Be ye politically perfect

Jesus' call as path, not pathology

Why would anyone want to be perfect? I know, from hard experience, that following external rules to supposed perfection can limit me and wound people around me. This version of Christian perfection may find its perfect portrayal in Richard Rohr’s recent writing:

Any focus on perfection was an utterly false and illusory goal that made Christianity into a cult of innocence, whose adherents are so often full of blame and denial that they allow their fault to be projected onto others, unable to see similar failings in themselves.1

Despite Rohr’s reservations, though, Jesus thinks the rich young ruler wishes “to be perfect,” and he encourages him.2

Finding that a life dedicated to sinless perfection quickly turns pathological, many Christians have another, putatively Pauline way of dealing with Jesus’s injunction to “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.”3 For them, Jesus’s injunction is the Bible verse that creates a necessarily impossible standard, one that makes Paul’s formulation functional. In this reading, Jesus’s “be ye perfect” concentrates our guilt under the law wonderfully, permitting scripture to put us “all under sin, that the promise by faith of Jesus Christ might be given to them that believe.”4

But Jesus doesn’t get the theological memo. He doesn’t challenge the rich young ruler’s claim that he has always observed the commandments. Instead, Jesus responds to the ruler’s news by encouraging him to be perfect. Why?

Jesus’s “be ye perfect” has nothing to do with sinlessness or with obeying an external set of laws, even covenantal laws—including the Ten Commandments, several of which Jesus cites to the ruler.5 At the same time, Jesus’s “be ye perfect” is not an impossible path, though it sure looks life-altering.

Common misconceptions of biblical perfection as a sinless life, a religious pathology, or an effort in futility confuse two kinds of biblical covenants. They also ignore the political context of Jesus’s injunction to be perfect. But if we allow the Hebrew Bible and the politics of the disinherited back into the Gospels, Jesus’s call to “be perfect” makes perfect sense.

A brief, covenantal history of perfection

The ancient Near East practiced two kinds of covenants. One involves perfection, and the other doesn’t.

God enters into both kinds of covenants in the pages of the Hebrew Bible.6 The first kind, Rabbi Everett Fox says, is a “freewill granting of privileges,” and the second kind is “an agreement of mutual obligations between parties.” Hebrew examples of a “freewill granting” covenant include God’s covenants with Noah, Abraham, and David. The Bible’s chief example of a “mutual obligations” covenant, of course, is the Mosaic covenant.7

Rabbi Moshe Weinfeld makes the same distinction as Fox does between two ancient Near East covenant types, but he calls these types “grant” covenants and “treaty” covenants respectively. The differences between the two covenant types are stark. Overall, treaty covenants favor the greater party, but grant covenants bless the lesser:

While the “treaty” constitutes an obligation of the vassal to his master, the suzerain, the “grant” constitutes an obligation of the master to his servant. In the “grant” the curse is directed towards the one who will violate the rights of the king’s vassal, while in the treaty the curse is directed towards the vassal who will violate the rights of his king.8

As these differences suggest, the grant covenant is also a much more intimate arrangement than is the treaty covenant. So what would cause a king to enter into a grant covenant to bless a vassal? The vassal’s perfect devotion.

Ancient Near Eastern grant covenants required perfection, but not in the sense of never breaking a law or commandment that we associate with treaty covenants. Instead, grant-covenant perfection meant wholehearted devotion to the grantor.9 Ancient Near Eastern kings entered into grant covenants out of love in response to their vassals’ wholehearted devotion in service to those kings. In other words, covenantal perfection involved not legalism but relationship—specifically, the vassals’ devotion and acts consistent with devotion.

Assyrian kings would grant land or house (rulership) to a servant who walked after him “with his whole heart” or who served him “perfectly.”10 One Assyrian king named Ashurbanipal, for instance, entered into a grant covenant with his servant, Bulta, with language that might be familiar to readers of the Hebrew Bible. Weinfeld translates and annotates part of this grant:

“Baltya . . . whose heart is devoted (lit. is whole) to his master, served me (lit. stood before me) with truthfulness, acted perfectly (lit. walked in perfection) in my palace . . .”11

This parallel between faithfulness and perfection found in ancient Near Eastern grant covenants is found in the Bible, too, Weinfeld says:

The notion of “serving perfectly” found in the Assyrian grants is also verbally paralleled in the patriarchal and the Davidic traditions. Thus, the faithfulness of the patriarchs is expressed by “walk(ed) before me” . . .12

God uses this grant covenant language with Abraham in Genesis 17, for instance, connecting “walk before me” and perfection:

I am the Almighty God; walk before me, and be thou perfect. And I will make my covenant between me and thee, and will multiply thee exceedingly.13

God grants land to Abraham and house to David, finding Abraham “faithful” and finding in David a man “after my own heart.”14

This Hebrew conception of perfect finds its expression in teleios, the Greek word usually translated as “perfect” in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount and in Matthew’s account of Jesus’s interaction with the rich young ruler. The translators of Matthew’s Anchor Bible, W. F. Albright and C.S. Mann, regret the translation of the word as “perfect” because the English word

. . . carries implications of moral perfection to an extent which is not true of either the Greek or the Latin, and certainly not true of the Hebrew which lies behind the Greek. Translated as “perfect,” the word has Gnostic implications which are wholly foreign to the Gospel.

For that reason, Albright and Mann prefer to translate teleios as “true,” as in “true to God, true to the Covenant.”15

But because the Hebrew and Greek words meaning “true to the Covenant” in both the Old and New Testaments are almost always translated as “perfect” in English Bibles, I’d rather accept the English word “perfect” but reorient myself to a biblical understanding of “perfect.”

So when Jesus tells his listeners to be perfect, he is using grant covenant language, just as God does when he tells faithful Abraham to be perfect.

Both admonitions to “be perfect”—God’s admonition to Abraham, Jesus’s to his fellow villagers—are also parts of making grant covenants. Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount constitutes, after all, a “covenant renewal speech,” theologian Richard A. Horsley points out.16 Similarly, God’s direction to Abraham to “walk before me, and be thou perfect” is part of a covenant renewal speech, one that God makes twenty-four years after the first expression of his grant covenant with Abraham.17

Why Hebrews implies that Jesus wasn’t perfect

God’s grant covenant with Jesus himself, also known as the new testament,18 involves Jesus’s own perfection. This is why the book of Hebrews twice implies that Jesus isn’t perfect before his crucifixion:

For it was fitting for Him . . . to perfect the originator of their salvation through sufferings.19

Having in the days of his flesh, with a mighty outcry and tears, offered up both supplications and entreaties to the one who was able to save him from death, and having been heard on account of his reverence, he learned obedience from the things he suffered, even though he was a Son; and having been perfected he became a cause of salvation in the Age for all who are obedient to him . . .20

Jesus becomes perfect in this covenantal sense when he dies on the cross and rises from the dead. Just as Abraham isn’t perfect in a covenantal sense until he offers up his son Isaac as a sacrifice,21 so also Jesus isn’t perfect in a covenantal sense until he becomes the sacrifice that Isaac’s sacrifice foreshadows.

When ancient Near East kings would enter into a grant covenant with a subject, they would also adopt that subject and make him a son. The grant covenant would contain what Weinfeld calls “an adoption formula.” Weinfeld cites, for example, the “adoption imagery” of the king Hattušiliš I:

In this document which actually constitutes a testament we read: “Behold, I declared for you the young Labarna: He shall sit on the throne, I, the king, called him my son” . . .22

Jesus becomes a son of God in this covenantal sense at the same time that he becomes perfect—when he dies on the cross. In Romans, Paul views God’s resurrection of Jesus as God’s adoption of Jesus as Son in this covenantal sense:

This gospel God announced beforehand in sacred scriptures through his prophets. It is about his Son: on the human level he was a descendant of David, but on the level of the spirit—the Holy Spirit—he was proclaimed Son of God by an act of power that raised him from the dead: it is about Jesus Christ our Lord.23

The resurrection, Paul claims, is God’s declaration of his grant covenant with Jesus.

This ancient Near Eastern covenantal context helps make sense of some otherwise puzzling New Testament equations. It’s why Paul, for instance, associates a grant covenant declaration in Psalms with Jesus’s resurrection:

. . . God, who made the promise to the fathers, has fulfilled it for the children by raising Jesus from the dead, as indeed it stands written in the second Psalm: “You are my son; this day I have begotten you.”24

Paul claims that Jesus is “begotten” (made a son) on ”this day”—on the day of his resurrection. Peter on Pentecost also associates a grant covenant declaration in another Psalm with Jesus’s resurrection:

David, after all, did not ascend into the heavens. This is what he says: “The Lord said to my Lord, / Sit at my right hand, / Until I place your enemies / Underneath your feet.”25

Jesus’s resurrection and his contemporaneous covenant sonship, Paul and Peter maintain, establish God’s grant covenant to humanity through Jesus.

