clause and urging that government of, by, and for the people “shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln, then, gives America’s grant covenants the same worldwide reach that Paul gives to what he understands as being Israel’s grant covenants.

And of course, America’s second grant covenant (the Civil War Amendments) fulfills the promise of the first grant covenant (“all men are created equal”) by ending slavery and extending due process and equal protection to Blacks.

Both Paul and Lincoln, the greatest advocates of their respective nations’ second grant covenants,19 therefore view our relationship to the Bible’s and America’s founding grant covenants mystically and not literally20 in order to include people of all races and nations into those earlier covenants.

Plug and play: Lincoln fits into Paul’s covenant talk

Lincoln’s message about the way the three greatest American covenants interrelate is the same as Paul’s message to the Galatians about how God’s three main covenants interrelate. In fact, by (1) highlighting Paul’s concepts in a passage from Galatians 3 about how the three covenants interrelate, (2) substituting Lincoln’s concepts for Paul’s, and (3) comparing the original and reworked passages, we discover that the two authors understand the interrelationships among their respective trinity of covenants the same way.

Here’s Galatians 3:17 - 19, 21, 23 - 24 from the Revised English Bible, with Paul’s concepts in bold:

What I am saying is this: the Law, which came four hundred and thirty years later, does not invalidate a covenant previously ratified by God, so as to nullify the promise. For if the inheritance is based on law, it is no longer based on a promise; but God has granted it to Abraham by means of a promise. Why the Law then? It was added because of transgressions, having been ordained through angels by the agency of a mediator, until the seed would come to whom the promise had been made. . . . Is the Law then contrary to the promises of God? May it never be! For if a law had been given which was able to impart life, then righteousness would indeed have been based on law. . . . But before faith came, we were kept in custody under the law, being shut up to the faith which was later to be revealed. Therefore the Law has become our tutor to lead us to Christ . . .

Here’s the same passage, now with Lincoln’s concepts substituted for Paul’s:

What I am saying is this: the 1789 Constitution, which came thirteen years later, does not invalidate the Declaration of Independence previously ratified by the Founding Fathers, so as to nullify the promise of equality. For if our political inheritance is based on the 1789 Constitution, it is no longer based on a promise; but God has granted it to Americans by means of a promise. Why the 1789 Constitution then? It was added because of transgressions—slavery—having been ordained through “We the People” by the agency of a convention and ratification process, until the seed would come to whom the promise had been made—African Americans. . . . Is the 1789 Constitution then contrary to the promises of the Declaration of Independence? May it never be! For if a constitution had been given which was able to impart rights, then our rights would indeed have been based on the Constitution. . . . But before the Civil War came, we were kept in custody under the 1789 Constitution, being shut up to the equality which was later to be revealed. Therefore the 1789 Constitution has become our tutor to lead us to the Constitution’s Civil War Amendments . . .

This summary of Lincoln’s covenantal understanding is expressed more fully in his July 4, 1861 message to Congress, and it’s expressed even more succinctly and poetically in his Gettysburg Address.

The neglected power of America’s second grant covenant

Political philosopher and historian Garry Wills argues that the Gettysburg Address “remade America.”21 The address’s first line, claiming that America was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” reoriented America from a pro-slavery, strict construction of its treaty covenant, the Constitution, to what Lincoln argues was the founders’ original intent: making the treaty covenant serve the original grant covenant. By doing so, the Gettysburg Address prepared America for its ultimate grant covenant, the Constitution’s Civil War Amendments.

The Gettysburg Address encourages devotion to America’s grant covenants, both to the Declaration of Independence and the “new birth of freedom”—the Civil War Amendments—that Lincoln then foresaw. Lincoln’s short speech uses the word “dedicate” in various tenses six times, and it uses synonyms of “dedicate”—“consecrate,” “hallow,” and “devotion”—an additional five times. We read the Gettysburg Address with something like piety, but like the original recipients of the New Testament’s letters to the Hebrews and Galatians, we Americans have largely lost our devotion to our second grant covenant if we even acknowledge the covenant’s existence at all.

