At several removes

Pilgrimages that deepen into political exile

As they were going along the road a man said to him, “I will follow you wherever you go.” Jesus answered, “Foxes have their holes and birds their roosts; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” — Luke 9:57-58 REB

Above: The Three Boats by Georges Braque

Teju Cole, a Nigerian-American writer, rounded a corner and witnessed a crime. He was in Malta, an island’s remove from Sicily, where he had earlier interviewed recent refugees. He had also broken down with grief beside beached boats, all reeking of human stench, that had carried other refugees across the Mediterranean. Among those boats may have been the one that had foundered, killing over seven hundred refugees, before being salvaged a year later by the Italian coast guard during Cole’s visit.1

The killing was in a cathedral. The corner Cole turned was created by a permanent partition just beyond the oratory. The partition, so placed, reinforced the immediacy Caravaggio achieved in The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, which Cole witnessed in situ. John is face down on the prison courtyard’s pavement. The executioner standing over him has cut John’s aorta, and John’s spurting blood pools beside his dead body. The executioner pulls up John’s hair with one hand, and with the other holds the viewer with his knife just before the beheading.2

My attempt in this essay’s opening to achieve something of Caravaggio’s immediacy is admittedly weak. I admit also to certain removes. The painting is now four hundred years old. The Gospels’ accounts of the killing are now two thousand years old. You can even fault me on the word “crime” since it’s the king who, at one remove, kills John.

Survivors share Herod’s remove. After each of Job’s servants tells his tragic news, the witness concludes with “I only am escaped alone to tell thee.”3 Having lost loved ones, I’ve read these servants’ confessions with some survivor’s guilt. Job’s poet, who I suppose survived something unspeakable to have written this poem, tells us the servants’ words (as well as Job’s) at yet another remove despite his unspeakable loss, or because of it.

Cole had gone to Italy and Malta during the summer of 2016 to witness. Cole’s pilgrimage traced the Italian cities Caravaggio had lived and painted in during the painter’s exile, which began in 1609 after he killed a man who had just bested him at tennis. Cole, an art historian and a journalist, “longed for the turmoil” he expected to feel standing before Caravaggio’s work. He also wanted to witness something of Italy’s refugee crisis.4

Above: The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Most Native American creation stories include migrations to new homelands as part of a people’s creation. The Hopi creation story, for instance, accounts for the nation’s four migrations around the North American continent, theologian and Native American activist Vine Deloria, Jr. says. Before setting out, the Hopi were “tested in the trauma of a world gone mad with power,” and their migrations amounted to a return “to the simple task of finding relatives in order that they might live in harmony with the rhythms of the land.” The Hopi eventually came to “the high mesa of the Southwest where,” Deloria says, “the giant canyon of light informed them of its antiquity.” Finding their connection with this seemingly inhospitable land, the Hopi were created and settled there.5

Most of us don’t think of ourselves as exiles. Most of us were never forced for political reasons to leave our homes. But Deloria, summarizing lessons from Native American creation stories, suggests that the experience of exile is common to humanity:

Our species, for ever so long, has believed that we are strangers in the world and many people have looked to the heavens for a sign that some time, in some place, they would no longer be strangers in the land. And so long as people felt incomplete and sought to find a home they were not really created.

Our exile, Deloria suggests, is our disconnection from the land around us, and we are “not really created” until we are connected with our proper land.6 Put more positively, our exile is a sign that our creation continues.

The Bible’s creation story fits the pattern Deloria discovers in Native American creation stories. The Torah begins in Genesis with creation and ends in Deuteronomy with warnings of exile. From the standpoint of Native American creation stories, then, the Torah may be considered one long creation story. Even the Bible’s creation story proper, as the Torah’s synecdoche, ends in a kind of exile. Adam and Eve are banished from the garden of Eden. Humanity starts homeless, and creation continues.