In contrast to Jesus’s grant covenant, the Israelites’ treaty covenant doesn’t lead to perfection. Hebrews tells us that perfection isn’t possible under the Mosaic covenant: continuing priestly and Levitical sacrifices, Hebrews tells us, can never ”make the comers thereunto perfect.”26

It’s interesting that Hebrews describes Jesus before his death as both sinless27 and as not yet perfect. Therefore, even if we succeed at becoming sinless—and good luck with that—we’d never thereby reach biblical perfection. No treaty covenant—no set of commandments, no matter how holy—can lead us toward perfection. But, Hebrews says, “the bringing in of a better hope” can.28

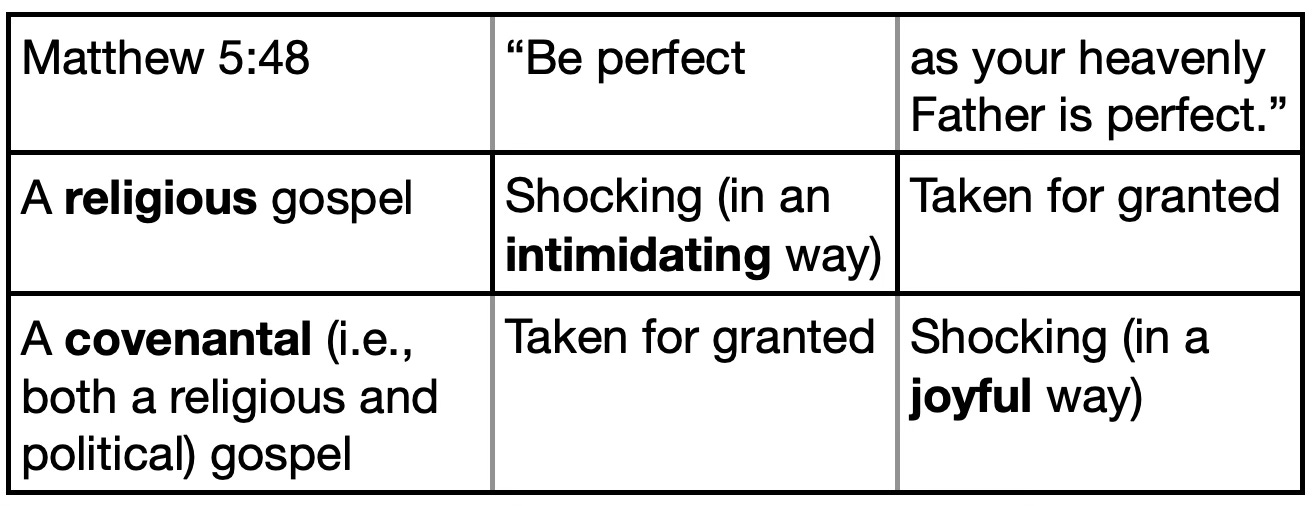

The shocking way that “be perfect” is shocking

Even after we absorb all of this covenant context, Jesus’s statement that “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” seems shocking. From an ancient Near East covenantal standpoint, though, the shock doesn’t come from the statement’s first clause but from its second. Regarding the first clause (“be perfect”), an ancient Near East king would always need to find his servant with a perfect heart toward him in order to enter into a grant covenant with her or him. No surprise there.

But the second clause (“just as your heavenly father is perfect”) is shocking because kings, as a condition for covenanting, didn’t have to have perfect hearts toward anyone. God, however, is as perfect—more perfect, one might say—in covenant as those with whom he enters grant covenants.

How is God perfect, then? Just as our perfection has little to do with being “without sin,”29 so also our heavenly Father’s perfection has little to do with his (by definition, I suppose) inability to sin. God’s perfection, in other words, doesn’t stem from his omnipotence or from his role as a lawgiver.

Instead, God’s perfection in covenant is of the same nature as any faithful servant’s perfection in covenant. God is love, of course, so he initiates. But he also responds with devotion as the recipient of a grant covenant would. Jesus pictures God’s perfection in covenant as a master hastening to become a servant:

Blessed are those slaves whom the master will find on the alert when he comes; truly I say to you, that he will prepare himself to serve, and have them recline at the table, and he will come up and serve them.30

God’s perfection in covenant, then, suggests an upside-down political world. In ancient Israel's neighboring nations, human kings ruled, and they initiated the most important covenants. But in biblical Israel, God rules, and he initiates the most important covenants. God demonstrates the nature of his rule by demonstrating both his weakness and his power in his grant covenant with Messiah.

Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection, then, become the revelation of God to the world in covenant. Taking us through another Pauline expression of God’s declaration-through-resurrection, this one in Philippians 2, theologian Michael Gorman points out that Jesus’s death and resurrection reveal God’s nature. After discussing the passage’s account of Jesus’s humility and obedience in crucifixion, Gorman focuses on that passage’s covenant language “therefore God raised him to the heights”:31

Thus the "therefore" of v. 9 does not signal that God has promoted Jesus to a new status, as if divinity (for a Jew) could be manufactured or gained by some act, however noble. Rather, it indicates that God has publicly vindicated and recognized Jesus' self-emptying and self-humbling as the display of true divinity that he already had . . .32

God’s declaration of a grant covenant with Jesus through Jesus’s resurrection, then, is a declaration of God’s own nature. Both God the Father and Jesus are perfect in covenant. That is, both the Father and the Son are both master and servant—and they are master because they are servant. Theologian John Howard Yoder puts it this way:

. . . what happened on the cross is a revelation of the shape of what God is, and of what God does, in the total drama of history. They affirm as a permanent pattern what in Jesus was a particular event. The eternal Word condescending to put himself at our mercy, the creative power behind the universe emptying itself, pouring out itself into the frail mold of humanity, has the same shape as Jesus.33

God isn’t of two minds, split between an all-powerful, militaristic God transformed in the New Testament into a Father, on the one hand, and a weak but loving God, pictured in the New Testament as a Son, on the other. Instead, God’s perfection in covenant and Jesus’s perfection in covenant demonstrate a single mind in which power isn’t the opposite of weakness but is, as Paul puts it, “perfected in weakness.”34

Paul himself doesn’t clam to be “already perfect,” he tells the Philippians, but he puts the covenant perfection he’s moving towards in terms of both power and weakness:

My one desire is to know Christ and the power of his resurrection, and to share his sufferings in growing conformity with his death, in hope of somehow attaining the resurrection from the dead. It is not that I have already achieved this. I have not yet reached perfection, but I press on, hoping to take hold of that for which Christ once took hold of me.35

Jesus’s politics, then, is God’s politics of power and weakness—God’s path to perfection in covenant.

To be perfect, be political like God

Like Jesus, we become perfect by following God’s example in covenant. That’s what “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect,” taken as a whole, means.

To make sense of how God’s perfection relates to ours, it’s worth looking at a similar passage, one from the Psalms, that also moves from God’s perfection to ours:

As for God, his way is perfect: the word of the LORD is tried: he is a buckler to all those that trust in him. For who is God save the LORD? or who is a rock save our God? It is God that girdeth me with strength, and maketh my way perfect.36

Here, God is “perfect” in a covenantal sense: his word is tried (reliable), and he is a shield to us and is trustworthy. God’s perfection in covenant, the passage suggests, leads us into a similar perfection—wholehearted devotion and faithfulness—in covenant: in the psalmist’s words, God “maketh my way perfect.”

But Jesus goes further. Jesus’s directive to “be perfect” suggests that our perfection isn’t simply a covenantal response to the Father’s perfection. It suggests also that our perfection will look substantially like the Father’s perfection. Examine just some of the lead-up to Jesus’s command to “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” in his Sermon on the Mount:

“You heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you: don’t use violence to resist evil! Instead, when someone hits you on the right cheek, turn the other one toward him. When someone wants to sue you and take your shirt, let him have your cloak, too. And when someone forces you to go one mile, go a second one with him. Give to anyone who asks you, and don’t refuse someone who wants to borrow from you.

“You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you: love your enemies! Pray for people who persecute you! That way, you’ll be children of your father in heaven! After all, he makes his sun rise on bad and good alike, and sends rain both on the upright and on the unjust. Look at it like this: if you love those who love you, do you expect a special reward? Even tax-collectors do that, don’t they? And if you only greet your own family, what’s so special about that? Even Gentiles do that, don’t they? Well then: you must be perfect, just as your heavenly father is perfect.”37

The Father’s perfection, this passage suggests, includes the passive resistance Jesus teaches through the two cheeks, the two shirts, and the two miles. It includes loving our neighbors and our enemies and not just our family and friends. God acts on his love for his enemies by giving them sunshine and rain, the same as he gives to “the upright.” This same God now abides in us through covenant, so we move toward his perfection by being God’s emissaries to our enemies.