The Civil War Amendments didn’t come to destroy the Constitution but to fulfill its promise in the Declaration of Independence. Historian Eric Foner, who calls the three Civil War Amendments America’s “second founding,” quotes former Union General Carl Schurz’s characterization of the amendments as a “constitutional revolution” that “found the rights of the individual at the mercy of the states . . . and placed them under the shield of national protection. It made the liberty and rights of every citizen in every state a matter of national concern.”22

Foner’s summary of the amendments’ contents, however, seems to belie their expansive character:

The Thirteenth [Amendment] irrevocably abolished slavery. The Fourteenth constitutionalized the principles of birthright citizenship and equality before the law and sought to settle key issues arising from the war, such as the future political role of Confederate leaders and the fate of Confederate debt. The Fifteenth aimed to secure black male suffrage throughout the reunited nation.23

The Civil War Amendments’ expansive character comes from some of their deliberately broad wording—“citizen,” “privileges or immunities,” “equal protection,” “due process”—as well as the amendments’ invitations to Congress to enforce the amendments through “appropriate legislation.” As Foner says, “Congress built future interpretation and implementation into the amendments.”24 These enforcement clauses were to guarantee “that Reconstruction would be an ongoing process, not a single moment in time.”25

But the Amendments’ invitations to the Supreme Court and to future Congresses to act as a community of interpretation have been largely ignored, contributing to the premature end of Reconstruction, the re-subjugation of Blacks, the passage of Jim Crow laws, and the nation’s blind eye to the frequent spectacle of lynchings. Even before the end of Reconstruction, Congress and the Supreme Court began to retreat to the pre-Civil War Constitution,26 much as the original recipients of the New Testament’s letters to the Hebrews and Galatians had retreated to the Mosaic covenant.

The Civil War Amendments still don’t do fully what they were ratified to do.

The Thirteenth Amendment’s “latent power has almost never been invoked as a weapon against the racism that forms so powerful a legacy of American slavery,”Foner points out.27

The Fourteenth Amendment has been hobbled by the state action doctrine, which narrows the amendment’s reach. This doctrine has been used, Foner says,

in rulings that do not allow race to be taken into account in voluntary school desegregation programs, on the grounds that segregation today results not from laws, as in the past, but from “private choices” that produced racially homogeneous housing patterns. This sharp distinction between public and private action makes it difficult to address the numerous connections between federal, state, and local housing, zoning, transportation, and mortgage insurance policies, and the “private” decisions of banks, real estate companies, and individual home buyers, that together have produced widespread segregation in housing and education.28

Like the Thirteenth Amendment, which has been interpreted narrowly, the Fifteenth Amendment is mostly irrelevant today, Foner says:

It did provide constitutional sanction for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which restored the suffrage to millions of black southerners, as well as the more modest voting provisions of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1964. To this day, however, the right to vote remains the subject of bitter disputation. Many states have recently enacted laws that do not explicitly mention race or ethnicity but impose suffrage requirements that seem designed to restrict the voting rights of blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans. The Supreme Court has upheld some of these laws; others remain the subject of litigation.29

In general, the courts have ignored the force of the second founding by substituting “racial classifications” for inequality “as the root of the country’s race problems”:

This outlook, rooted more in modern-day politics than the actual history of the Reconstruction era, has helped to fuel a long retreat from race-conscious efforts to promote equality.30

This overall failure to understand the Civil War Amendments as a second founding was not only a reaction to the Union’s Civil War-era values but also a failure of covenantal hermeneutics. Covenants are ongoing and must be tended by covenant communities; consequently, as Foner says, “the creation of meaning is an ongoing process. Freezing the amendments at the moment of their ratification misses this dynamic quality.”31 As Thaddeus Stevens said during the Civil War Amendments’ ratification process, “We are not now merely expounding a government. We are making a nation.”32 But subsequent Congresses and Supreme Court cases generally have treated the Civil War Amendments as something far less than a second founding.

