Dropping my appeal to heaven

The flag isn't a prayer; it's liberal declaration of war. Either way, though, it's a retreat.

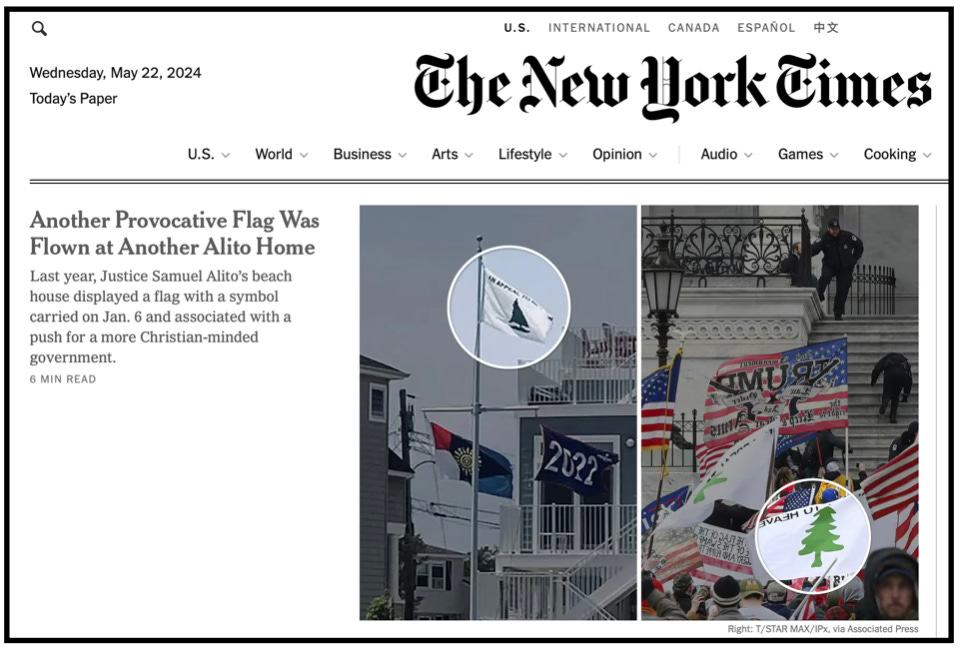

The New York Times reported three days ago that a Supreme Court justice flew the “Appeal to Heaven” flag, originally known as the Washington’s Cruisers flag, at his beach house last summer. The flag, the Times reported, was also flown prominently on January 6, 2021 among the rioters who broke into the Capitol.

The flag’s prominence among the rioters, the Times said, stems from its use since 2013 by people bent on turning the United States into a Christian nation. This movement assumes that the flag’s original “Appeal to Heaven” was a prayer to defend the colonies from the strong, oppressive British Empire. The flag’s updated “appeal,” or its prayer, would be for the furtherance of what the movement understands to be a biblical social agenda promulgated through the United States government and courts.

The Times article suggests that the Supreme Court justice in question must have known about these associations when he flew the flag. But I can’t know—and I really don’t care—what the justice thinks the flag signifies.

The flag as a liberal term of art

The Washington’s Cruisers flag is a variation of the Pine Tree flag, a simple jack of a green pine on a white field. The Massachusetts Navy pulled the idea for the flag's design from the more complicated Bunker Hill flag, which had a much smaller pine relegated to the flag's upper-left corner. Washington used the basic design of the Pine Tree flag for his own squadron of schooners in 1775, adding the words “Appeal to Heaven” or “An Appeal to Heaven” to it.

But “an appeal to heaven” isn’t a prayer. Instead, it’s a liberal term of art. It asserts the greatest right under liberal philosopher John Locke’s scheme of natural law rights—the right of revolution. The right of revolution is Locke’s enforcement mechanism in a case where a ruler attempts to alienate a subject or subjects from their inalienable right to life or liberty.1

Locke’s appeal process when lacking a common superior

Locke doesn’t find revolution desirable. However, Locke assumes the need for rulers, and a ruler’s oppression sometimes requires revolution to remove and replace the ruler. This revolution involves war.

For Locke, the state of war was like the state of nature: in both situations, individuals, groups, or nations are “without a common superior on earth with authority to judge between them.”2 The difference between a state of nature and a state of war is how the parties in such situations relate to each other. If they live together “according to reason,” then they are in a state of nature. But if one party uses “force, or the declared design of force upon the person of another,” then they are in a state of war.3

A state of war may exist between individuals or between nations, or it may exist between people and their rulers who exercise “a power the people never put into their hands.”4 Because there is no “common superior” to appeal to in such a state of war, the aggrieved party may appeal to heaven. That is, they may resist their rulers based on an unwritten law superior to the rulers' law:

. . . where the body of the people, or any single man, is deprived of their right, or is under the exercise of their power without right, and have no appeal on earth, there they have a liberty to appeal to heaven whenever they judge the cause of sufficient moment. And therefore, though the people cannot be judge, so as to have by the constitution of that society any superior power to determine and give effective sentence in the case, yet they have, by a law antecedent and paramount to all positive laws of men, reserved that ultimate determination to themselves, which belongs to all mankind, where there lies no appeal on earth, viz. to judge whether they have just cause to make their appeal to heaven.5

Such an appeal would be ineffective if heaven were bound by the rulers' laws, Locke here says. Instead, heaven judges the people's case “by a law antecedent and paramount to all positive laws of men” – natural law.