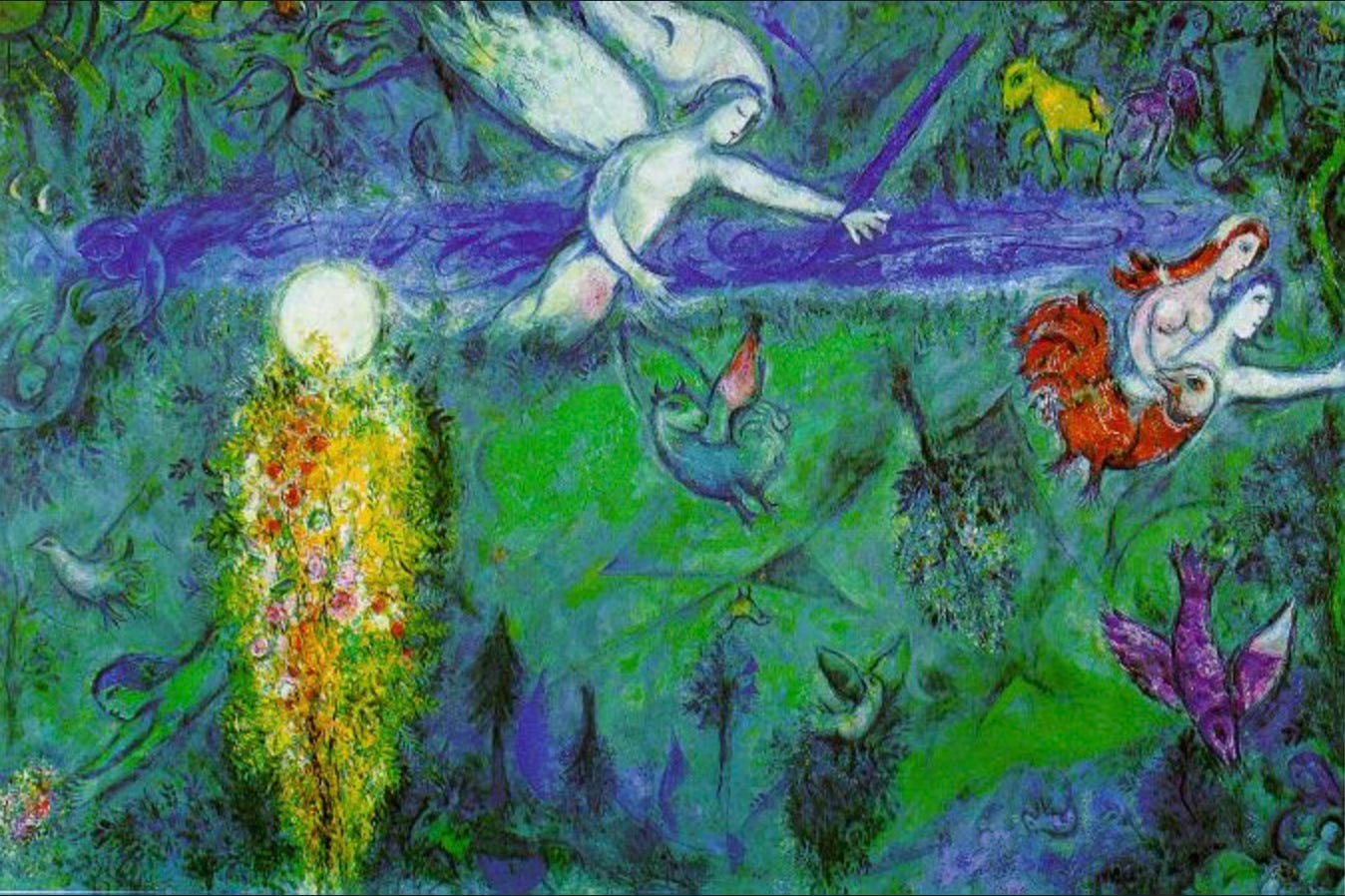

Above: Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise by Marc Chagall

Our public acts of pilgrimage affirm our political status as exiles. We confess, the book of Hebrews says, that we are “strangers and pilgrims,” or as the New American Standard puts it, “strangers and exiles,” on earth.7 As these translations suggest, “pilgrim” and “exile” are synonymous. Or they once were.

To moderns, an exile has fled trouble, but a pilgrim is on a spiritual journey. Safety breeds analogy, and sometimes allegory: Christianity’s status as Rome’s imperial religion lead to the Desert Fathers’ “green martyrdom.” Similarly, Christianity’s status as the West’s state religion lead to “personal pilgrimages”: witness John Bunyan’s allegorical and domesticated Pilgrim’s Progress, which Bunyan wrote despite his own status as a political prisoner. “Following Jesus,” as this week’s epigraph suggests, becomes too abstract without Jesus’s status as a wanted man. The Gospels report how he eluded arrest and death, sometimes by apparent miracle, sometimes by misdirection, sometimes by the exercise of forethought.8 Jesus’s homelessness wasn’t ascetic practice but political reality.