The neglected distinction between original intent and strict construction

Both before and after the Civil War Amendments, the Supreme Court has tended to interpret the treaty covenant’s provisions either through the lens of “the living constitution,” which has little use for the covenant’s actual language, or through the lens of strict construction, which interprets the treaty covenant’s provisions without regard to the guidance provided by either the earlier or later grant covenants.

But questions of covenantal hermeneutics ultimately don’t resolve strictly in a covenant’s provisions, as important as those provisions are. Conflicting covenantal provisions resolve in a people, in a community of interpretation that never ceases to testify and to interpret others’ testimony. That’s what the Declaration of Independence and the Civil War Amendments allow people and courts to do.

There’s a distinction between original intent and strict constructionism. The sources are different, as Jaffa points out: “In asking what were the original intentions of the Founding Fathers, we are asking what principles or moral and political philosophy guided them. We are not asking their personal judgments on contingent matters.”33 The original intentions of the Founding Fathers—the “principles or moral and political philosophy” that guided them—are contained in the earlier grant covenant, the Declaration of Independence.

John Hancock and John Marshall agreed that a proper reading of the Constitution would be mediated by the Declaration’s principles. When Hancock, the president of the Second Continental Congress, sent the Declaration of Independence to the states, he included a cover letter calling the Declaration the “Ground & Foundation of a future Government.”34 Marshall’s Supreme Court interpreted the Constitution this way for the first thirty-five years of the nineteenth century, citing natural law principles summarized in the Declaration many times in mostly unanimous opinions.35

The problem with strict constructionism, then and now, is that the approach doesn’t distinguish between the Constitution’s truths and its compromises. There’s an even worse aspect of strict construction’s legalistic and literal approach: it denies that there are truths that give the Constitution its moral authority. In other words, it denies natural law. This denial is evident in the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s summary of his own strict constructionist hermeneutic:

If [a democratic] society adopts a constitution and incorporates in that constitution safeguards for individual liberty, these safeguards do indeed take on a generalized moral rightness or goodness. They assume a general social acceptance neither because of any intrinsic worth nor because of any unique origins in someone’s idea of natural justice, but instead simply because they have been incorporated in a constitution by the people.36

Rehnquist here claims that a truth is true because it’s in the Constitution—and for no other reason. Lincoln, Jefferson, Madison, and the rest of the Founders would say, however, that the Constitution is true to the extent that it’s consistent with natural law, and it’s needful to the extent that it protects natural law.

Think of the ramifications of the strict constructionist view that “moral rightness or goodness” attaches to a constitutional passage by virtue of its inclusion in the Constitution. Jaffa has pointed out that Justice Rehnquist “doesn’t believe that we can say that despotism is intrinsically evil.” Professor Bruce Ledewitz shows how Rehnquist “is unable to affirm any substantive value as true or good.”37

Whatever the Constitution says, goes, the strict constructionists say. We don’t employ any morality in reading it, even the self-evident truths mentioned in the Declaration and in eight of the original thirteen states’ constitutions. Strict contstructionism’s moral relativism amounts to nihilism as Edward Erler has defined it: “Nihilism is the belief that the metaphysical freedom of man is merely a delusion.”38 Strict construction’s version of nihilism avers that if it’s not explicitly stated in the Constitution, it’s a delusion.

Jesus battles the strict construction of Israel’s treaty covenant several times. On one occasion, he is confronted by the scribes and Pharisees who have brought an adulterous woman with them:

“Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of adultery. In the law Moses has laid down that such women are to be stoned. What do you say about it?”39

In suggesting that the sinless among them cast the first stone, Jesus offers a hermeneutic that interprets the Mosaic covenant by the values that animate it, which he summarizes elsewhere as “justice, mercy, and good faith.”40 In other words, Jesus substitutes God’s original intent for the scribes and Pharisee’s strict construction.

