Then [Jesus] said to his host, “When you are having guests for lunch or supper, do not invite your friends, your brothers or other relations, or your rich neighbours; they will only ask you back again and so you will be repaid. But when you give a party, ask the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind. That is the way to find happiness, because they have no means of repaying you. You will be repaid on the day when the righteous rise from the dead.” — Luke 14:12-14 REB

There are two First Baptist Churches in Macon, Georgia. The original First Baptist Church, established in 1826, counted both slaveowners and their slaves as its members, as was common in the antebellum South.1 But in 1845 the church created a second First Baptist Church for its slave membership. These two churches, First Baptist Church of Christ, which is still white, and First Baptist Church on New Street, which is still Black, have sat on nearly adjoining properties from 1887 through the present. For almost a century and a half, they had little contact.2

But in 2014, their pastors met. They soon decided to work together to try to heal their churches’ divisions. They started with a joint Easter egg roll, and soon they invited each other to potluck dinners. They began to share their lives and their perspectives, and they honored, in author Robert P. Jones’s words, “the act of observing and making space for” important ritual differences in their respective traditions.3

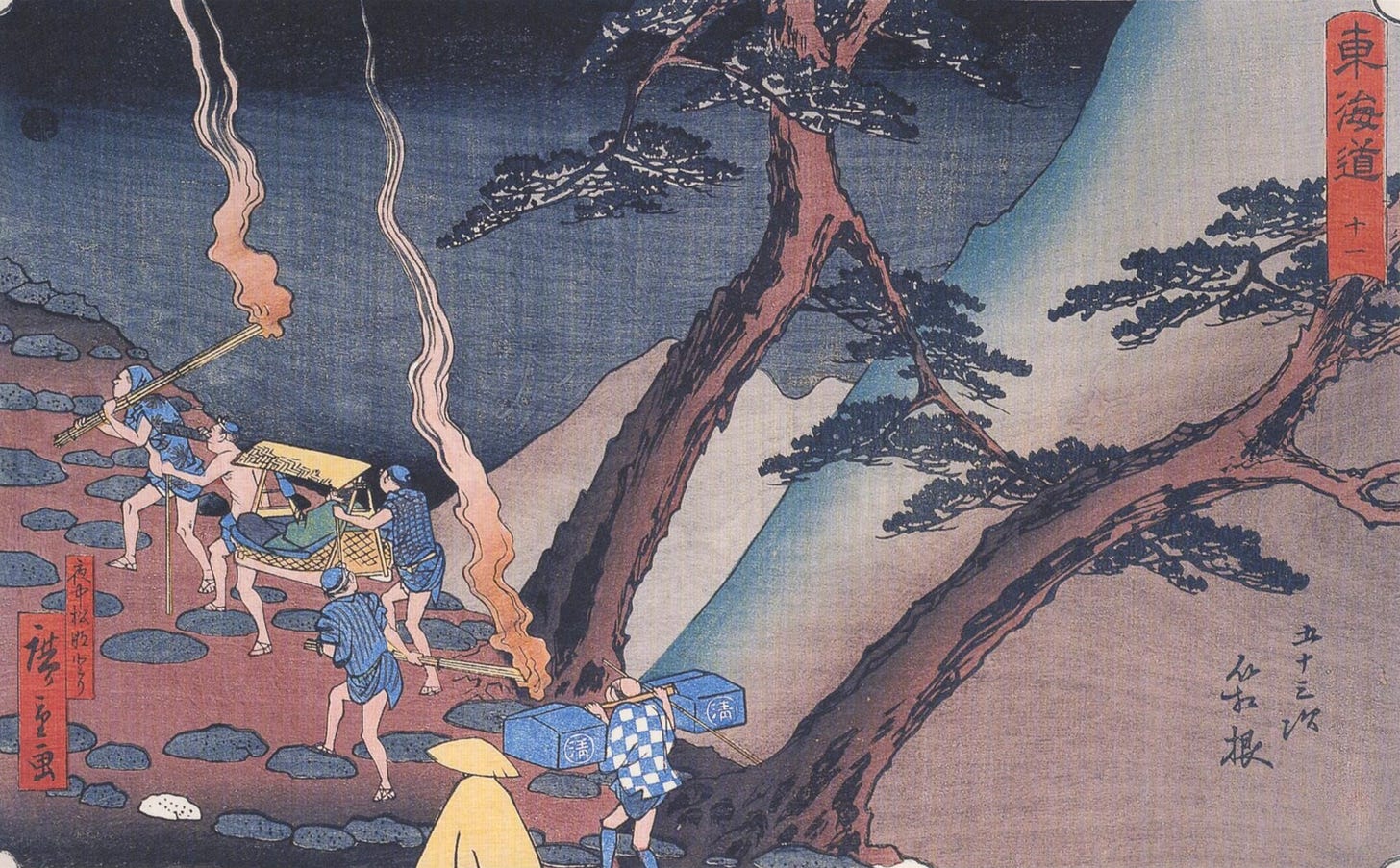

Above: Travelers on a Mountain Path at Night by Hiroshige.

A year later, at a joint communion service on Pentecost Sunday, the two churches entered into a written covenant committing themselves to racial justice and healing.4

Complications came, some unasked for and some sought. Three weeks after the covenant, in Charleston, South Carolina, a white supremacist gunned down nine Blacks at a church Bible study. Not long after that, historians found and published records indicating that FBC of Christ likely paid for its new building in 1855 by selling twenty members of FBC of New Street.

Some four years after those unsought-for complications, members from both churches traveled together to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, where they witnessed and responded to evidence of over 4,400 lynchings of Blacks.5 It was a tough trip.

In all this, the churches’ covenant shook, but it stuck.

Both churches attribute their covenant’s halting success to potato salad. When they were first getting to know each other, the churches didn’t swap pulpits or issue joint communiques. Instead, they relied more on “holiday potlucks, shared programs for children and youth, and service projects,” according to Jones.6 They had one another over for dinner a lot, and they demonstrated respect for one another’s cultural differences before they entered into covenant.7