Pilgrims and exiles might yet kiss each other if Bunyan’s Celestial City, the goal of Christian’s pilgrimage, would itself hit the road. Instead of holding to its fixed point beyond the River of Death, the Celestial City might link up with New Jerusalem, an entire polity returning to earth from its exile in heaven,9 as a suitable traveling companion.

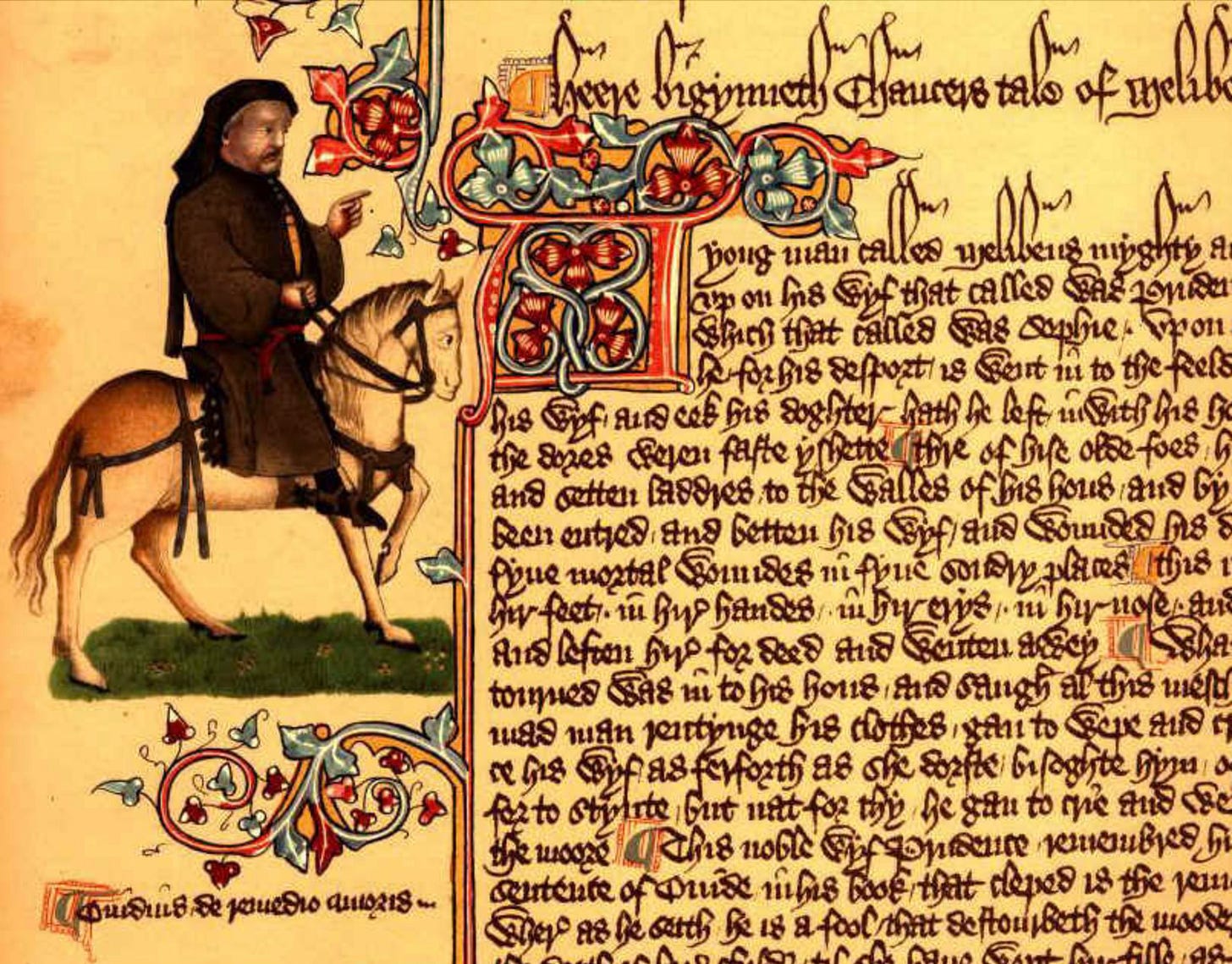

For a more biblical exilic community, one might put down Pilgrim’s Progress and pick up Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Admittedly, its narrator uncritically accepts some pilgrims’ misogyny and antisemitism. The narrator’s overall lack of discernment, though, allows him to find each of the pilgrims worthy in their own way; as Winthrop Wetherbee says, the narrator “must finally concede his inability to set his characters ‘in their degree,’ the place where they ‘stand’ in traditional social terms.”10 The narrator, in this sense, sees with exilic eyes: the journey strips all exiles of society’s demarcations. Back at home in society, Chaucer’s pilgrims—both the “gentles,” such as the Knight, the Squire, and the Franklin, and the “churls,” such as the Miller and the Reeve—would never abandon their stations to speak with one another candidly.11 But here they are, walking together away from home, telling stories and interpreting one another’s stories, creating a community of interpretation. Paul Strohm points out that Chaucer has created a model for a “mixed commonwealth”:

Chaucer has used the vehicle of a temporally and socially defined pilgrimage to inscribe a community of mixed discourse that models the possible harmony of a mixed state.12

This mixed commonwealth creates “true polyphony,” he says, because “its voices are never subject to dialectical resolution, but remain unmerged in ‘unceasing and irreconcilable quarrel.’”13 The characters’ tale-telling, Wetherbee says, is “what keeps the lives of the pilgrims open-ended . . .”14

The storytelling also keeps the pilgrims’ polity open-ended. Chaucer’s structure of storytelling at removes—his narrator, for instance, tells of each pilgrim narrating their own tale—creates mediation “as a positive social process,” Strohm says, “which does not simply restate intractable situations but restates them in terms more amenable to resolution.”15 These resolutions would be interpreted in examining opinions advanced toward further resolutions, consistent with the kingdom of God’s triadic community of interpretation.16

Above: Portrait of Chaucer as a Canterbury pilgrim, Ellesmere manuscript of The Canterbury Tales.