America’s and ancient Israel’s constitutional hermeneutics, then, like their journeys through their respective covenants, bear more than a striking resemblance to each other. These journeys establish a pattern of covenanting that goes beyond the merely national concerns of treaty documents. The founding grant covenants—the Abrahamic covenant and the Declaration of Independence—remind us that our most sacred covenants are animated by the even more sacred character of God, that our peoples’ callings extend to all races and nations, and that we practice political freedom not just for ourselves but for the benefit of the world.

The footnotes refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Fox, Five Books of Moses, 360.

Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant,” 185.

Genesis 13:14-17.

Genesis 12:2 NNAS.

Weinfeld, 184-85.

See gen. the book of Joshua.

Numbers 31:17-18; Deuteronomy 21:1-14.

Wright, Day the Revolution Began, 107-19.

Parallels could also be made between the American and biblical covenants that preceded the initial grant covenants. The Noahic Covenant and the Mayflower Compact were each made at the end of a long sea voyage that left an old, offending world behind. Both of these covenants focused on the human need for survival. God’s covenant with Noah focuses on “never again”: “I establish My covenant with you; and all flesh shall never again be cut off by the water of the flood, neither shall there again be a flood to destroy the earth.” Genesis 9:11 NNAS. Likewise, the Mayflower Compact may have been entered into because the parties to it feared for their lives, according to Hannah Arendt: “. . . they obviously feared the so-called state of nature, the untrod wilderness, unlimited by any boundary, as well as the unlimited initiative of men bound by no law.” Arendt, On Revolution, 158.

Weinfeld, 185.

During Pentecost, Peter quotes God’s words to Abraham and says that they are now being fulfilled. Acts 3:25-26.

Hebrews 7:1-19.

Lincoln, “Fragment on the Constitution.”

Jaffa, New Birth of Freedom, 276-77.

As Jaffa puts it, Lincoln and his party insisted “upon a distinction between the Constitution’s compromises and its principles,” and its principles were anchored in the Declaration of Independence. Jaffa, 90. In 1825, both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison seemed to presage Lincoln’s position. As members of the University of Virginia’s board of visitors, they wrote the board that the university’s law students should consider the Declaration of Independence as the best guide to the principles of the United States Constitution. Jaffa, “Original Intentions,” 363.

Romans 4:16 KJV.

Romans 4:13; Volf, Exclusion and Embrace, 42.

Abraham Lincoln, July 10, 1858 speech at Chicago, Illinois, Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 1832-1858, 455-56. Jaffa said that for Lincoln, “the moral and political teaching of the Gospels had an apocalyptic fulfillment in the American Founding.” Jaffa, 352.

Although Lincoln died before the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were drafted and ratified, he worked hard to have Congress send the Thirteenth Amendment, which would abolish slavery, to the states for ratification. Morel, “Forced into Gory,” 205.

Alexander H. Stephens, Lincoln’s friend and the Vice-President of the Confederacy, said that “with Lincoln the Union rose to the sublimity of mysticism.” The literary critic Edmund Wilson quotes Stephens and agrees with him. Wilson, Eight Essays, 197.

Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg. The book’s subtitle suggests Wills’s argument: “The Words that Remade America.”

Foner, Second Founding, xxviii.

Foner, xix.

Foner, xxv.

Foner, xx.

Foner, xxvi.

Foner, 170.

Foner, 173.

Foner, 170.

Foner, 174.

Foner, xxiv-xxv.

Foner, 97.

Quoted in Erler, “Introduction,” xxxiv.

Quoted in Erler, “Introduction,” xxxiv.

Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer of a Nation, Owl Books ed, A Marian Wood / Owl Book (New York, NY: Holt, 1998), 282-524.

Harry V. Jaffa, “The False Prophets of American Conservatism,” Claremont Review of Books, September 29, 1998, https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/the-false-prophets-of-american-conservatism/.

Jaffa, “What Were the ‘Original Intentions,’” 423-24.

Erler, xl.

John 8:1-11 REB.

Matthew 23:23 REB.

My goodness: thorough, thoughtful, compelling. Thanks, Bryce!