Your conception of God might affect your politics

A theologian's test could help us reclaim our political lives

There is hardly any human action, however particular a character be assigned to it, which does not originate in some very general idea men have conceived of the Deity, of his relation to mankind, of the nature of their own souls, and of their duties to their fellow-creatures. Nor can anything prevent these ideas from being the common spring from which everything else emanates.

— Alexis de Tocqueville1

Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father.

— Jesus2

If your faith permits it, reflect on your conception of God.

This simple exercise gets at a core reality at the intersection of religion and politics. The exercise is also reductive, I admit, like a personality test. Insight comes at the expense of complexity. But I'll add—or at least outline—some complexity shortly.

The scary part of this exercise may be something I didn't ask you to do: how do all those misguided people supporting the other candidate conceive of God?

But this isn't red-versus-blue stuff. It's participation-versus-authoritarian stuff.

I credit Protestant theologian Marcus J. Borg with the inspiration for this exercise. Borg wrote a book, called The God We Never Knew, about how our conception of God affects our outlook on many things, including politics.3 Borg's book, by the way, like this exercise, is targeted to Western Christians, so if you're not one—or if your political thinking hasn't been much affected by a Western Christian heritage—I can't stand behind the results.

With those claims, credits, and caveats in mind, let's look at one typical conception of God held by many Western Christians.

Something like an old, stern white dude with a long, white beard.

If that’s part of your portfolio of God-conceptions, you're not alone. But you knew you had company: your mind's eye might have seen the same conception in many of your fellow citizens' minds.

Borg started his church life with the same conception. He grew up Lutheran, and when as a kid he thought of God, he pictured his stern, lecturing gray-haired pastor:

When I prayed, I visualized Pastor Thorson’s face. I knew, of course, that he wasn’t God; even as a preschooler, I would have said, “No,” if someone had asked me if he were. But when I thought about God or prayed to God, I “saw” Pastor Thorson.4

This respected theologian "saw" God as Thorson for thirty years. Borg’s childhood image of God, which persisted for years after his theological training,5 suggests the power culture can have over what we know of whom the New Testament proclaims as the “invisible” God.6

For a simplistic summary of Borg and the ramifications of Thorson-as-God, we turn to a former Harvard professor, David Korten, who apparently didn't read Borg's book. However, in his own book, Korten tells how he once shared a podium with Borg. Korten summarizes how Borg that night connected our image of God with our politics:

Borg explained that the image of God as a distant patriarch translates into a hierarchy of righteousness and supports a politics of authority, domination, and competition for power. The image of God as a universal spirit manifest in all creation supports a politics of cooperation, compassion, and sharing.7

Korten comes away from Borg's talk with a pretty binary take on Borg and politics. Korten's take suggests that monarchists and authoritarians tend to see God as a distant patriarch, and republicans (small "r") and democrats (small "d") tend to see God as the universal spirit.

Where does that leave our default politics? It's easy to anthropomorphize. It's easier to "see" an old, "distant patriarch" than it is to "see" a spirit. I mean, even our ghosts are anthropomorphic. So if it comes down to how we “picture” God, the monarchists and authoritarians have it easy. The republicans and democrats and many anarchists—those who love civic engagement—will always struggle.