Above: Poor Travelers at the Door of a Capuchin Convent near Vico, Bay of Naples by William Collins

Hospitality often precedes covenant. Abraham and Sarah demonstrate this progression, showing hospitality to the Lord and to two angels who show up at their tent in the guise of three strangers. When the strangers have eaten, the Lord affirms his covenant to Abraham and his seed, telling Abraham that Sarah will bear Isaac a year hence.8 Likewise, Rahab the harlot hides Joshua’s two spies in her Jericho home—a courageous act of hospitality—before they covenant to spare her and her family when Israel would attack Jericho.9

The writer of Hebrews may have been thinking of Abraham when he admonished us “to show hospitality to strangers, for by this some have entertained angels without knowing it.”10 Luke Bretherton, a professor of theological ethics, finds in this admonition the suggestion “that strangers may be the bearers of God’s presence to us.”

When Bretherton recounts the Bible’s angelic guests, though, he finds the hosts experiencing turbulence: Sarah’s laughing dismissal of God’s promise, Jacob’s wrestling with his identity and destiny, Mary’s incomprehension of God’s promise, and Zechariah’s unbelief, for instance, all come in the context of hosting angels. By extending hospitality to a stranger, the host opens themselves to the stranger’s gifts, some of which may have kept guest and host apart before then.11

In all four of these biblical examples, God’s kind of hospitality precedes the institution or elaboration of covenant, and that institution or elaboration involves the hosts’ displacement of sorts. Bretherton points out the loss of the familiar that we grieve in displacement:

The kinds of mutual transformation that just and loving hospitality involves necessarily entail loss, as the familiar and what counts as “home” are renegotiated. For new forms of common life to emerge, a process of grieving is necessary, as both guest and host emigrate from the familiar.12

This emigration and grief happened to Tim and Cathy, members of FBC on New Street and FBC of Christ, respectively, as they sat together and cried among the National Memorial’s columns for lynching victims:

The racial complexity of this moment . . . was thick for Tim. He later confessed to Cathy that he couldn’t help but think about what the evidence all around them demonstrated: that the simple physical proximity of a white woman and a black man was precisely the catalyst for the torture and murder of many a black man remembered on the columns suspended above them.13

For Tim and Cathy, hospitality to one another was slowly replacing distance, and it was painful.

