Don't accept oppression. Overaccept it.

Creating with God's derivative justice

God kind of rolls with it. He doesn't, for instance, create the world from nothing. Instead, he finds the universe in chaos, and he creates with that chaos.1 This biblical creation account, thankfully, helps us separate our own creativity from the malaise of originality. Being creative pretty much means saying "yes, and . . ." to what's already there.

We don't like this. We want God to show up first. In translations, we mangle the Bible's opening syntax so that God creates from nothing: "In the beginning, God created . . ." But the Hebrew starts with the situation God addresses in creating—the situation of tohu wabohu, or chaos.2 We'd prefer, though, that God act independently of situation, that God have it all under control.

But control is chaos. Improv performers know this. Try to control a performance by coming up with something original—something out of nothing—and we’ll block the performance. Chaos ensues. Keith Johnstone, in what may be improv's most renowned book, links originality and chaos:

Ask people to give you an original idea and see the chaos it throws them into. If they said the first thing that came into their head, there'd be no problem.3

In other words, if you want some fun, just say "Yes, and . . ." to what the performance hands you. Chaos left to itself, as Johnstone suggests, is enervating and ultimately boring. But when God says, "Let there be light," he basically says to chaos, "You've got potential." That's startling, politically speaking, because chaos in the Bible—from Genesis to Revelation—represents empire and political oppression.4 Chaos really is control.

To say that "God is in control," then, is a little troubling since God doesn't cause chaos. Instead, God improvises with chaos. He accepts what he finds around him and puts it in the context of a bigger story. His voice, as in "let there be light," carries all the originality he needs. Us, too: we create public spaces when we stand up to chaos and speak.

Political chaos, of course, wants you voiceless; it doesn’t want you creating. If you doubt your voice, however, you might start with someone else's. (In composition classes, we call these voices “mentor texts.”) Sometimes, in his improvisation, even God uses someone else’s voice. When God challenges Pharaoh's Egyptian empire, which the Bible equates with chaos,5 he talks like Near-Eastern kings. Recall all those proclamations of "I am the Lord" in the Torah? It’s a derivative practice. Proclamations of "I am YHWH" simply appropriate the earlier "I am Mesha," "I am Yehawmilk," and "I am Azitawadda, the blessed of Ba'l," Professor Moshe David Cassuto points out:

. . . in accordance with its usual practice, the Torah employs the language of men, and commences the declaration in keeping with the opening formulae of the proclamations of human kings.6

I can hear YHWH now: "'I am Azitawadda'? Hey, I can do that."

Then with the plagues, God beats all the Egyptian deities at their own games and frees Israel.7 The Egyptian frog goddess and symbol of fertility?8 God gets into it. In a wink, he has frogs hopping in the Egyptians’ kitchens and ovens and—with a wink—their bedrooms and beds.9 God’s “yes, and . . .” often involves an element of satire.10

Irony, too. He demonstrates his justice by bringing down the mighty—and sometimes, as with Pharaoh’s chariots11 and Haman’s gallows,12 by turning the rulers’ own oppressive tools against them. When “the peoples hatch their futile plots,” after all, “He who sits in the heavens laughs, the Lord derides them . . .”13

You’ve heard of distributive justice? Procedural justice and restorative justice? All good. God’s also into derivative justice. (Derisive justice, too.)

God does improv. He creates with what's at hand. He finds mountains and makes them valleys, and vice versa.14 He finds Israel's neighboring kings oppressing their subjects with covenants. So in his derivative justice, God picks up the covenant practice, but he uses his covenants to bless. As Rabbi Everett Fox suggests, God borrows (purloins? filches? liberates?) cultural practices such as covenant-making to great effect:

. . . the stylistic pattern in [the institution of the Mosaic covenant, Exodus chapters 19-24] resembles what is found in Hittite treaty texts . . . [but] no other ancient society, so far as we know, conceived of the possibility that a god could "cut a covenant" with a people. This . . . fact leads to the observation that, for Israel, the true king was not earthly but divine.15

Even an Israelite innovation, then, is at the same time derivative: a god can cut covenant like a king! Regarding justice, God might also appropriate Tim Cook’s characterization of Apple: “not first, but best.”