For centuries before the modern nation-state, pilgrims from many lands would journey to Rome or Mecca and discover a community beyond their homes and their vernacular languages. Benedict Anderson describes the experience as fostering a community beyond borders:

The Berber encountering the Malay before the Kaaba must, as it were, ask himself: “Why is this man doing what I am doing, uttering the same words that I am uttering, even though we can not talk to one another?” There is only one answer, once one has learnt it: “Because we . . . are Muslims.”

The religious pilgrimages, Anderson says, “are probably the most touching and grandiose journeys of the imagination . . .”17 On pilgrimage, we leave our private spaces, and in the act of witnessing, we create portable public space and the memory that sustains it. We witness, we testify, and we weigh others’ testimony. By practicing this citizenship without borders, we confess that we are exiles, and that our creation continues.

Above: Confrontation on the Bridge by Jacob Lawrence.

Not all migrations create community. The Western nations’ slave ships, the Trail of Tears, and the conditions of the boat people of the South China Sea and the Mediterranean, of course, wounded and destroyed communities. But we can build communities around exiles stripped of so much.

After his encounter with John the Baptist’s murder, Cole and a Gambian exile he met in Syracuse visited a church there to witness Caravaggio’s The Burial of St. Lucy together. They formed a brief community around the painting, the knife cut in Lucy’s neck evident to them both. It was the Muslim exile’s first visit to a church.18

Cole writes elsewhere of ways we might view communities that develop around the images of suffering people. One view advanced by Ariella Azoulay, he says, is the “participatory citizenship” surrounding the taking, publishing, and viewing of photographs. Cole summarizes the citizens in Azoulay’s “imaginative republic”:

Being the subject of photos, no less than taking photos or looking at photos, is one of a set of mutually reinforcing activities in which the participants are interdependent and complicit.

In what Cole calls a deterritorialized citizenship, a viewer’s participation replaces empathy and empathy’s tendency to survivor’s guilt, summarized by Cole’s “Why them and why not us?” This republic functions with less personal and more civic understandings of equality—Cole’s “What have we done . . . to create the conditions in which others, our fellow citizens, undergo these unspeakable experiences?”19

This latter question is the pilgrims’ inquiry as they retrace the exiles’ journey. On this pilgrimage to exile itself, we must distinguish among removes. That is, we must alternate among reflection, mediation, and the immediacy of action.