Hospitality always acknowledges inequality. Guest and host never meet on equal terms. Hospitality “refuses the fantasy of neutral ground on which all may meet as equals,” Bretherton says. Instead, hospitality is “a way of framing how to forge mutual ground in a context where the space—be it geographic, cultural, or political—is already occupied and no neutral, uncontested place is available.” In other words, in an unjust setting, hospitality creates public space where no public space seems possible. Inherent in hospitality, then, is the movement from injustice to justice.

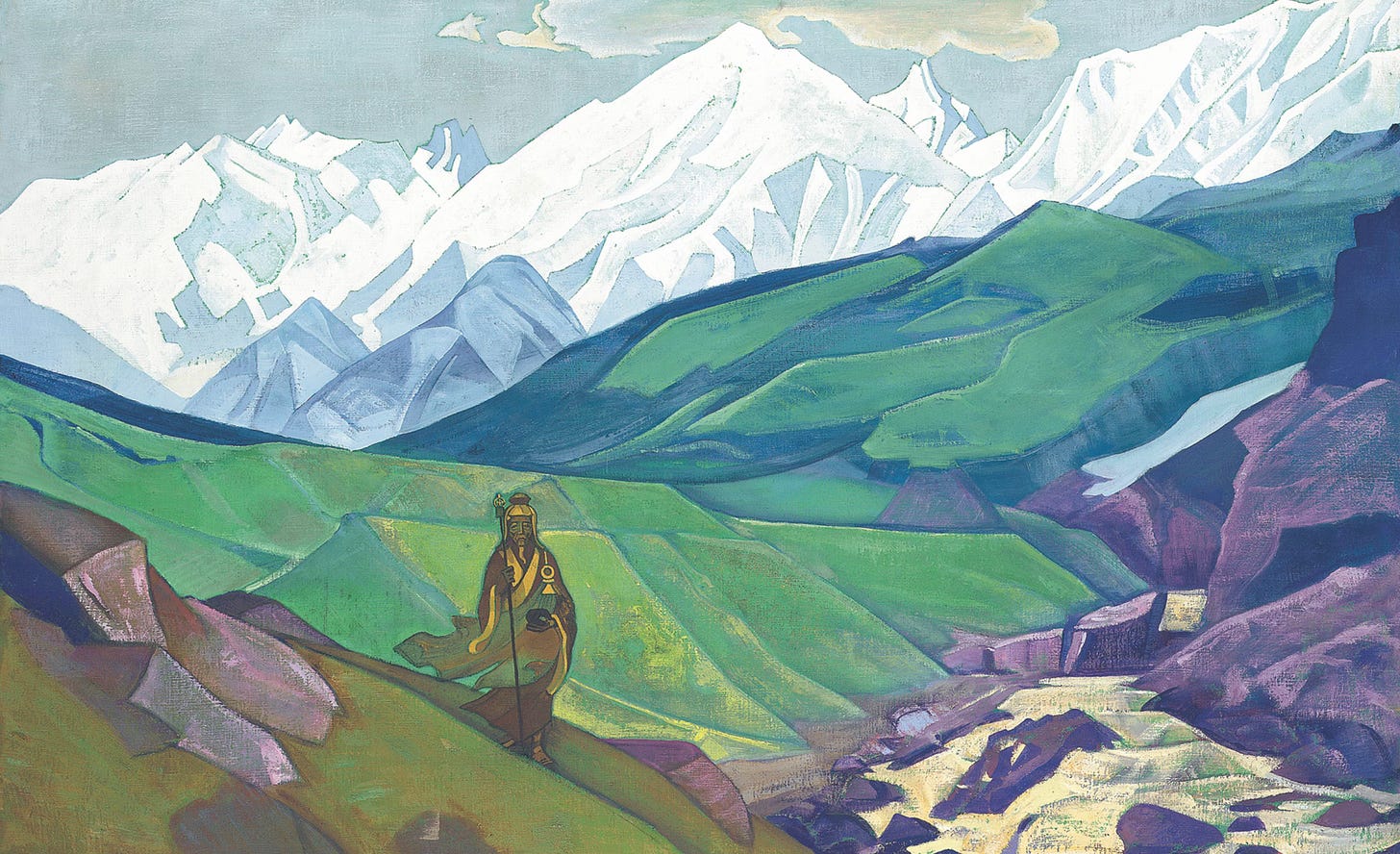

Above: Ienno-Guio-Dia — Friend of Travelers by Nicholas Roerich.

It’s helpful to compare hospitality to toleration, another means of interacting with strangers, but one with which moderns have far more experience:

With the advent of the modern state, public and mutual recognition between strangers becomes increasingly mediated and guaranteed through law and bureaucracy—with toleration replacing hospitality as the primary virtue governing relations with strangers.14

In our political and economic culture, we may limit our relations with strangers to mere toleration. The kind of hospitality Jesus describes to his host—the kind among strangers—is outside many Westerners’ experience. But this broader hospitality is political in the best sense of the word;15 as Bretherton says, hospitality among strangers is “a non state-centric form of relation.”16

Toleration needn’t be state-centric, either, of course. Toleration’s origins predate liberal government and what liberalism was, in part, intended to fix: a repeat of the religious conflict and wars of sixteenth and seventeenth century, the centuries when many liberal theorists, such as John Rawls, locate toleration’s origins.17 German philosopher Rainer Forst, for instance, contradicts “the widespread notion that toleration is a child of modernity.”18 Harvard professor Eric Nelson similarly argues against the “misconception . . . that toleration depends upon, and emerged out of, a conviction that church and state should remain fundamentally separate . . .”19 Both writers as well as other scholars locate toleration’s origins before modernity—at least the Western version of it—in Christianity itself.20

Toleration and hospitality generally address different political contexts. For toleration to work, the tolerant and the tolerated must be part of the same community. But while “toleration presumes a common life already in existence, hospitality does not, seeking as it does to generate one between strangers.”21

