A politics stronger than death

Where the long debate between death and exile may lead us

In the early years of France’s New World settlements, French officials in Montreal invited their Iroquois neighbors to watch an execution. Five French trappers would die for their roles in killing two Iroquois warriors. Instead of being gratified, though, the Iroquois delegation was horrified. They pleaded with the French to spare at least three of the men. To the Iroquois, the death of five men seemed an unduly harsh retaliation for the death of two men. In response, the French commander tried lecturing his Iroquois guests about the merits of the European judicial principle of individual guilt, but to no avail.1

Over two hundred years after the Iroquois murder, another murder also highlighted differences between Western and indigenous notions of justice. This time, though, the murderer was an American Indian.2 In 1883, Crow Dog killed Spotted Tail, a BrÛlé Sioux chief who, in the words of Vine Deloria and Clifford Lytle, had “extended his chiefly privileges to include the wives of some of the traditional [tribal] leaders.” After the murder, the families of Crow Dog and Spotted Tail met and, in accordance with Sioux custom, negotiated compensation from Crow Dog to Spotted Tail’s family. The families were “eager to resolve their problems and avoid a continuing feud within the BrÛlés.” The whites living in that part of South Dakota, though, were horrified that Indian justice didn’t lead to Crow Dog’s execution. So Crow Dog was arrested, and a federal court jury convicted him of murder.

After Crow Dog’s conviction, things got better for him but worse for Native American justice. The United States Supreme Court overturned Crow Dog’s conviction on the grounds that Indian tribes had jurisdiction over their own criminal cases. The decision, however, only caused white public outrage to grow against BrÛlé Sioux principles of justice. In 1885, Congress, feeling the pressure of white opinion, passed the Major Crimes Act. The legislation and its later amendments stripped Indian nations of their jurisdiction over most felonies in their territories.3

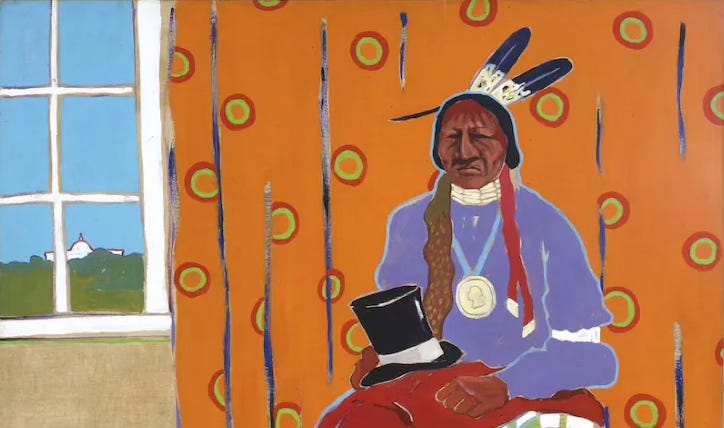

Above: detail of Washington Landscape with Peace Medal Indian (1976) by T. C. Cannon.

Unlike Western justice, which is oriented to the punishment of individuals, Native American justice is oriented to the restoration of community harmony. One can see this dichotomy in the two systems’ different notions of an ultimate punishment. In Euro-American collectivities that emphasize the individual over the community, the ultimate punishment is death. Native American justice, however, regarded banishment as the ultimate punishment, according to Deloria and Lytle:

Banishment, not execution, was regarded as the most serious punishment since an individual without a community or relatives literally did not exist as a human being for many groups.4

In collectives of individuals, the individual’s death brings oblivion. But in communities, the individual’s banishment brings oblivion.

Another killing—this one staged in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet—leads to a heated debate over death and banishment. The debate’s lead-up is well known: Romeo kills Juliet’s murderous cousin Tybalt and faces punishment for it. Earlier, after the play’s opening riot, the Prince warned the feuding families that further disturbance would result in execution. But despite his warning, the Prince decides not to execute Romeo. Instead, he banishes Romeo from Verona.

Romeo flees to Friar Lawrence, and the two argue about which of the two sentences is worse. Lawrence calls the Prince’s edict “dear mercy,” but Romeo thinks banishment is as bad as, or worse than, death. The argument hinges on their views of community. Romeo reasons that in a community, proximity is honor. “Carrion-flies” in Verona have more dignity than Romeo banished from Verona, he says, and banishment is more “mean”—more undignified—than death. Lawrence, though, holds a less place-based view.

One sees the characters’ different views of community in this exchange:

Friar Lawrence:

Hence from Verona art thou banished.

Be patient, for the world is broad and wide.

Romeo:

There is no world without Verona walls,

But purgatory, torture, hell itself.5

I must admit that during the first fifty or sixty times I taught Romeo and Juliet, I had the same reaction to Romeo’s arguments as does Lawrence: “O deadly sin, O rude unthankfulness!”6 But I’ve recently reassessed Romeo’s and Lawrence’s respective orientations. Romeo finds his identity in his community, but Friar Lawrence argues from a more Western viewpoint, characterizing communities as fungible. The world is full of communities, Lawrence suggests. Take your pick of places, pack your identity and toothbrush, and accept exile.