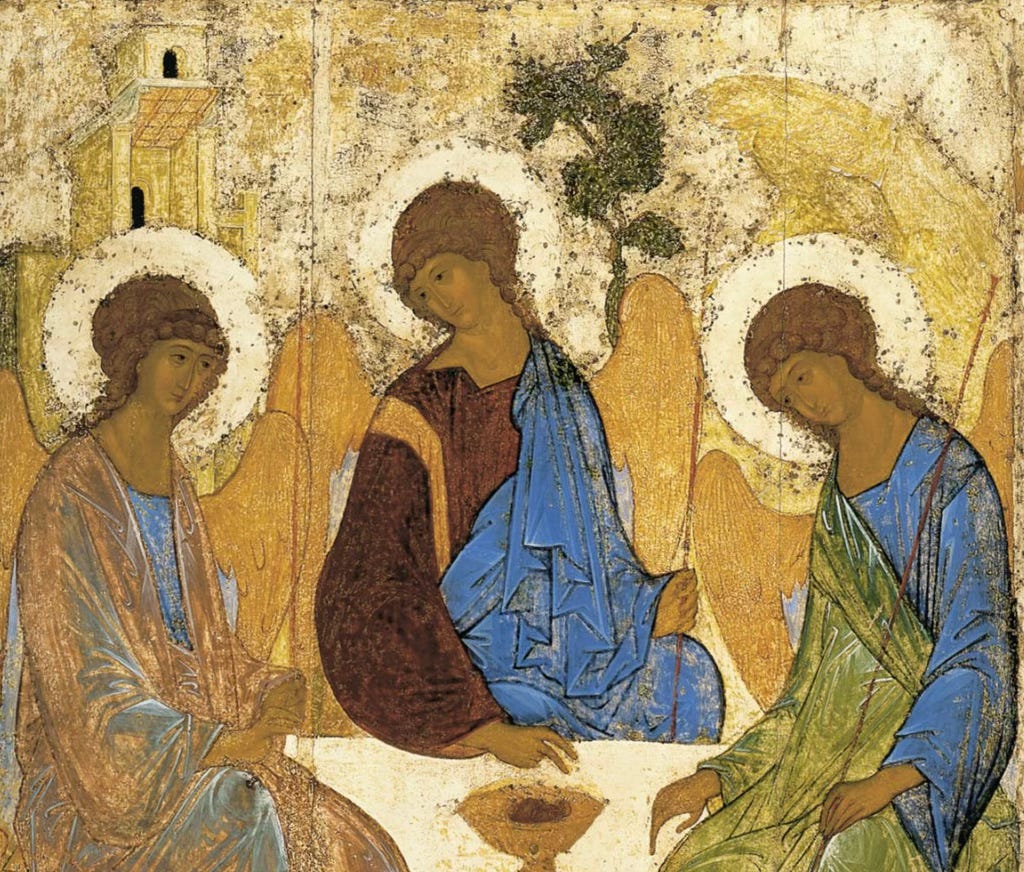

Above: The Trinity (also called The Hospitality of Abraham) by Andrei Rublev (detail)

The modern struggle against authoritarians as God's representatives

Others have struggled long and hard against the same human tendency to associate God with patriarchs and patriarchs with politics. I'll give three examples of this struggle.

The first example is feminism. Feminists of all genders, of course, find the God-as-patriarch model particularly damaging. Patriarchalism affects politics, but it also undermines people's humanity. Borg points out that patriarchalism makes women out as less than the image of God and as, therefore, less than human.8 One well-regarded feminist response to the model has been to posit God as female. Many of these feminists (and others) have found such a God in the Bible. God's name El Shaddai is used there 58 times, and the name can be translated as "the god with breasts."9

The second example is republicanism. The Florentine republic of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was threatened by monarchy within and without. The monarchists had an advantage: people tend to assume that monarchs operate under God's authority, as J.G.A. Pocock points out:

As the roaring of a lion, the king spoke with authority that descended to him from God; his authority therefore became inscrutable, mysterious, and not to be resisted.10

J.G.A. Pocock's book The Machiavellian Moment is in part the story of how Florence and subsequent states slowly overcame this monarchial advantage and arrived at governments under law based on a balance of powers.11

The third and final example is liberalism—specifically, John Locke's liberalism. You've heard of Locke's Second Treatise on Civil Government? The treatise that the American founders relied on in part to justify a revolution against an unjust king and the Parliament he represented? Few, though, talk about Locke’s First Treatise. It's a little dull unless you like biblical arguments against patriarchalism, which by the seventeenth century was a well-developed school of political philosophy. Locke has to clear away patriarchalism to make room for his Second Treatise's argument in favor of a constitutional monarchy and in favor of other forms of government under law.

The divine right of kings is a modern concept

Patriarchalism in Locke's day made an explicit connection between a nation's king and an individual family's dad—that is, a dad who alone governed his household and governed it as he pleased.12 Patriarchalists such as Robert Filmer, the First Treatise's main antagonist, traced kings' lineages back to Adam, who was made in God's image.13 Filmer found a more receptive audience than Locke in England’s King James, who believed in patriarchalism and tried to become England's first absolute monarch.