Toleration and hospitality also have different goals. Toleration seeks a greater good shared by both the tolerant and the tolerated—a good, such as common life, worth tolerating a perceived evil to achieve: “One tolerates the objectionable out of love for those goods that are a condition of human flourishing,” Bretherton says.22 The contrapositive is also true: if common life loses its value, then a polity’s toleration collapses. Hospitality, however, doesn’t seek only the maintenance of common life. It seeks new common life by finding God in the stranger. It seeks the kingdom of God in an unjust land.

Don’t get me wrong: toleration is biblical. Paul encourages disciples to tolerate one another’s views on meat eating and holidays23 and on meat offered to idols.24 But toleration merely maintains the churches’ unity. It doesn’t directly advance God’s reign of justice and peace.

Finally, unlike most modern instances of toleration, hospitality isn’t an abstraction that permits people to avoid one another. Hospitality as Jesus envisions it involves an “I-You” encounter, to employ Martin Buber’s concept, in which host and guest experience Messiah in each other while practicing the rites of inequality—rites that, despite themselves, give birth to public space. Jesus, the unknown Other and guest of his Emmaus disciples, suddenly becomes their host and becomes “known to them” at table when he breaks the bread. The disciples’ hospitality to the stranger is repaid with the revelation of the Messiah in the stranger.

The two Emmaus disciples don’t keep their encounter private. They immediately return to Jerusalem’s public life that they, with disappointment, had left earlier that day, and they compare their experiences with those of the other disciples.25

Hospitality between strangers, even Rahab’s secret hospitality, is never without public impact. The happiness that Jesus claims to be inherent in hospitality is rooted in God’s future public space, “the day when the righteous rise from the dead.” Hospitality is one of God’s chief means of experiencing resurrection’s new creation in this present evil age.

A liturgy for hosting strangers

Lord, we don't know these people well.

They're strangers. Or at least,

our society doesn't see them

as people we might host.

[Talk about in what sense your guests are strangers and in what sense they're not.]