Above: All the Tired Horses in the Sun (1971-72) by T.C. Cannon

This Shakespearean debate reprises the drama in the Garden of Eden. In it, God acts much like Shakespeare’s Prince. He warns Adam and Eve that if they eat from the garden’s tree of the knowledge of good and bad, they’ll die. But, like the Prince, God ends up banishing the guilty parties instead.

Between these events, Eve recounts God’s warning to the serpent, and the serpent’s retort seems prescient: “You certainly will not die!”7 Friar Lawrence sees things from the serpent’s more Western, individualistic perspective, pointing out that the Prince’s earlier threat of death literally won’t come to pass.

Is the serpent’s retort the final word about this inconsistent God? Adam’s sin brought death with it, Paul says,8 but the couple’s banishment is also a synecdoche of Israel’s long exile.9 If the wages of sin is death, as Paul maintains, then those wages are paid in the specie of exile, as N.T. Wright points out: “Exile is the payment for sin, so forgiveness of sin means the end of exile.” To the New Testament writers’ way of thinking, the Messiah came to save us from both death and exile.10

Romeo would get the connection between God’s warning of death and the first couple’s exile. Romeo, after all, claims that “exile is death”:

Hence “banishèd” is “banished from the world,”

And world’s exile is death. Then “banishèd”

Is death mistermed. Calling death “banishèd,”

Thou cutt’st my head off with a golden ax

And smilest upon the stroke that murders me.11

Our Western society’s unwillingness to associate exile with death suggests its alignment with Friar Lawrence’s—and the serpent’s—side of the argument. We can avoid death, or at least deny death’s power, if we “become like God,” disassociating ourselves from our particular Eden.

In other words, we can avoid death if we become the earth’s overlords and thereby, so to speak, self-banish. Instead of developing community life, we live above communities and their places as self-sufficient individuals.

Deloria contrasts this Western avoidance of death with the acceptance of death among indigenous cultures. He attributes the difference to the communal orientation of indigenous cultures:

The singular aspect of Indian tribal religions was that almost universally they produced people unafraid of death. It was not simply the status of warrior in the tribal life that created a fearlessness of death. Rather the integrity of communal life did not create an artificial sense of personal identity that had to be protected and preserved at all costs.12

By contrast, Eden’s serpent wishes to protect and enhance this “artificial sense of personal identity” by offering the poisoned fruit of an individualized, supremacist worldview—to “become like God.”

Above: Woman's Dancing Feather (2012) by Michelle Possum Nungurrayi

All human cultures are tempted to manage the fear of death with some form of supremacy, Professor James K. Rowe says in his book Radical Mindfulness: Why Transforming Fear of Death is Politically Vital:

. . . the intense existential fear caused by the reality of death compels humans to psychologically buffer themselves with cultural constructions of supremacy that compensate for the overwhelming helplessness they feel in the face of finitude.13

Western cultures generally suppress death with “cultural constructions of supremacy,” Rowe says, but indigenous cultures generally fight these constructions by locating humanity within the natural environment and by making death part of everyday life. Offering an example, Rowe summarizes Coast Salish people’s integration of death into life:

The awareness of the dead that pervades everyday life for many Coast Salish people is, in effect, the opposite of death denial. Uncanny encounters with the ancestral dead are a part of real life. These encounters may be odd, or even frightening, but few dispute that spirits exist and have the power to influence the living.14

This kind of practice, Rowe says, amounts to a developed resource “for facing and transforming that fear” of death, one example of a resource that is “more likely to produce nonsupremacist and egalitarian worldviews.”15

Rowe examines how the fear of death, and the suppression of that fear through the denial of death, creates supremacist societies. Rowe doesn’t discuss, however, how such societies perpetuate themselves by exploiting the fear of death. The egalitarian Iroquois probably sensed this exploitation in the executions their French neighbors wanted them to enjoy.

The Roman Empire, to offer a more famous example, reserved the very public execution by crucifixion for political criminals. Rome used the spectacle of crucifixion, of course, to maintain its domination over its conquered peoples. It’s in this political context of crucifixion that we might consider the New Testament’s recognition, in the book of Hebrews, of how rulers exploit the fear of death and its claim in Hebrews that Jesus came to deliver us from this tool of subjection:

Since the children share in flesh and blood, he too shared in them, so that by dying he might break the power of him who had death at his command, that is, the devil, and might liberate those who all their life had been in servitude through fear of death.16

In reflecting on this passage, we should keep in mind that in the New Testament, the devil is a political as well as a religious figure. The devil tempts Jesus with earthly kingdoms—a supremacist form of government. In resisting this temptation, Jesus doesn’t challenge the devil’s claim to the world’s kingdoms. Instead, by means of his crucifixion, Jesus paradoxically defeats the dark powers behind rulers—”the cosmic powers and authorities”—associated with the devil.17

Jesus’s defeat of ”the cosmic powers and authorities” liberates us from those who, in association with those powers, have a monopoly of permissible violence. One sees this liberation play out in the book of Hebrews after the above “fear of death” passage. Hebrews cites people who are killed or otherwise persecuted, and in every case the book implies that the death or other persecution comes from political sources.18 Jesus’s victory in death, then, means (among other things) that we are liberated from regimes that use the fear of death to keep us from public freedom.