At this point, many people get confused. We tend to think that "the divine right of kings," the doctrine that gave God's imprimatur for absolute monarchs, dates back to the Middle Ages. But as philosopher Alexander S. Rosenthal points out, absolute monarchy and "the divine right of kings" are modern concepts:

Contrary to a popular misconception, the absolutist conception of government where the sovereign or king is both the source of law and above the law is much more a product of early modern thinkers (e.g., Bodin) than the medieval tradition. The medieval political order rested on a delicate balance between kings, feudal princes, and the Roman Catholic church, with the whole structure conceptualized as a loose unity under the Pope as spiritual head and the Emperor as temporal head.14

In other words, European kings became more absolute, not less, after the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages, European kings in general were under law, and their power was balanced with the powers of other groups within the polity. (The nobles forcing King John to sign Magna Carta, for instance, weren’t taking modernity’s first step towards freedom. They were enforcing the Middle Ages’s general prohibition against sovereignty.)15

How did the nature of kingship change in the early modern era? Some intellectual historians and political theorists link the change in the Western conception of kings to a big change in the Western conception of God.

In the Middle Ages, kings were under law, like the Trinitarian God

During the Middle Ages, Europeans generally understood God as the Trinity. Consequently, their government structures were also generally trinitarian.

The New Testament understanding of the proto-Trinity involves a covenant between God the Father and God the Son witnessed by the Spirit and fulfilled at Jesus's resurrection.16 We enter that covenant through the Son as children of God, and we receive the Spirit as the tangible promise of our own resurrection on earth.17

For this covenant to happen, God must be willing and able to bind himself. God's penchant in both the Hebrew Bible and in the New Testament to bind himself is the foundation of limited government in the West, according to Professor of Social and Political Ethics Jean Bethke Elshtain:

For if the sovereign God is omnipotent and if his will prevails, it follows that God's sovereignty would be a terrible tyranny were God not bound. No humans can bind God; perforce, he binds himself. A number of scholars see the beginnings of constitutionalism in the claim that even as God binds himself freely, so the king or ruler must be freely bound.18

Like God, like king. And where God is participatory, defined by the relationships among his persons, the polity is, too. When it lived up to its ideals (and it often didn't), the politics of the Middle Ages involved a balance of many powers, according to Professor of Theological Ethics Luke Bretherton. He describes

. . . the complex and overlapping jurisdictions of medieval Christendom in which the sovereign authorities of the pope, emperor, kings, abbots, bishops, dukes, doges, mayors, and various forms of self-governing corporations were interwoven with each other . . .

What might seem like chaos to the modern, state-centered conception of government was instead dynamic and participatory:

This kingdom, seeming divided against itself, could be encompassed within an overarching vision of the providential ordering of the whole wherein each authority participated in and contributed to the governance of the single economy of God's kingdom.19

When God became lawless, so did kings

But when God changed, kings changed. In the early modern era, Europeans began to understand God as pure will in a world without universals. Europe began to move away from a covenant-making God and slowly aligned itself with theologians Duns Scotus and William of Ockham. Bretherton sets out the position of several theologians with regard to the effects of voluntarism and nominalism:

The theologians John Duns Scotus (c. 1265 - 1308) and William of Ockham (c. 1288 - 1348) are identified as central to the shift from a participatory metaphysics to one in which God's sovereign will is the ultimate principle of being (voluntarism) and the adoption of the view that universals do not refer to real things but are merely mental concepts (nominalism). The shift to voluntarism and nominalism is a shift from seeing God as Logos (that is, as loving, relational and Trinitarian divine presence in whose created order humans can participate creatively through reason) to seeing God as a sovereign (a universal being whose omnipotent will is unbounded, absolute, infinite, and indivisible).20

Professor Peter Kreeft examines what Ockham’s God of pure will is like:

In Ockham's theology, God Himself is totally irrational: There are no universal rules for the divine mind. God is pure will, and totally free beyond the universal bounds even of logic. Ockham says that God, being omnipotent, could do anything. He could make a square circle. He could make a man a donkey—not just make a man turn into a donkey, but make a man to be a donkey even though he is a man. He says that God could cause the sense experience of a star to exist in us when the star does not exist. . . . So we can't know any universal laws at all.21

Would an earthly king be much different than such a God? In a 1609 address to Parliament, King James, whose patriarchalism was influenced by voluntarism and nominalism, suggested that the answer is no. James wasn’t particularly demure about it, either:

For if you wil [sic] consider the Attributes to God, you shall see how they agree in the person of a King. God hath power to create, to destroy, make, or unmake at his pleasure, to give life, to send death, to judge all, and to be judged nor accompatible [sic] to none. To raise low things, and to make high things low at his pleasure, and to God are both sould [sic] and body due. And the like power have Kings: they make and unmake their subjects: they have power of raising, and casting downe: of life, and of death: Judges over all their subjects, and in all causes, and yet accompatable to none but God onely. They have power to exalt low things, and abase high things, and make of their subjects like men at the Cheese.22

King James compares kings abasing their subjects to men slicing cheese. More importantly for our purposes, James compares God’s power to destroy “at his pleasure” to a king’s power “of life, and of death.”