Ever wonder, by the way, why God chooses to be known as a king at all? For one thing, his choice means that, for people serving God, the job's already taken, as Fox here suggests. Still, "kingdom of God" seems an odd fit for an outfit run without rulers, which is how Jesus describes God's politics.16 But ancient Israel was surrounded by powerful kingdoms and empires. Perhaps the “kingdom” in the kingdom of God is yet another instance of improv.

Israel's not the first oppressed nation to improvise with the political concepts of its oppressors. Subjects of kingdoms and empires—and refugees from them, too—often do that: they describe just societies by repurposing the language of oppression. They might, for instance, describe a political space without sovereignty, such as a democracy or a republic, as a millenarian kingdom. Sociologist James C. Scott finds this phenomenon among hill peoples who, the world over, have fled from the hegemonic lowlands for political freedom:

. . . virtually all the ideas that might legitimate authority beyond the level of a single village are on loan from the lowlands. Such ideas are, however, cast loose from their lowland moorings and are reformulated in the hills to serve local purposes. The term bricolage is particularly apt for this process, inasmuch as lowland fragments of cosmology, regalia, dress, architecture, and titles are rearranged and assembled into unique amalgams by prophets, healers, and ambitious chiefs. The fact that the symbolic raw materials may be imported from the lowlands does not prevent them from being confected by highland prophets into millenarian expectations that may be used to oppose lowland cultural and political hegemony.17

Hill people put this "bricloage" from "cultural and political hegemony" to new uses, ones that often oppose the oppressive ways of the fragments' sources. The villages, such as the ones in Jesus's Galilee, get together and improvise with this political bricolage.

And in their improv, these villagers neither accept nor block oppression. Instead, as theologian and theater buff Samuel Wells says, they "overaccept"; that is, they accept by using the oppressors’ fragments to suggest a larger and better story.18

Princess Di (speaking of royalty) gave us a famous example of overacceptance. A reporter asked her, a year before her divorce from the Prince of Wales, if she thought she'd ever become queen. Her response: "I'd like to be a queen . . . in people's hearts, but I don't see myself being queen of this country."19 Wells points out that Diana didn't block "the awkwardness of her predicament.” Instead, she overaccepted "the sadness of losing her throne" and placed herself "in a far more significant narrative" as the queen in people's hearts.20 She overaccepted “queen” to suggest a greater queendom.

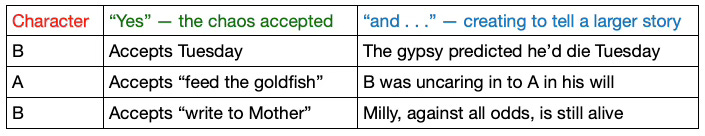

How does overaccepting work on the improv stage? Johnstone has his students practice overacceptance with a few rounds of "It's Tuesday," a game named after its invariable first line. Everything but this first line is contingent. Johnstone presents a possible progression among players A and B:

A: It's Tuesday.

B: No . . . it can't be . . . It's the day predicted for my death by the old gypsy! [Prolonged, agonizing death, ending with] Feed the goldfish.

A: That's all he ever thought about, that goldfish. . . . Fifty years' supply of ants' eggs, and what did he leave to me—not a penny. (Throws spectacular temper tantrum.) I shall write to Mother.

B: (Recovering) Your mother! You mean Milly is still alive?21

In this exercise, each player accepts the chaos of the other's lines. But the acceptance—the overacceptance—creatively makes something out of that chaos. The overacceptance begins to tell a new and larger story. Here’s a table with the specifics:

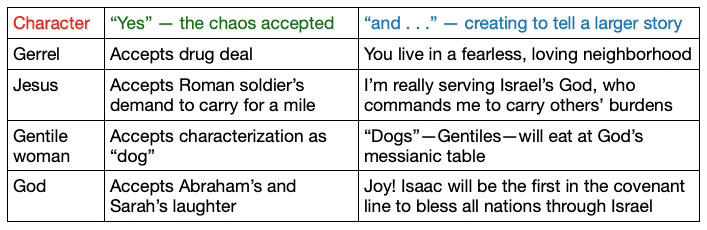

How might overaccepting work in public? Gerrel Jones, the founder of Renew Birmingham who made his home in the city's most violent neighborhood, may help us out. He was challenged by an elderly neighbor to do something about some drug dealers who recently had moved into a nearby rental. Gerrel knocked on their door and introduced himself as a neighbor. They all sat down on the front porch and started to get to know one another. Meanwhile, a customer approached, and one of the dealers on the porch tried waiving him off. Gerrel said, "No, don't worry about it." Gerrel witnessed the drug deal, but he never addressed it with the dealers.