God’s perfection is political, then, not only because it’s covenantal—i.e., not only because it’s based on an irreducibly political instrument called covenant. It’s political also because of the nature of that covenant. God’s covenant comes in power perfected in weakness. This perfection demonstrates God’s love for the entire world, including our neighbors and our enemies.

In Messiah, we walk in that same perfect devotion.

The rich young ruler’s reorientation

As told in Matthew, Jesus’s conversation with the rich young ruler is an exploration of this political (covenantal) perfection.

The politics begins with the young man’s profession—he’s a ruler of some kind38—and with his request. The ruler asks Jesus what good thing he needs to do in order to have life in the age to come. The political nature of this request is masked by most English translations, which tell us that the rich young ruler wants “eternal life.” But it’s a poor translation: the Bible never contemplates an eternity away from earth in heaven but a future age in which heaven comes to earth in the form of God’s just rule. Eternal life away from earth is just as platonic as perfection outside of a grant-covenant relationship.

The rich young ruler really wants “the life of the Age,” in David Bentley Hart’s translation,39 or “the life of the age to come,” in N.T. Wright’s.40 Wright’s commentary makes this distinction between “eternal life” and “life of the age to come” clear: the ruler’s question

. . . was, of course, the question of the kingdom: what must I do to have a share in the age to come, to be among those who are vindicated when YHWH acts decisively and becomes king? (It is not, that is to say, the medieval or modern question: what must I do to go to heaven when I die?)41

This distinction is vital for our purposes: the rich young ruler wants to participate in God’s rule on earth at the resurrection, when God acts fully as king and makes all things new. Perhaps the ruler wants to continue his political life on earth after the resurrection, to be part of the purchased people whom the living creatures and the elders later sing about in John’s vision:

“You have made them into a kingdom and priests to our God, and they will reign upon the earth.”42

The political aspect of the conversation between Jesus and the ruler is vital because it gives us more insight into Jesus’s bifurcated response to the ruler. Jesus’s first response is to cite several commandments under Moses’s treaty covenant. Jesus’s second response, though, is to tell something about what grant covenant perfection looks like.

The ruler’s response to Jesus’s recitation of commandments is, perhaps surprisingly, disappointment: “All these I have kept; what am I still lacking?” The ruler doesn’t understand Jesus’s statement as the end of the matter. He doesn’t say, for instance, “Great! I’ve kept them all. See you in the age to come!” The ruler seems to know that there is more to Jesus’s attractive life than what the ruler has experienced even with his (presumably) flawless treaty covenant scorecard.

Jesus’s reaction in Mark to the ruler’s “what am I still lacking?” intrigues me: “As Jesus looked at him, his heart warmed to him.”43 Perhaps Jesus knows the ruler has come to him for something more than self-justification. Perhaps Jesus’s love for the ruler is expressed in what follows—his grant-covenant invitation, which he hopes the ruler is ready to hear.

At all events, Jesus invites him:

“If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come and follow me.”44

Jesus asks the ruler to give up the authority and privilege that his riches afford him in exchange for a life of community with Jesus among the poor.45

Here’s Abraham leaving his home, family, and country. Here’s Jesus walking to Jerusalem and to his crucifixion. Here’s Paul, following after Jesus, counting all his resulting losses as shit.46 Here’s Abraham giving up his son and the promised heritage his son represents. Here’s God giving up his Son to demonstrate his love for his enemies and his power in weakness in the face of empire. Here’s grant-covenant perfection—God’s politics.

The short footnotes below refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Richard Rohr, The Tears of Things (Convergent, 2025), 145-46.

Matthew 19:20-21 REB.

Matthew 5:48 NNAS.

Galatians 3:22 KJV.

Matthew 19:18-19.

Israel didn’t invent covenant; its neighbors in the ancient Near East were covenanting before the Bible’s books began to be written. But Israel utilized its neighbors’ concept of covenant in a new way, according to Rabbi Everett Fox: “. . . no other ancient society, so far as we know, conceived of the possibility that a god could ‘cut a covenant’ with a people.” Fox, Five Books of Moses, 360.

Fox, Five Books of Moses, 360.

Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant,” 185.

Weinfeld, 185-86.

Weinfeld, 186.

Weinfeld, 185.

Weinfeld, 186.

Genesis 17:1-2 KJV.

Weinfeld, 185-87.

William Foxwell Albright and Christopher Stephen Mann, eds., Matthew: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, First Yale University Press impression, The Anchor Bible, volume 26 (Yale University Press, 2011), 232n21.

Horsley, You Shall Not Bow, 44.

Genesis 12:1-7; 17:1-22 KJV.