Discussion questions

1. What is the significance of witnessing at removes and as survivors?

2. What does Teju Cole’s trip—his focus on John’s execution, his tracking of both Caravaggio’s exile and the salvaged boat of refugees—testify about political status?

3. Are we exiles?

4. Cole describes his trip to Italy and Malta as a pilgrimage. How would a pilgrimage differ from a vacation for you? Where would you go on a pilgrimage, and what would be on your itinerary?

5. Consider Vine Deloria, Jr.’s explanation for the wanderings involved in most nations’ creation stories, that “so long as people felt incomplete and sought to find a home they were not really created.” Could our country’s destructive relationship to land—stripping, mining, farming, and developing it without regard to ecological consequences—be based in part on our failure to participate in our own creation?

6. The members of Ariella Azoulay’s “interdependent and complicit” community around a photograph of suffering resembles the members of Louise Rosenblatt’s community around a written text. Rosenblatt’s transactional theory of reading involved the reader’s experience as mediation to keep the dialectic among reader, text, and meaning from premature closure in truism or in what Paul Strohm calls “unmediated doctrine.”20 Ann E. Berthoff summarizes Rosenblatt’s theory: “Transaction, as Rosenblatt intends it, means that the relationship between the reader and what he reads is not dyadic, like stimulus-response, but is mediated by what he brings to what he reads, by what he presupposes and analyzes and conjectures and concludes about what is being said and what it might mean. Transaction is meant to keep the dialectic apparent and lively . . .”21 Does The Canterbury Tales make this kind of mediation explicit? If so, how? Can a community form around a pilgrimage, a photograph, or a text? How might each community function?

7. How does Strohm’s idea of The Canterbury Tales’ “mixed commonwealth” compare with Azoulay’s idea of photography’s “imaginative republic”?

8. How can a pilgrimage help to build an imaginative community around exiles, whose communities are often destroyed? How else could we follow the Torah’s command to love the exile as ourselves?22

More

A recent essay explores Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s call for the church to return to its exilic vocation, and it suggests how exiles might serve as models of citizenship in new forms of political communities:

Above: A Depiction of Dancing Mania, on the Pilgrimage of Epileptics to the Church at Molenbeek by Pieter Brueghel the Younger. The footnotes refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Cole, “After Caravaggio,” 17-23. (“After Caravaggio” appears in Cole’s 2021 book of essays Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time.)

Cole, 24-25.

Job 1:15-17 KJV.

Cole, 7.

Deloria, “Coming of the People,” 236.

Deloria, 236.

Hebrews 11:13 (KJV and NNAS, respectively).

Some examples include John 10:22-25; John 10:31-33; Luke 4:28-30; John 7:1-8: John 7:43-49; John 8:40.

“And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God . . .” Revelation 21:2 NNAS.

Wetherbee, “Introduction to Chaucer,” 516.

Wetherbee distinguishes between the tales’ “gentles” and “churls.” Wetherbee, 516-17.

Strohm, “Mixed Commonwealth,” 650.

Quoting Mikhail Bakhtin. Strohm, 648.

Wetherbee, 519.

Strohm, 650. Italics in the original.

For an overview of the church’s triadic community of interpretation, see The Problem of Christianity by American philosopher Josiah Royce.

Anderson, Imagined Communities, 54-55 (italics in the original).

Cole, 21-23.

Cole, “What Does It mean,” 103-4.

Strohm, 650.

Berthoff, “Democratic Practice, Pragmatic Vistas,” 129.

“When an alien resides with you in your land, you must not oppress him. He is to be treated as a native born among you. Love him as yourself, because you were aliens in Egypt. I am the Lord your God.” Leviticus 19:33-34 REB.

"...our exile is a sign that our creation continues."

P.S. - Simone Weil offers this:

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. But uprootedness is not the worst thing. What is horrible is to be uprooted without transformation.”

>Exile or dislocation can be a sign of ongoing transformation—a continuation of creation rather than its cessation.

Wonderful, Bryce. Thanks.

Bryce - I'm glad I like it, too. You surely elaborate your point, and, as always, make it from different angles. Thanks for your own footnotes. !