Courage and identity

Introduction post 7 of 10

Good morning! Through biblical and modern examples, we explore the courage it often takes to look beyond private and professional stereotypes and to encounter the Other in public spaces. To access the other posts that make up the introduction to Political Devotions, click its subtitle’s post number: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Public space is demarcated in part by the courage—or sometimes the desperation—it takes to enter it. Four starving lepers create public space when they return to tell the good news: the sound of their approach caused the Syrian army that had been besieging Samaria to flee, leaving their well-stocked camp behind. Because the lepers risk disclosing themselves to their enemies, the Samarians can eat.1

Public space involves disclosure: we create public space, Arendt says, by “showing who one is, in disclosing and exposing one’s self.”2 In other words, we come out of hiding, even when this world’s rulers still can’t see us. By leaving Saul’s oppressive monarchy, David creates public space in a cave where “everyone who was in distress, and everyone who was in debt, and everyone who was discontented gathered to him.”3 When the distressed, debt-ridden, and discontented moved from the king’s murderous realm into a hidden cave, they came out of their private, politically hidden lives and disclosed themselves to one another.

Part of coming out of hiding is moving from what we are to who we really are. Public life, Arendt says, is the “disclosure of ‘who’ in contradistinction to ‘what’ somebody is—his qualities, gifts, talents, and shortcomings, which he may display or hide—is explicit in everything somebody says and does.”4 What somebody is, what role they play—a soldier, a tax collector, or a widow, say—doesn’t matter in public space. A Roman centurion turns out to have more faithfulness than anyone Jesus has met in Israel.5 A tax collector gives half of his possessions to the poor.6 A poor widow gives more to the temple’s treasury than everyone else combined.7 All these people show who they are in public. Jesus points out who they are because his listeners, unfamiliar with God’s kingdom, know only what these people are. His listeners know only these people’s qualities in the context of their private lives of work or family.

We experience others in our private lives of work and family, of course. But we encounter the Other in public. Jesus is the Other, the God hidden in the various whats—widows, lawyers, prisoners, tax collectors, harlots, soldiers, Pharisees, Sadducees, and aliens, such as the Samaritans. These categories dissolve in public space where people speak and act.

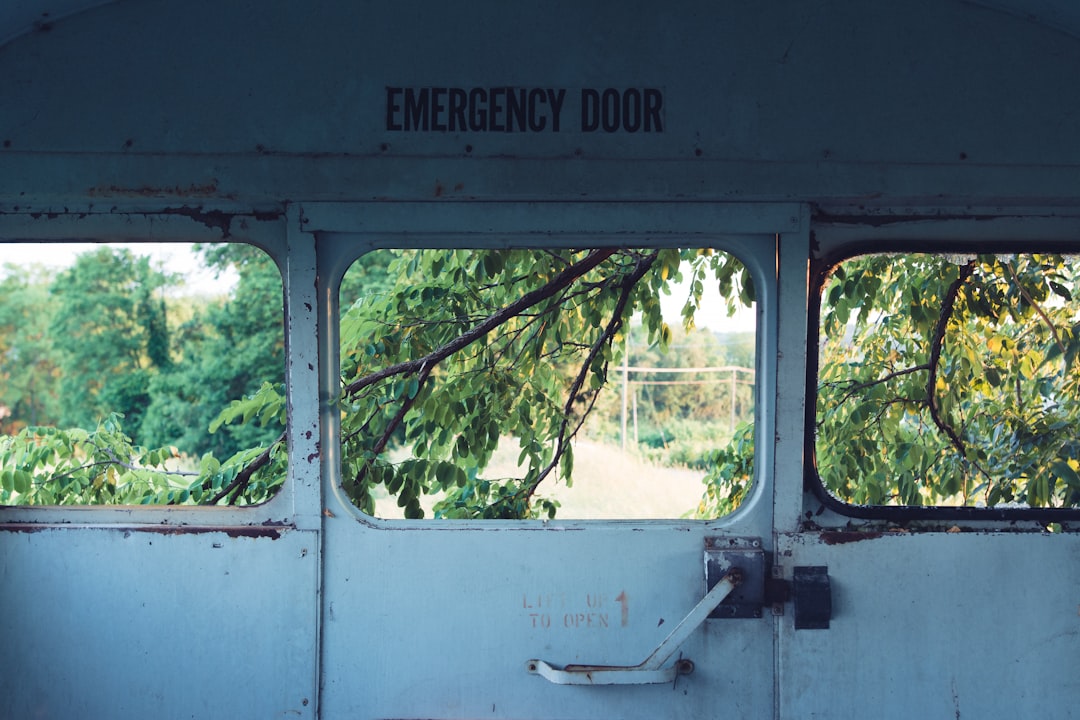

This contrast between the “what” of private and professional life and the “who” of public action is often ironic. Fifteen homeless people became the “keepers of Union Square,” where New York City’s greatest public forum blossomed for the first three weeks after the 2001 World Trade Center attacks—that is, until the authorities closed the forum.8 Poet René Char and other French civilians became members of the résistance who came, as Arendt puts it, “to constitute willy-nilly a public realm where . . . all relevant business in the affairs of the country was transacted in deed and word” during the Nazi occupation.9 A young mother caught a bus in my mother's hometown of Gloucester, Virginia, refused to surrender her seat to white passengers, got arrested, and helped to bring justice to interstate travel.10 Public transportation became public space.

Public space is as ironic as justice itself. Mary and Joseph are forced by an empire to travel to Joseph’s hometown where Mary would give birth to a rival king.11 She sang, before their trip, of public life’s ironies: "He has brought down rulers from their thrones, And has exalted those who were humble.”12

People create public space in many ways—too many ways to be fully catalogued. People create public space by engaging in passive resistance, mutual aid, public lamentation, street liturgy, hospitality to strangers, indigenous practices, community advocacy, anticipatory democracy, and even carnivals and revolutions. They create public space against a backdrop of public oppression, where a single person or party or gender or race or class dominates public life—or against a backdrop of public apathy, where a majority is content to live prosperous but unfulfilling private lives despite the injustices occurring just beyond their doors.

This is the seventh of ten posts that make up the book series’s introduction. Click here to read the next one.

2 Kings 6:24-7:20.

Arendt, Human Condition, 186

1 Samuel 22:2 NNAS.

Arendt, 179.

Matthew 8:5-13.

Luke 19:1-10.

Mark 12:41-44.

Rebecca Solnit calls Union Square “the city’s great public forum.” The forum’s organizer and central figure, Jordan Schuster, called these homeless people “the keepers of Union Square,” describing them as “ground maintaining, they were the support for this whole scene. And when I wasn’t there to help guide a decision about what was happening, they were the ones that were doing it and they did it brilliantly.” Solnit, Paradise Built in Hell, 200-3.

Arendt, Between Past and Future, 3.

The young mother was Irene Morgan. Arsenault, Freedom Riders, 11-18.

Luke 2:1-7; Matthew 1:18-2:12.

Luke 1:52 NNAS.