Gerrel was signaling to the dealers that fear wouldn’t work in their new neighborhood. He didn't just accept their drug dealing; he overaccepted it, staying around to watch a deal and treating the dealers with love and respect. His overacceptance told a story beyond drug dealing, the story of a neighborhood where people respect one another and don't surrender their public space to criminals.

The dealers found themselves having to change or leave. They moved out within ten days. Gerrel explains:

People say, “That doesn't happen, oppressors never leave without the rebellion of the oppressed.” But what I’m talking about is a form of rebellion. It's the same form that Gandhi, King, and Jesus were talking about — it’s bringing positivity and love, but proactively.22

Jesus talks about it, and demonstrates it, too, in his parables about the kingdom. “Call my people a weed?” Jesus seems to say. Characterization accepted. But this prolific mustard seed becomes God's kingdom, Wells points out:

. . . the mustard plant is after all a weed, growing out of control where it is not wanted. This therefore is the way Jesus commends his revolution—not by accepting or blocking oppression, but by the surprise and abundance of a remarkable crop and by the uncontrollable spread of an infuriating weed.23

Jesus thereby says, "Yes, and . . ." to humanity, even to his enemies, just as God does when he mimics the earthly kings' language. Jesus says it also in his teachings involving the second cheek, the second garment, and the second mile, teachings in which Wells finds "a perfect embodiment of overaccepting."24 Theologian Warren Carter understands Jesus's strategy in these three "seconds" similarly:

Instead of cowering submission or violent retaliation, Jesus urges a nonviolent response to the superior’s slap, offering the other check to deflect the intended intimidation and demeaning [Matthew 5:39]. In 5:41 Jesus requires compliance to angaria, a custom whereby Rome requisitioned labor, transport (animals, ships), and lodging from subject people. But followers were to subvert imperial authority by carrying the soldier’s pack twice the distance, putting the soldier off-balance, in danger of being disciplined for overly harsh conduct.25

In improv terms, “cowering submission" is accepting the offer, and “violent retaliation" is blocking it. However, the essence of nonviolent resistance is (ironically, given the tactic’s name) overaccepting, particularly the creative use of oppressive fragments to suggest a larger story. Carrying a soldier's pack two miles instead of one? The larger story may be Messiah's law: "Carry each other's burdens."26 Going two miles thereby becomes the requisition of being requisitioned.

Jesus trains his disciples to enter into conversation with their enemies by expropriating their enemies' best material. Imagine the conversations over two miles that might come up between a Roman soldier and his kibitzing caddy.

Jesus also trains his disciples to recognize when they themselves may have become oppressors. Jesus appears to get a taste of his own overaccepting medicine when a Syrophoenician woman—a Gentile, on whom the Jews of Jesus's day look down—asks him to cast a demon out of her daughter. Jesus takes the role of the oppressor:

. . . the woman came and fell at his feet and cried, “Help me, sir.” Jesus replied, “It is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” “True, sir,” she answered, “and yet the dogs eat the scraps that fall from their master’s table.” Hearing this Jesus replied, “What faith you have! Let it be as you wish!” And from that moment her daughter was restored to health.27

Jesus calls her a dog, but the woman overaccepts the cruel characterization. By extending Jesus's metaphor, the woman participates in placing God's messianic table in the context of a greater banquet, one to which all humanity is invited. Whether Jesus was serious in his characterization or rather, as theologian G. B. Caird suggests, Jesus's words "were almost certainly spoken with a smile and a tone of voice which invited the woman's witty reply,"28 the Gentile woman’s overacceptance corroborates Jesus's remarks elsewhere suggesting that God's kingdom would be extended to all the world's peoples.29