A God of "pure will" who can ignore his covenants leads to an absolute monarch who can ignore the law.

Jesus is both "the image of God" and the Other

The New Testament is clear about how we can, in a sense, picture God. Paul refers to Jesus as "the image of the invisible God."23 We can’t quite picture Jesus, though we know he wasn’t old or white. Instead, we encounter Jesus in others. Jesus taught us to see him in "the least of these brothers or sisters of Mine."24

Jesus, then, can be understood as the Other. John O'Donohue called Jesus "the first Other in the universe . . . the prism of all difference."25 A simple syllogism based on Jesus as God's image and Jesus as the Other leads us to see God as the Other, even as the stranger or as the alien. What an impact this image of God would have on our politics.

God's kingship is subversive of human kingdoms

Jesus, of course, in covenant with his Father, also accepted the title of Lord and Messiah, or king. This understanding of Jesus as both king and Other—the stranger and the alien—suggests the subversive nature of God's Kingdom. Borg puts it this way:

Rather than being the legitimator of domination systems, God as king and lord is the subverter of systems of domination. God is lord, not pharaoh; God is king, not the king in Jerusalem; Jesus is king, not the Herods or Caesars of this world; God is lord, not the superego. God as king is the compassionate warrior who grieves with and takes the side of those who suffer under domination systems.26

By contrast, rather than being subversive of human sovereignty, the modern, monistic image of God is static. In semiotic terms, it is dyadic, involving only a sign (an old guy with a white beard, say, or a woman) and what the sign signifies (God). With this model, authoritarians find it easy to become an earthly sign for an otherworldly God.

But the trinitarian God is dynamic. In semiotic terms, God is triadic, involving a sign (Jesus), what the sign signifies (Being, or God the Father), and an interpretant (the Spirit). We can’t picture Jesus, exactly, but by the Spirit we encounter the Other as Jesus. In doing so, we are brought into “the kingdom of [God’s] dear Son.”27

More than any mental image of God, these encounters with the Other change our politics. We participate. We work for justice. We discover ourselves and others in God's public world.

The short footnotes below refer to the full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 390.

John 14:9 REB.

Borg, Marcus J. The God We Never Knew: Beyond Dogmatic Religion to a More Authentic Contemporary Faith. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997.

Borg, 15-16.

Borg, 29.

Colossians 1:15; 1 Timothy 1:17.

Korten, Change the Story, 14.

Borg, 70.

Biale, David. “The God with Breasts: El Shaddai in the Bible.” History of Religions 21, no. 3 (1982): 240–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062160.

Pocock, Machiavellian Moment, 30.

England, for example. Pocock, 360-71.

Rosenthal, Crown under Law, 160-61.

Rosenthal, 178-81.

Rosenthal, 89. See also Bretherton, Christ and the Common Life, 360.

Magna Carta was “a restorationist act, seeking to bind the king in the standard medieval ways,” according to Professor Jean Bethke Elshtain. Elshtain, Sovereignty, 66.

See, for instance, Romans 1:4.

See, for instance, Ephesians 1:13-14.

Elshtain, 119.

Bretherton, Resurrecting Democracy, 222.

Bretherton, 220-21.

Kreeft, Platonic Tradition, 70.

Elshtain, 98.

Colossians 1:15 KJV. See also 2 Corinthians 4:4; Colossians 3:10.

Matthew 25:40 NNAS.

Quoted in The Divine Dance: The Trinity and Your Transformation by Richard Rohr and Mike Morrell, 159.

Borg, 78.

Colossians 1:13 KJV.

I thought about drawing a circle, but even that presumed too much. My page is a silence.

Fascinating as always Bryce. I'm curious how this plays out in the thought of Jonathan Edwards. Edwards was one of the first colonial Americans to read Locke and Newton, and I'm sure this had impact on his theology in ways I have never had time to research. I've always veiwed Edwards as a transitional theologian from New England Puritanism toward New England Transcendentalism. His theology was stuck between the Soveriegn God and a more dynamic God, which is where his students moved towards. Thanks for an interesting read. I'd add that if you believe in Substitutionary Atonement, that God demands the blood sacrifice, the political julmp can be towards justifying a punitive justice system or defending torture in the name of fighting Communism, terrorism or whatever is deemed to be godless.