But we’re strangers, too, and not just to our guests.

We were strangers to Israel's covenants of promise,26

and yet you invited us in.

Now we invite you in.

Fill the empty chair at our table,

the empty bed in our home,

the empty place in our hearts.

Fill the empty heart at the center of our community.

We've closed our doors to you for so long.

An oppressive empire made your parents travelers

when your mother carried you.27

Your hometown shut you and your family out

when you were born.28

You fled to Egypt as a refugee

when the king tried to kill you.29

When you were older,

proclaiming and living God's public life,

you still had no place to lay your head.30

We've invited our guests as we would invite you.

Help us prepare for our new friends' arrival

as part of preparing for your return.

Help us demonstrate to our own hearts

your living presence in the other—

your living presence as the other.

Keep us from congratulating ourselves,

from indoctrinating our guests,

and from participating in our society’s project

of alienating our guests from themselves.

Thank you for the gift of our guests.

May our merry hearts join our Martha hands.31

Help us wash our guests’ feet,

cleansing from their journey some of the disrespect

and even violence that our race or nation or tribe or gender

has practiced on theirs.

As we wash their feet,

we honor the journey that their feet have taken them,

and we associate ourselves with it.

Help us to learn something

of our new friends' perspectives.

Help us to give them time

to share in their way and in their time,

even if their way and their time

aren't what we might be used to.

Help us to give them place

to broaden our perspectives and enrich our lives.

Teach us something through them

that we would now think unimaginable.

Prepare our hearts to receive from our guests

something unexpected,

something troubling,

something not quickly or easily

resolved or understood.

Let our new friends find here

a stream to drink from on their way,

and more courage to hold their heads high.32

Help us to solicit and receive our guests’ critique

to make us better hosts. Help us also

to solicit and receive our guests’ blessing.

Help us sit with our guests’ gifts and their blessing

long after they have gone from us.

Bless and protect our guests as they come and as they go.

Bless their coming in and their going out

now and forevermore.33

Discussion questions

1. Do you understand the conflict in this devotion as one between the two First Baptist Churches’ history and their hospitality?

2. What is the relationship between hospitality and covenant? How do the cited biblical examples, and perhaps other examples, develop or contradict your thinking about that relationship?

3. As a practical matter, how can we follow the advice Jesus gives his host in this devotion’s epigraph? What challenges might we face before, during, or after such a meal?

4. Do you find the same significance in the inherent inequality of the guest-host relationship that Luke Bretherton finds?

5. Describe a time when you tolerated strangers, and describe a time when you hosted strangers or were hosted by them. How were the experiences the same, and how were they different?

6. In what sense is hosting a stranger a public thing? Can hosting a stranger amount to a form of justice?

Above: The Beggars by Honoré Daumier. The short footnotes below refer to full citations in the manuscript’s and this Substack’s bibliography.

Jones, White Too Long, 200-201.

Jones, 201.

Jones, 204.

Jones, 203-4.

Jones, 204–9.

Jones, 208.

The early-modern political philosopher Johannes Althusius, who based his federal system on the biblical notion of covenant, knew that a covenant wouldn’t work without personal relationships among the parties to the covenant. “For Althusius, as for all proper covenantal thinkers, covenants are not enough,” according to political scientist Daniel J. Elazar. “There must also be a covenantal dynamic, as symbolized by hesed [Hebrew for covenant love] and re’ut [Hebrew for neighborliness], which is ‘nourished, sustained, and conserved by public banquets, entertainments, and love feasts.’” Elazar, Covenant & Commonwealth, 318, quoting Althusius.

Genesis 18:1-15.

Joshua 2.

Hebrews 13:2 NNAS.

William Green makes a similar point from a more sociological and psychological perspective: “The stranger becomes a stand-in for something more intimate: the loss of place, identity, or control.” William Green, “Tip-Off #212 - Fear and Hospitality,” 2 + 2 = 5, June 19, 2025, https://williamgreen.substack.com/p/tip-off-212-fear-and-hospitality.

Bretherton, Christ and the Common Life, 282.

Jones, 209.