In cutting covenant with Abraham, God, too, sets out to bless "all the nations of the earth"30—the same nations bound by their earthly kings' covenants. He announces the first fruit of that covenant by improvising—by refining his announcement to employ Sarah’s and Abraham’s responses to his announcement. That's how Isaac got his hame. I love how Frederick Buechner's rendition of what happens when God tells one-hundred-year-old Abraham and ninety-year-old Sarah that Sarah would finally have a child:

Then they laughed. One account says that Abraham laughed until he fell on his face, and the other account says that Sarah was the one who did it. She was hiding behind the door of their tent when the angel spoke, and it was her laughter that got them all going. According to Genesis, God intervened then and asked about Sarah's laughter, and Sarah was scared stiff and denied the whole thing. Then God said, "No, but you did laugh," and of course, he was right. Maybe the most interesting part of it all is that far from getting angry at them for laughing, God told them that when the baby was born he wanted them to name him Isaac, with in Hebrew means laughter. So you can say that God not only tolerated their laughter but blessed it and in a sense joined in it himself . . .31

By improvising, God joins in the fun. And Isaac, this impossible Laughter, is the first evidence of the nation God would use to set the other nations free.

Here’s a table summarizing some of the creation through overaccepting that we’ve seen so far:

As the table’s last line suggests, Isaac’s birth is all part of God's Grand Plan. But God’s plan, as Buechner’s account makes clear, doesn’t play out in fatalism. God’s plan plays out unexpectedly in improvisation. God's improv demonstrates that even the Grand Plan is contingent. We can stay at home with our blinds drawn and trust in some inexorable arc of the moral universe, or we can, like Martin King, improvise in public spaces.32

Both the seriousness and humor of God’s political improv point to the contingent nature of what the church calls the secular age, which begins in the book of Acts—the joy and even the fun that contingency affords us. In this “present evil age,” as Paul calls it,33 the age to come overaccepts the things of this age, breaking open “divisions between sacred and profane. If something is secular,” theologian Luke Bretherton points out,

it can be both sacred and profane, rather than sacred or profane, concerned with both the immanent and the transcendent, able to participate simultaneously in the penultimate and the ultimate. Secular time is thereby ambiguous and contingent.

God creates in this contingent secular time. The transcendent overaccepts the immanent. This age, Bretherton says, is where the fun starts:

. . . the secular, like pieces of Lego, is supposed to enable free and imaginative play. No one shape is definitive or determinative. Theologically, the secular is a time for the church to improvise forms of witness in response to the prior work of Christ and the Spirit, who are drawing creation into its eschatological fulfillment.34

To "improvise forms of witness" is to understand creation itself as improvisation—as the redemption of broken things that come to hand. Creation is redemption.

There's much to redeem. So much commentary today focuses on the tragic nature of our nation's politics. Other commentary focuses on how to keep ourselves sane during this unfolding tragedy, how to develop or continue certain life-giving hobbies and disciplines. Both of these forms of commentary, I think, are vital.

But they're also incomplete, as good tragedies might suggest. The best tragedies involve more than tragic events and intermissions with their respites in theater lobbies offering popcorn and bottled water. Tragedies also involve comic relief. Regarding Shakespeare’s Hamlet, for instance, Samuel Johnson notes that "the scenes are interchangeably diversified with merriment and solemnity."35 Why? Without the gravediggers' rustic logic, Polonius's pomposity, and Hamlet's wit, we'd never take on the tragedy's full weight. When I’ve had to process tragic circumstances, too, I've often found that laughter triggers my longed-for tears.

A tragedy's unrelieved tension, Shakespeare knew, "can lead to emotional fatigue or apathy," Sumneet Kaur and Himani Choudhary write.36 Political commentators, too, seem to fear that our nation's long and unrelenting movement away from republican government will lead to our fatigue or apathy (or both). Yoga or baking or even Orwell's roses may give me much-needed intermissions from relentless tragedy, but only my public overacceptance of the tragic forces will help me live out God’s command not to be overcome by evil. Paul explains:

“BUT IF YOUR ENEMY IS HUNGRY, FEED HIM; IF HE IS THIRSTY, GIVE HIM A DRINK; FOR IN SO DOING YOU WILL HEAP BURNING COALS ON HIS HEAD.” Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.37

Feeding our hungry enemies is both overacceptance and resistance.