But do we exercise that liberation? Deloria, who had once been an Episcopal priest, asks why most Christians fear death:

If the Christian religion is a victory over death, why do Western peoples who have had the benefits of the Christian religion for two thousand years fear death?19

We find material to address Deloria’s question in Romeo and Juliet. The church, personified by Friar Lawrence, has too often participated in perpetuating the fear of death by serving hegemonic regimes. We find additional material to answer Deloria’s question in the Garden. The West, like the individualistic first couple, desires hegemony to keep death at bay and pays for its bargain with exile.

Jesus’s offer of freedom from the fear of death, though, raises a deeper question: is there an alternative politics, one grounded in something more substantial than hegemony and a monopoly of violence?

One alternative politics could be based on the kinship that makes exile in indigenous cultures tantamount to death. During the colonial and revolutionary eras, according to historian Richard White, many First Nations offered kinship to whites, and many whites accepted.20 Jesus, too, offers kinship with Israel to Gentiles. Jesus’s death, the writer of Ephesians says, ends the Gentiles’ exile from God’s people:

Thus you are no longer aliens in a foreign land, but fellow-citizens with God’s people, members of God’s household.21

We can learn about living in public freedom by studying and listening to communities, like those of many First Nations, that fear exile more than death.

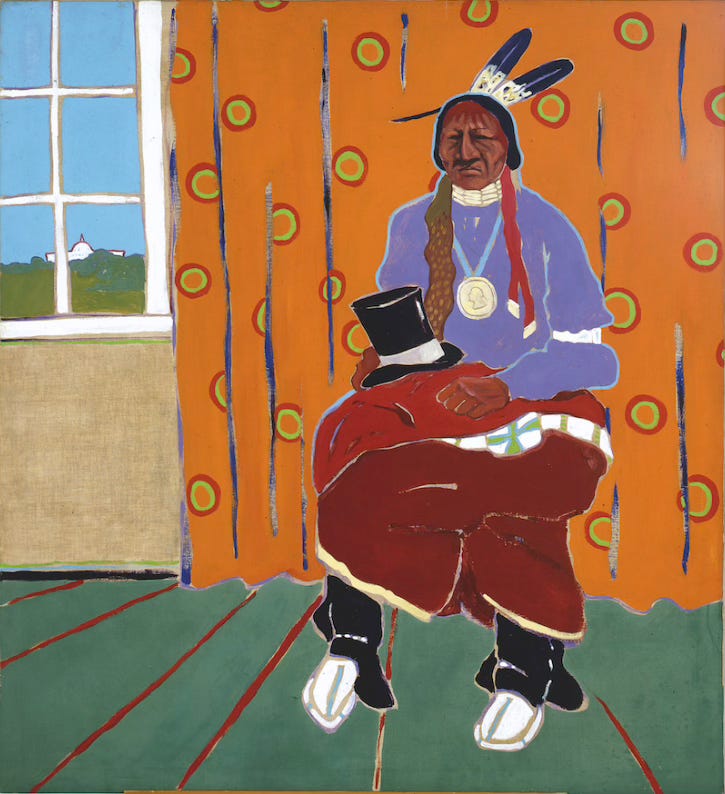

Above: Washington Landscape with Peace Medal Indian (1976) by T. C. Cannon. The short footnotes below refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Deloria and Lytle, American Indians, American Justice, 162.

For words referring to Native Americans, I take my cue from Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker, who use “Indian,” “Indigenous,” “Native American,” and “Native” interchangeably in their book “All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans. Dunbar-Ortiz and Gilio-Whitaker, ”All the Real Indians”, xi.

Deloria and Lytle, 169-70.

Deloria and Lytle, 162.

Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, 3.3.15-18.

Shakespeare, 3.3.25.

Genesis 3:4 NNAS.

Romans 5:12.

Wright, How God Became King, 66.

Wright, 71.

Shakespeare, 3.3.20-24.

Vine Deloria, Jr., God Is Red: A Native View of Religion, 3rd ed (Golden, Colo: Fulcrum Pub, 2003), 178.

James K. Rowe, Radical Mindfulness: Why Transforming Fear of Death Is Politically Vital (New York, NY: Routledge, 2024), 15-16.

Rowe, 106.

Rowe, 104-05.

Hebrews 2:14-15 REB.

Colossians 2:14-15 REB.

Hebrews 10:32-33; 11:35-38.

Deloria, Jr., 182.

Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815, 20th anniversary ed, Studies in North American Indian History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 366-412.

Ephesians 2:11-19 REB.

I like the idea, but I wanted to bring up the sakai incident as a possible addition.

Western politics, built on individual guilt and the primacy of death as punishment, blinds us to older traditions that saw banishment—and thus the loss of community—as the real end of a life. This piece shows how fear of death feeds supremacy, while indigenous justice begins from kinship. It’s a bracing reminder that our politics still misunderstands what people truly need. Thanks, Bryce.