E.g., “This cup is the new testament in my blood . . .” Luke 22:20 KJV and 1 Corinthians 11:25 KJV.

Hebrews 2:10 NNAS.

Hebrews 5:7-9 (Hart, New Testament, 440).

Genesis 22. God’s final covenant renewal speech to Abraham, coming just after the angel stops Abraham from killing Isaac, is God’s most enthusiastic: “By Myself I have sworn, declares the LORD, because you have done this thing and have not withheld your son, your only son, indeed I will greatly bless you, and I will greatly multiply your seed as the stars of the heavens and as the sand, which is on the seashore; and your seed shall possess the gate of their enemies. And in your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed, because you have obeyed My voice.” Genesis 22:16-18 (NNAS).

Weinfeld, 190-91.

Romans 1:2-4 REB.

Acts 13:33 REB.

Acts 2:34-35 (Wright, Kingdom New Testament, 230-31).

Hebrews 10:1 KJV.

Hebrews 4:15. Admittedly, “without sin” in the context of Hebrews seems to focus on Jesus’s response to the temptation in Gethsemane to walk away from crucifixion, the obedience that would lead to his covenant perfection.

Hebrews 7:19 KJV.

Being “without sin” is a concept Jesus put to his fellow Jews as they threatened to stone an adulteress. John 8:7 KJV.

Luke 12:37 NNAS.

Philippians 2:9 REB.

Gorman, Inhabiting the Cruciform God, 30.

Quoted in Gorman, 34.

2 Corinthians 12:9 KJV. Stephen Fowl puts it this way: “In worlds such as ours and Paul's where power is manifested in self-assertion, acquisition, and domination, Christ reveals that God's power, indeed the triune nature, is made known to the world in the act of self-emptying.” Quoted in Gorman, 37.

Philippians 3:10-12 REB.

Psalm 18:30-32 KJV.

Matthew 5:38-48 (Wright, 9).

The word ruler (archōn) is pretty generic, so we can’t pin down what his specific title or function is. In his Luke Anchor Bible, Joseph A. Fitzmyer says the ruler might be a religious ruler and seems to be “a representative of pious legal observance—possibly a synagogue leader, possibly not.” It’s certainly not unusual, in Jesus’s day or in ours, for rulers to be rich. Fitzmyer, Gospel According to Luke X-XXIV, 1198n18.

Hart, New Testament, 38.

Wright, Kingdom New Testament, 39.

Wright, Jesus and the Victory, 301.

Revelation 5:10 (NNAS).

Mark 10:21 REB.

Matthew 19:21 REB.

Albright and Mann summarizes the encounter’s message: “The man who thinks that the life of the age-to-come can be earned by exact calculation is told to abandon all. In so doing he may learn in the community the lessons of humility.” Albright and Mann, 232n21.

Philippians 3:8.

I've been thinking about this a lot since I first read it some days ago. It seems to me that the English word "perfect" is part of the problem, as you've suggested. I went back to my Liddell&Scott and looked up teleios. While "perfect" is indeed one of the translations given, the Greek word also means "completeness", "fulfillment," "brought to accomplishment." These additional words feel a lot better to me in the context of the Gospels. The Greeks described an ideal sacrificial animal as "perfect" - meaning 'without blemish, whole, entire." They didn't mean "without sin," or "incapable of making mistakes." When Jesus spoke to the rich young man, doesn't it make more sense that he was saying, "follow me and move toward completion, toward fulfillment of all that you are truly meant to be" rather than "come back when you're perfect, because now you clearly aren't"? Translation can really trip us up, for centuries, and this has been true of the Bible for far too long. I was reminded of the passage where Jesus says, "I came that you might have life, and have it abundantly." The promise implied is for everyone, not just a chosen few who are "more perfect than others."

Thank you for this entire post and for the ways in which it has made me think deeply. Commitment, devotion, and a continual "turning toward" seem to me to be the operative calls to us, not an ideal of unattainable perfection that Jesus alone possesses. If that were true, then why come in a human body?

This is stunning work—deep, thoughtful, and courageous. I’m struck by how you recover the meaning of “perfection” not as sinless rule-following, but as wholehearted covenantal devotion. The contrast between treaty and grant covenants opens up so much clarity, and your grounding in ancient context makes the whole thing sing.

Your reading of Jesus’s call to be “perfect” as political, relational, and rooted in love rather than legalism is liberating—and timely. It’s theology with teeth and tenderness. Thanks for giving so much rigor, but also heart, to this conversation.