Of course, like life and unlike Hamlet, improv isn't scripted. We do plan, but we plan in a community of interpretation practiced in an improvisational tradition. The Bible, too, which can be treated as a mere script, is an open-ended drama. Chaos returns and returns to the Bible's pages (e.g., Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Rome) as it does to our own public life. In response, we don’t read the Bible to find our lines. The Bible instead invites us, as Rowan Williams says, “to 'create' [ourselves] in finding a place within this drama—an improvisation in the theater workshop, but one that purports to be about a comprehensive truth affecting one's identity and future."38

Our lines—even, perhaps, our final lines—aren't fixed. Jesus suggests as much by telling us not to prepare for what might be our ultimate public performances:

"But when you are arrested, do not worry about what you are to say, for when the time comes, the words you need will be given you; it will not be you speaking, but the Spirit of your Father speaking in you."39

In such a situation, we probably won't speak famous last words. But if we improvise, we'll say "yes, and . . ." to our last moments as we have to our previous public moments. We'll place these last moments in a greater, redemptive story. And we'll speak what we will have become practiced in—our Father's own derivative justice.

A related post:

The above illustrations are generated from Bing Image Creator. The short footnotes below refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Regarding Genesis 1:2, Professor Robert Luyster finds that “In no case . . . do we find any mention of a creation ex nihilo. The cosmos pre-exists . . . Yahweh, even before undertaking any direct, creative action, is present and exercising a restraining influence upon the surging, watery chaos.” Luyster, “Wind and Water,” 257. Rabbi Everett Fox, in his translation of the Torah, notes that “Gen. 1 describes God’s bringing order out of chaos, not creation from nothingness.” Fox, Five Books of Moses, 13n2.

For more accurate translations of the Bible’s opening syntax, see Robert Alter’s The Hebrew Bible, Everett Fox’s The Five Books of Moses, and the Jewish Study Bible. This last work renders the Hebrew as “When God began to create heaven and earth—the earth being unformed and void, with darkness over the surface of the deep and a wind from God sweeping over the water—God said . . .” Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., The Jewish Study Bible, 2. ed (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014), 10.

Keith Johnstone, Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre (Taylor and Francis, 2012), 88.

Professor Terence E. Fretheim points out that a number of texts in the Hebrew Bible "identify the chaos monster with Pharaoh/Egypt.” (These texts include Ezekiel 29:3-5; 32:2-8; Psalm 87:4; and Isaiah 30:7.) In these texts, "Egypt is considered a historical embodiment of the forces of chaos, threatening to undo God's creation." Fretheim, “Reclamation of Creation,” 320. Most scholars of Revelation agree that Revelation’s version of Leviathan (the beast from the sea) represents the Roman Empire, and Revelation’s version of Behemoth (the best from the land), disguised as a lamb, are those forces in Asia Minor that support Rome’s imperial cult. Revelation 13:11. Michael J. Gorman, Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness: Following the Lamb into the New Creation ([S.l.]: Cascade Books, 2011), 167.

Professor Herbert G. May explains the connection of Egypt and chaos through an exegesis of Ezekiel 32, “in an oracle in which Pharaoh of Egypt is described as ‘like a dragon in the seas’ (vs. 2). . . . The king and land of Egypt are a manifestation of cosmic intransigent elements.” May, “Some Cosmic Connotations,” 265. See also the reference to Fretheim’s citations in footnote 4 above.

Cassuto, Commentary on Exodus, 76.

Cassuto says that many of the plagues accounted for in Exodus provide examples of “mockery at the expense of the Egyptian deities.” Cassuto, 97, 99.

Cassuto, 101.

Exodus 8:1-15.

Cassuto likes to point out the “mockery” and “satire” in the Bible’s exodus narrative. Cassuto, 99-100.