Bretherton, 273.

Bretherton, 272.

Bretherton, 273. Green points out that “Hospitality cannot be legislated, yet it can be nourished—locally and culturally, without waiting for Washington. Policy works best when it resonates in neighborhoods and reflects our own sense of self.” Green, “Fear and Hospitality.”

John Rawls, Political Liberalism, Expanded ed, Columbia Classics in Philosophy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), xxiv.

Rainer Forst, Toleration in Conflict: Past and Present, trans. Ciaran Cronin, First paperback edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 93.

Nelson, Hebrew Republic, 88.

See, for instance, Cary J. Nederman and John Christian Laursen, eds., Difference and Dissent: Theories of Toleration in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997), 1-16; Takashi Shogimen, “William of Ockham and Medieval Discourses on Toleration,” in Toleration in Comparative Perspective, ed. Anne Mocko and Vicki Spencer, Global Encounters Studies in Comparative Political Theory (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018), 3–22.

Bretherton, 258.

Bretherton, 267.

Romans 14:1-23.

1 Corinthians 8:1-12.

Luke 24:13-35.

Ephesians 2:12.

Luke 2:1-5.

Luke 2:6-7.

Matthew 2:13-15.

Matthew 8:19-20.

Luke 10:38-42.

Psalm 110:7.

Psalm 121:8 REB.

Bryce,

Your piece sings in three registers at once—story, theology, and ritual—and the harmony is strong. The Macon churches’ slow-motion reconciliation, down to the “potato salad diplomacy,” makes hospitality feel tangible rather than aspirational.

The way you move from that concrete narrative to the biblical pattern—Abraham’s visitors, Rahab’s spies, Emmaus’s stranger-turned-host—lets the reader feel the scriptural current running beneath civic practice. Your claim that covenant is impossible without prior table-fellowship is persuasive and refreshingly un-abstract.

Visually, the curation is pitch-perfect. Hiroshige’s moonlit travelers, Collins’s hungry pilgrims, Roerich’s watchful guardian, and Daumier’s exhausted beggars widen the lens from Georgia to the world; each canvas underlines your thesis that the stranger is always already on our doorstep.

On the other hand, the essay’s strongest provocation—hospitality as “political upgrade” over toleration—deserves one more turn of the screw. You note that genuine hospitality “refuses the fantasy of neutral ground” and therefore begins in inequality. Might that very asymmetry risk re-inscribing the power gaps the practice hopes to heal? In other words: when does hospitality slide into paternalism, and how might a liturgy guard against that?

A related question: the piece brilliantly shows how hosts are transformed, sometimes painfully, by guests. Yet the liturgy’s petitions still center the host’s agency (“Help us prepare…”). Would a reciprocal stanza—inviting the guest’s blessing or critique—further embody the mutuality you praise?

Finally, your toleration-versus-hospitality contrast is sharp, but it leans heavily on Bretherton. An aside engaging liberal defenders of toleration (say, Rawls or Martha Nussbaum) could sharpen the edge and reassure skeptical secular readers that hospitality isn’t merely a sectarian luxury.

These are trims, not overhauls. As it stands, the essay offers liturgical language sturdy enough for Sunday yet supple enough for city hall. Thank you for gifting us both a theology we can chew on and a table prayer we can pray.

In one of those odd convergences, I was thinking about what to write next about the devastating political moment in which we find ourselves, and "hospitality" seemed to rise to the top of my consciousness. Then I opened Substack and found this piece of yours. I appreciate so much what you say here and the argument you develop. Of particular relevance to what I hope to write, myself, is the point about toleration being quite distinct from hospitality. For many, including a lot of liberal Democrats, toleration is the easy way to say and believe they're "doing it" when actually they aren't moving their own hearts very far, aren't risking their own comfort, and -- even more importantly -- aren't actively doing things that can bring either "the Kingdom of God" or "a more perfect Union" closer. We must first open ourselves to an I-Thou encounter, and then both model and open paths for our families, institutions, and communities to follow. Thanks very much for writing this, and I hope it would be OK to quote a few bits from your essay when I write something.