So our nation's first navy sailed under a flag that proclaimed our rights under natural law. “An appeal to heaven” was a liberal declaration of war.

I raised Locke’s “Appeal to Heaven” flag, too, then lowered it

Like the Supreme Court justice, I once displayed the Washington’s Cruisers flag. I designed a bumper sticker to look like the flag and stuck it on my Mercury Sable in 2011, two years before the flag’s recent history of being misappropriated. I liked the flag’s association with natural law and hoped natural law would one day serve as an interpretant between the positive laws advanced by Christian nationalists (the sign) and the Bible it claimed to implement (the signified). I still believe in natural law as one triadic understanding that exposes the dualistic foundations of nationalism.

But I’m no longer keen on the flag’s “appeal to heaven.” Locke’s argument in favor of violent revolution is undermined by its warrant: he assumes we need rulers. Jesus, on the other hand, told his alternative political community—the proleptic kingdom of God—not to rule over one another.6

Locke approves of neither a state of nature nor a state of war, and for Locke, the only way out of these states is to have a just ruler, a “superior” at the individual, national, or imperial level who can decide cases brought by litigants or warring factions. By taking on the public dirty work for us, the superior allows us to go about our private lives—marrying, making money, and buying and selling—in peace. Only when the judge becomes unjust, so to speak, does the litigant (for Locke, the individual or the entire polity) find grounds to appeal to heaven.

People must have sovereigns, Locke suggests, and his appeal process helps when things don’t go well. The process deals with extreme abuses by these earthly sovereigns.

But the Bible doesn’t teach us how to make human sovereignty work. Instead, it teaches us not to adopt any human sovereignty because sovereignty belongs only to God. Jesus got free of human sovereignty—the devil’s final temptation—just before he began announcing the alternative, the “kingdom of God.”7 Hannah Arendt would agree: “If men wish to be free, it is precisely sovereignty they must renounce.”8

Locke’s—and Paul’s—scalable notions of sovereignty

Paul, like Locke, clams that sovereignty is scalable. Locke states that his sovereignty principle applies to a tyrant’s oppression of a polity as readily as it does to civil court cases: “. . . where the body of the people, or any single man, is deprived of their right . . .” Likewise, when Paul remonstrates the Corinthian assembly members for going against each other before the civil magistrates, he moves easily back and forth between these civil court cases and the coming kingdom of God when the saints will judge the cosmos.9

But where Locke presupposes a need for sovereignty at both a local and national level, Paul calls on the Corinthian assemblies to abandon sovereignty until kingdom come: “So then do not judge anything before the proper time, till the Lord come . . .”10 This difference explains Paul’s horror at hearing that the Corinthian assembly members go to law against one another before the city’s civil authorities. In doing so, the assembly members are forsaking the kingdom of God and submitting to an earthly sovereign:

Instead, a brother obtains judgment over against a brother — and this before those lacking faith? In fact, then, it is already a total defeat on your part that you have lawsuits with one another.11

In suggesting how the matter might be resolved in the assembly, Paul suggests that wisdom, not sovereignty, would resolve the dispute.12 But in the (to Paul, absurd) case that no one in the assembly had wisdom, it would be better to “suffer injustice” from one another13 than to impatiently abandon the source of justice—God alone.

When the Corinthians seek out an earthly sovereign for justice, they relegate the church of God to the private realm. They cease to function as an alternative political community—as a forerunner of the kingdom of God.

Locke’s liberalism, much like Hobbes’s liberalism, privileges the private realm and assumes the need for earthly rulers. When those rulers oppress, Locke says, the people may appeal to heaven. That is, they may reenter the public realm and remove and replace the sovereign by force.

The Bible, on the other hand, privileges the public realm and looks forward to the fullness of this new age when God and his creation will inhabit the earth as public space. It also denies that, until that day, anyone but God should rule there.

The footnotes below refer to the full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Political philosopher Harry V. Jaffa defines Locke’s right of revolution adopted in the Declaration of Independence as “the right to use force against those who would deny us the security of our natural rights to life and liberty.” Jaffa, Crisis of the House Divided, 340.

Locke, Second Treatise, III.19.

Locke, III.19.

Locke, XIV.168.

Locke, XIV.168.

Matthew 20:25-28.

Matthew 3:8-11; Mark 1:12-15.

Arendt, Between Past and Future, 163.

1 Corinthians 6:1-11.

1 Corinthians 4:5 (Hart, New Testament, 325).

1 Corinthians 6:6-7 (Hart, 327).

1 Corinthians 6:5.

1 Corinthians 6:7 (Hart, 327).