“He clogged their chariot wheels and made them drag along heavily, so that the Egyptians said, ‘It is the Lord fighting for Israel against Egypt; let us flee.’” Exodus 14:25 REB.

Esther 7:10.

Psalm 2:1-4 REB.

Isaiah 40:1-5.

Fox, 360. See also Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant.”

Luke 22:25-27.

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale Agrarian Studies Series (Yale University Press, 2009), 331.

Samuel Wells, Improvisation: The Drama of Christian Ethics (Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2018), 105-120.

The video of this portion of the interview, which you can access by clicking here, is striking.

Wells, 108.

Wells, 102. Italics in the original.

Sam Pressler, “Putting the ‘Neighbor’ Back in the Neighborhood,” Connective Tissue, April 10, 2025, https://connectivetissue.substack.com/p/putting-the-neighbor-back-in-the.

Wells, 115, summarizing the insights of John Dominic Crossan. This reading is corroborated by the mustard-seed parable’s parallel to Ezekiel’s parable of the cedar twig, which, representing Israel, “shall bring forth boughs and produce branches and grow into a noble cedar. Every bird of every feather shall take shelter under it, shelter in the shade of its boughs.” Ezekiel 17:22-24 JSB. The Jewish Study Bible comments that “God employs the allegory of the cedar to promise restoration” of Israel, then in exile. Berlin and Brettler, 1062n22-24.

Wells, 114.

Warren Carter, “Matthew and Empire,” in Empire in the New Testament, ed. Stanley E. Porter and Cynthia Long Westfall, McMaster New Testament Studies Series 10, H. H. Bingham Colloquium in New Testament, Eugene, Or (Pickwick Publications, 2011), 157.

Galatians 6:2, Wright, Kingdom New Testament, 389.

Matthew 15:21-28 REB.

George B. Caird and Lincoln D. Hurst, New Testament Theology, New ed (Clarendon Press, 1995), 395.

Wright, Jesus and the Victory, 308-316, citing the story of the Syrophoenician woman.

Genesis 18:18 NNAS.

Frederick Buechner, Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, 1st ed (Harper & Row, 1977), 52-53. My thanks to William Green for turning my attention to this delightful work.

Check out, for instance, the improvisational approach of the participants of the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott detailed in chapter seven (“Methods of the Opposition”) of King's book Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.

Galatians 1:4 NNAS.

Bretherton, Christ and the Common Life, 231.

Quoted in Sumneet Kaur and Himani Choudhary, “Locating the Elements of Comic Relief in Shakespeare’s Tragedy Hamlet,” International Journal of Trends in English Language and Literature 5, no. 1 (2024): 46–64.

Kaur and Choudhary, 47.

Romans 12:20-21 NNAS. The capitalized portion is a quote from Proverbs 25:21-22. (The New American Standard translation capitalizes words the authors purport to quote.)

Quoted in Wells, 45.

Matthew 10:19-20 REB.

Bryce Tolpen’s essay is a real achievement. By pairing Genesis’ *tohu wabohu* with Keith Johnstone’s improv lessons, he rescues creation from the tired ex nihilo debate and shows how God works with chaos rather than erasing it. “Derivative justice” is not second-rate but exactly how God repurposes empire’s fragments—mocking Pharaoh’s gods, improvising covenants, turning Roman coercion into a second mile walked in freedom.

The sources come fast—Cassuto, Johnstone, Scott, Wells—but the best moments slow down: Gerrel Jones on a Birmingham porch, Sarah and Abraham laughing, the Syrophoenician woman extending Jesus’ metaphor. These stories embody the overacceptance the essay commends.

I read with special appreciation the citation of Herbert May (a close family friend and a hugely significant influence on “seminary” education), whose work on Egypt and chaos still resonates. I also noticed the absence of David Bentley Hart, who has pressed hard against ex nihilo readings. Tolpen’s improvisational hermeneutic stands in fruitful tension with Hart’s metaphysical case.

If there’s a flaw, it’s the risk of overcrowding the stage. But the deeper accomplishment is clear: the essay holds tragedy and comedy together, insisting that political witness requires both lament and laughter.

Chaos may set the scene, but improv belongs to God.